In February [2017] I will be boarding a plane for Manila. It will take me 24 hours airport to airport, and that will feel like a long time. I will probably complain about how tired I am, or how small airline seats have become. Both will be true.

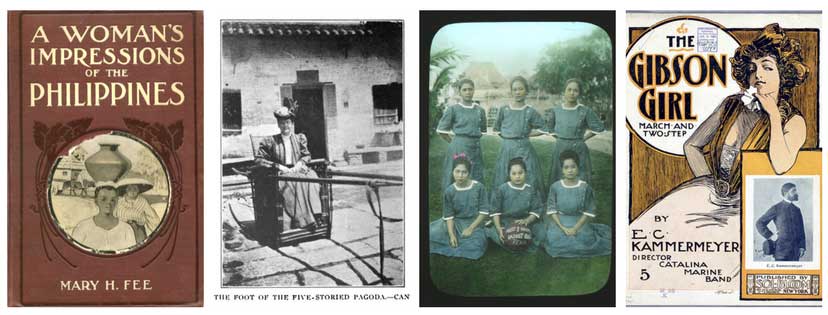

But my Edwardian sisters—known as “Gibson girls” after popular illustrator Charles Dana Gibson—would be shocked by how spoiled I am. For them, a trip from Boston to the Philippines would have taken seven weeks. And they thought themselves lucky, since the 1869 opening of the Suez Canal had cut the trip in half. Their bargain ticket would have cost $120 in 1900—the equivalent of almost $3500 today. My ticket cost around $800.

I also have another advantage: knowledge. I know what the Philippines are like. Things may have changed in the last five years, as things do, but generally I know what I will find. But my three Gibson girls featured here—Mary Fee, Annabelle Kent, and Rebecca Parrish, M.D.—did not. These women either had no information or bad information about the Philippines. (For example, a segregationist United States senator from Virginia claimed that “there are spotted people there, and, what I have never heard of in any other country, there are striped people there with zebra signs upon them.” Senator Daniel thought this ludicrous racist drivel important enough to pass along in the middle of a government hearing—and he was what passed for an anti-imperialist back then.)

If travel to the Philippines was long, expensive, and potentially dangerous, why did women like Fee, Kent, and Parrish do it? Their reasons probably varied. Fee, a teacher, may have gone for the good salary; Kent wanted to prove that she could travel the globe alone; and Parrish was a medical missionary whose faith led her to the islands. But there is one thing all three women had in common: they were more adventurous than the average man of their day. And they were probably more intrepid than me.

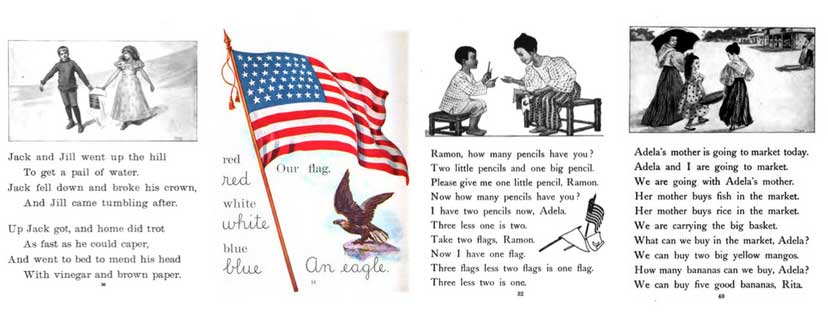

Let’s start with Mary Fee, principal of the Philippine School of Arts and Trades in Roxas City. Fee was one of the first teachers sent by the U.S. Government to establish a secular, coeducational, public school system throughout the Philippines. The Thomasites, as they were called, were sent all over the islands with their Baldwin Primers to read lessons on snow, apples, and George Washington—and none of the students knew what the heck they were talking about. Mary Fee realized that if she was going to teach her students to read and write in English—and, admittedly, that is a colonial enterprise she did not question but we should—then she needed new books.

