What is the chief end of man?—to get rich. In what way?—dishonestly if we can; honestly if we must. Who is God, the one only and true? Money is God. God and Greenbacks and Stock—father, son, and the ghost of same—three persons in one; these are the true and only God, mighty and supreme…

—Mark Twain, in “The Revised Catechism,” printed in the New York Tribune on September 27, 1871

Twain didn’t hold back, especially not when criticizing society’s ills. In fact, he is the one who coined the term the “Gilded Age” to describe a time of conspicuous consumption, wealth disparity, and pervasive corruption. Sound familiar? In fact, esteemed economists (here and here) claim that we are smack dab in the middle of a new Gilded Age: the era of the one-percenters.

The robber barons of Twain’s time were innovators, though, not fund managers. They were builders, not firm-breakers. Not to say they were moral or just men—they were definitely not—but they were self-made men who harnessed the raw power of the industrial age. Carnegie casted the steel, Rockefeller drilled the oil, and Vanderbilt laid the railroad track. Though not of noble birth—far from it—they were still the new kings, and they lived like them.

I recently traveled to Newport, Rhode Island, where the Gilded Age rich of New York spent hundreds of millions of today’s dollars building “cottages” that they lived in for only 8-12 weeks in the summer. Let me say that again: the equivalent of $30-200 million on a house used two months out of the year!

These days, the houses of Newport’s Cliff Walk and Bellevue Avenue are open to the public. Crowds mill through The Breakers, but I actually prefer The Elms, which was built by coal tycoon Edward Julius Berwind. It seems more livable—or just more endearingly excessive.

These days, the houses of Newport’s Cliff Walk and Bellevue Avenue are open to the public. Crowds mill through The Breakers, but I actually prefer The Elms, which was built by coal tycoon Edward Julius Berwind. It seems more livable—or just more endearingly excessive.

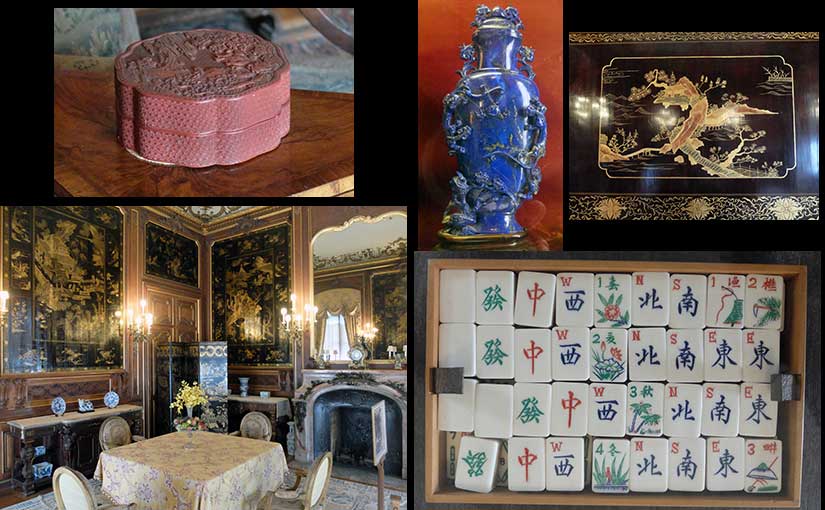

While the Vanderbilts built Italian palazzos and French châteaux, the Berwinds added mahjong and black lacquer wall panels to the mix.

An Asian touch was fitting since the Americans were not the only ones who lived large at the turn of the twentieth century. Prominent Filipino ilustrados had risen to the top by virtue of their education, their enterprise, and their mestizo connections, and they had their own gilded treasures, as the León Gallery’s recent exhibition in Manila shows.

The gallery was able to repatriate previously unknown artwork produced by Filipinos, often for European patrons, including pieces produced by Juan Luna and Felix Resurreccion Hidalgo for the General Exposition of the Philippines Islands, Madrid, 1887. The gallery owners wanted to show us that the Philippine Gilded Age was just as progressive and cosmopolitan as that of their arriving American conquerors. Javier Altarejos would agree.

Since I am stuck in New England, I had to send my always-curious friend Suzette de Borja to investigate. (Thank you, Suzette!) The furniture was beautiful. Suzette’s daughter especially loved the Manila aparador made from kamagong wood (above left), with a price tag of only P25 million, or about US$500,000.