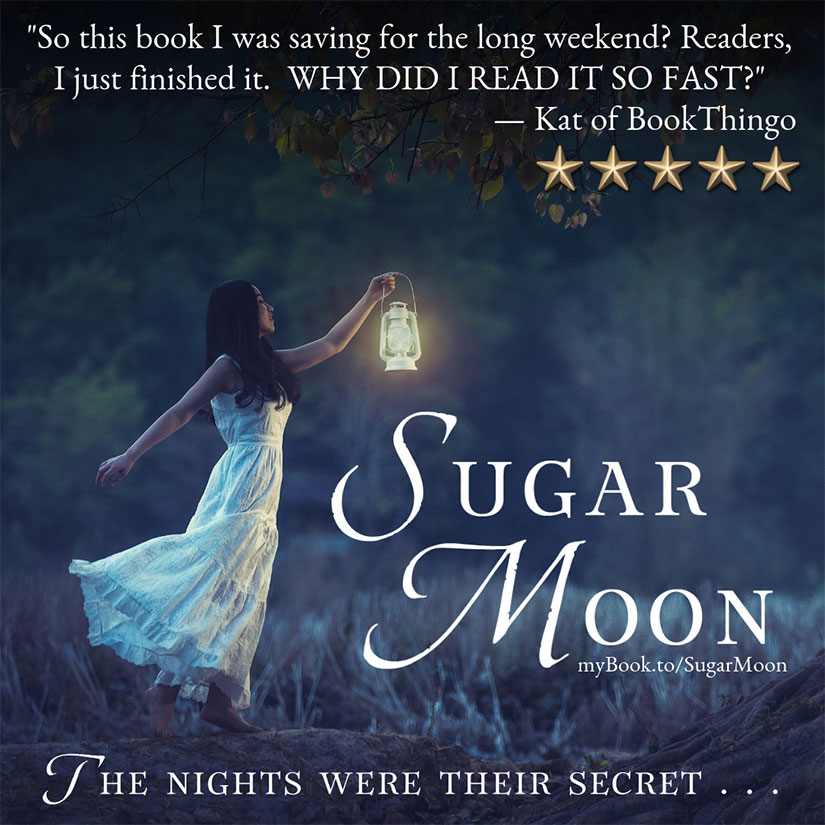

Fee was one of four authors (including another woman) of a new Philippine Education series. The First Year Book had lessons about Ramon and Adela, not Jack and Jill. They learned about carabao, not cows. Stories included the American flag, but it was small and in black-and-white, not a full-page color spread. The women went to market for fish and mangoes, and they wore traditional Filipiniana clothing. In other words, the book had a chance of making sense to the children who read it. In Sugar Moon, this textbook reboot will be put in the hands of a Filipino heroine, Allegra.

I used parts of Fee’s memoir, A Woman’s Impressions of the Philippines, for help in creating my character Georgina Potter in Under the Sugar Sun. I exercised artistic license, of course: Fee’s faithful description of the Christmas Eve pageant, for example, was turned into a courtship opportunity for my hero, Javier Altarejos.

In comparison to my careful researching of Mary Fee, I just stumbled upon Annabelle Kent’s raucous description of arriving in Manila by ship. While everyone else had horrible seasickness, Kent thought the bumpy ride a blast. The ship bucked like a bronco, and she reveled in it. As I read more, though, I found Kent’s explanation for her sturdy sea-legs: she was deaf, presumably with a damaged vestibular system. She traveled the globe by herself without an ASL interpreter, and that took guts. It seemed to have started on a type of dare. Kent wrote:

A deaf young lady made the remark to me once that it was a waste of time and money for a deaf person to go to Europe, as she could get so little benefit from the trip. I told her that as long as one could see there was a great deal one could absorb and enjoy.

I knew right then that Annabelle Kent would be my model for my aspiring journalist, Della Berget, in Hotel Oriente. At a time when American senators were making up stories rather than seeing for themselves, Kent was jumping a steamer to circle the globe and visit schools for the deaf in China and Japan. The book is one of the most joyful travel memoirs I have read.

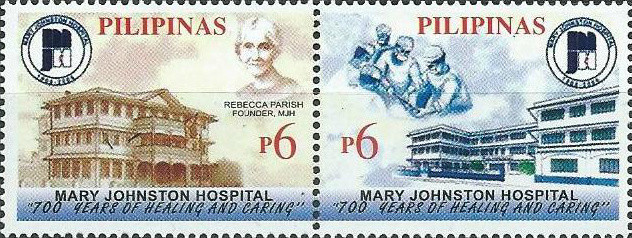

My final Gibson girl, Rebecca Parrish, was used to being a trendsetter. She was a doctor at a time when medicine was a possible career choice for a woman, but not a common one. One of her first skeptical patients in the Philippines asked, “Can a woman know enough to be a doctor?” Parrish had to prove herself a million times, by her own account, but she did.

Parrish built a 55-bed hospital in Tondo, the Mary Johnston Hospital, that operated on the principle that no one could be turned away. The hospital began its working life fighting a cholera epidemic but transitioned into a maternity clinic with a milk feeding station. Today, it is a teaching hospital specializing in internal medicine, obstetrics, gynecology, and pediatrics. Parrish also opened a training institute for nurses. If this doctor seems like a busy woman, you are correct. She wrote: “Hundreds of days—thousands of days, I worked twenty hours of the twenty-four among the sick, doing all that was in my power to do my part, and hoping the best that could be had for all.” I get tired just thinking about it.

Along with Parrish’s memoir, I have read the biographies and autobiographies of Dr. Susan Anderson, Dr. Bertha Van Hoosen, Dr. Rosalie Slaughter Morton, and Dr. Maude Abbott to put together a picture of my next heroine, Dr. Elizabeth “Liddy” Shepherd—along with a dash of artistic license, of course. (For example, I excised eugenics right out of the record, even though it was a widespread “fashion” in medicine at the time. No, thank you!)

Maybe these Gibson girls—Mary Fee, Annabelle Kent, and Rebecca Parrish—did not go “wild” in the cheap, titillating kind of way, but by contemporary standards they were as brave as Indiana Jones. My trip to Manila will be tame by comparison, but I will try to honor the memory of those who came before me…and pick the in-flight movie they would want me to see.

Featured image is “Girls Will Be Girls” by Charles Dana Gibson, found at Blog of an Art Admirer.