Suzette and I have more modest tastes. I liked the bahay kubo painted on a local oyster shell, and she liked the drawing of the man with his fighting cock because it reminded her of this line of Under the Sugar Sun: “A local wag once said that in case of fire a Filipino would rescue his rooster before his wife and children—and hadn’t Georgie witnessed that with her own eyes in Manila?” You can also see a casco in the background, which is the type of boat that Della Berget comes ashore in at the beginning of Hotel Oriente. Though Filipino artists wanted to immortalize these average scenes of local life, they did so on items sold only to the very rich.

But I know what you’re saying: weren’t these robber barons or hacenderos bad people? Why are we so fascinated with them?

Well, this is romance, so we romanticize them, of course. I romanticized Hacienda Altarejos, and I knew it while I was doing it. The true history of sugar in the Philippines is a story of great injustice. If you did not know that, there is a new documentary out there to guide you through that reality called Pureza: The Story of Negros Sugar. The Gilded Age was fraught with labor disputes on the other side of the Pacific, as well: the Pullman Strike, the Haymarket Riots, the Coal Strike of 1902, just to name a few. This was the other reason Twain used the term Gilded Age, because all that glitters is not gold.

But historical romance is fascinated with the obscenely rich, and the more chaotic our current lives the more we seek a lifestyle of security. Many of us were raised on fairy tales of prince charmings of one sort or another—and we hardly spared a thought about the peasants of the kingdom. I teach my students about the horrible injustices of the early industrial age, but you better believe that John Thornton of Elizabeth Gaskell’s North and South gets my engine going! (And, yes, it helps that he is played by Richard Armitage in the BBC version on Netflix.) Gaskell wrote her novel in 1855—smack dab in the worst excesses of this period—and she still made a factory owner swoon-worthy.

What about our Regency bookshelf? We don’t ask where Fitzwilliam Darcy got his ten thousand (pounds) a year—which, in present value, could be close to $6 million, or, in prestige value, maybe as much as $18 million. Yes, he earned interest on government bonds, but where did he get his principal wealth? From the sweat on the brows of farmers on “his” estate, of course. And, according to Joanna Trollope, Pemberly was built on the proceeds of coal mines. As a granddaughter of a coal miner, I can tell you that line of work not only sucks but will also kill you.

And it gets worse: men like Darcy were probably invested in another lucrative crop, one grown across the Atlantic in the West Indies. You guessed it. Sugar again! This was the “dark underbelly” of the British peerage, according to Trollope. And the sugar industry in the Caribbean and South America was the worst in the world: the average life of a slave there was five years. Hacienda Altarejos is practically a hippie commune, in comparison.

So, if we squint hard, we don’t see the nasty side of our historical romances, leaving only the great parties, the family sagas, and the romantic intrigue. (See an expanded discussion of the fabricated chronotopes of historical romance from a paper I presented at IASPR in Sydney in June 2018.)

The thing about Gilded Age tycoons—whether American or Filipino—in comparison to our Regency heroes is that at least they had to do something to earn their money. This was the era of (at times toxic) manliness. You were supposed to roll up your shirtsleeves and get your hands dirty:

Javier placed the shovel in line with the stones, put his foot on the top of the blade, and pushed it deep. It slid into the soil. Georgie watched Javier reach down and grip the handle low, a position that gave him more control. He lifted the earth and placed it carefully to the side. When he raised his foot again to the top of the blade, the tight line of his trousers revealed a strong thigh and backside. Color rose to her cheeks. She felt a whole different kind of dirty watching him.

If you want more Gilded Age romance, Joanna Shupe’s Knickerbocker Club series has a very delicious hero, Emmett Cavanaugh, whose rags-to-riches story was the embodiment of everyone’s hopes and dreams in the period.

Emmett is rough, yet gentle. Arrogant, but thoughtful. He’s that classic Type A hero we love so much, but instead of spending his excess energy whoring or hunting as a peer would do, he’s actually got shit to do. (He does box, though.)

Another Gilded Age merchant-on-the-rise can be found in Marrying Winterborne by Lisa Kleypas. Rhys Winterborne is a Welsh department store owner, a terrific choice of occupation since these diverse enterprises, selling all types of ready-made goods to the blossoming middle class, were an industrial age phenomenon—a true “retail revolution.”

Do not forget that all of these men would have been snubbed by the vaunted ton of London. John Thornton, Emmett Cavanaugh, Rhys Winterborne, and Javier Altarejos—none would have received an invitation to Almack’s. But, as Kleypas herself said: “There’s something invigorating about a hero who has created his own success.”

If you want Gilded Age romance that transcends the chronotope, check out Piper Huguley’s Migrations of the Heart series that “follows the loves and lives of African American sisters during America’s greatest internal migration in the first part of the twentieth century.”

Enjoy your self-made Prince Charming!