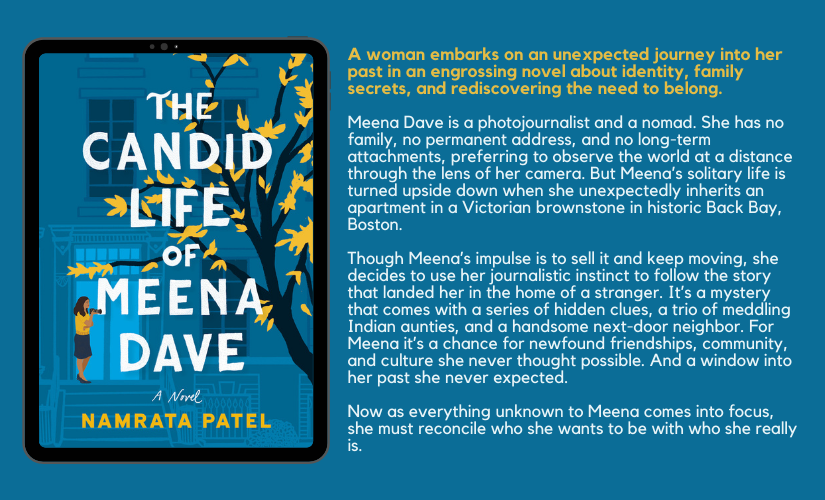

The Book

Namrata Patel’s writing “recipe” blends complex heroines, Gujarati food, and global families—a meal in three delicious courses. I have sampled several of Nam’s unpublished manuscripts, as well as her home cooking, and they have all been delicious—but it is her published debut, The Candid Life of Meena Dave, that is the book feast you have been waiting for.

The Candid Life of Meena Dave is available for pre-order now on Amazon, Audible, and elsewhere. It will be released on June 1, 2022, by Lake Union Publishing. It is marketed as women’s and Asian American fiction, not romance, but there is an achingly perfect love interest. (And I think you’ll love Sam as much as I do!)

The Interview

Thank you, Nam, for coming here to the History Ever After blog. I am going to be geeking out on history with my questions, but that won’t surprise you or anyone else.

1. What inspired you to write Meena’s story?

It was the early days of the pandemic, and we were all trying to navigate this unknown event in our lives. For many of us, we were doing it alone. Overnight, our world shrunk to what was within the four walls. And we were all experiencing some of the same in terms of living inside versus out. For me, I wanted to write about things that I couldn’t quite resolve. This story came from that, especially around what does “community” mean? I used to define that word very broadly in terms of cultural identity, ethnicity, professional networks, family, friends—a catch-all for the people in my life. During the early days of isolation, the scope of that definition changed, narrowed. Through that, this story was born. What if a person felt alone in the world because they define community in a very narrow and perhaps literal sense (e.g. family)? What would it take for them to notice that you can build one, be invited, and find a sense of belonging? Usually what helps inspire a story is something that I’m trying to work through myself.

2. Can you tell us a little of the history that inspired the Engineer’s House?

Oh my gosh, yes! I’ve always been fascinated by my Gujarati American identity and history. Growing up, I was only exposed to it by my parents who told stories about their lives—my father was born right before the Partition, so he’d lived under British rule of India for a bit. I didn’t get much of that in history classes, which are usually taught through an American and/or western lens, even world history.

In college and later grad school, I leaned into diaspora, dual-cultural identity creation, and anything that helped me understand my place in this country. Most of what I’d learned was generalized desi American experiences. Post grad school, I continued to stay current through non-fiction books and academic papers.

A few years ago, I learned about Ross Bassett, a history professor who cataloged every Indian graduate of MIT from the beginning to 2000. He published a paper MIT-Trained Swadeshis: MIT and Indian Nationalism, 1880–1947. When I read through it, a short paper by academic standards, I was floored. It was a part of my history that I never knew. Over a 100 Gujrati Indians came to MIT and studied here before the Partition in order to go back to India and rebuild its infrastructure. I tried to learn as much about them as possible, but there wasn’t a lot. Most of my hyphenated history is around the major immigration of Indians and other desis in the eighties and nineties. This was well before that.

I kept thinking of what it must have been like for them, to be brown, to not have access to their familiar culture like food, language, ability to worship, and all that gives us a sense of community.

That’s when the premises of the Engineer’s House emerged for me. What if there were (fictional, of course), a few who were the constants? What if two or three desi men—they were all men by the way—stayed to welcome each new class and wave off those who graduated? Then they built families here, stayed on, and assimilated to America. Each subsequent generation that followed had more of a connection and a sense of place to this country than India.

So I created the Engineer’s House as a place where they would have lived, became hyphenated, and lived communally. One reason, of several, I chose to set the house in the Back Bay area of Boston is because this is still a very white space historically, and I wanted to put a brown community within it because these aunties had come from wealth in India and continued to live as such by building their own status and wealth here.

I’ll stop here—but as you can imagine, I can talk about this for pages!

3. I know from personal experience that you are a talented Gujarati cook. Can you tell us a little bit about your favorite dishes in the book?

I had fun thinking about food in this novel. One thing that happens to food when immigrants move to a new place is fusion—it’s not just for chefs. Women (mainly) create with what’s available, and the original traditional diet/cuisine evolves as part of assimilation.

My mom does this. I grew up eating desi lasagna which has cumin, coriander, and other traditional spices. Tomato soup came out of a can, but then was mixed with veggies and spices to change the flavor.

So I kept thinking, how and what would the aunties have learned—especially from parents and grandparents who brought spices over in suitcases because Patel Brothers wasn’t a thing yet? That’s where tandoori turkey and fish curry came from. Gujaratis are agrarian and vegetarian, but in the States, we’ve assimilated. I mean I love a good steak once in a while! So the aunties doctored up Thanksgiving and made it their own.

I will say the scene with the sabudana kichdi is my favorite because that is a traditional dish that has stayed the same for generations. As with a lot of desi cuisine, each family makes it their own, and this is my mother’s recipe. However, NYT Cooking offered up one a few years ago, which comes close. I wanted to make sure the book conveyed what changed and what was kept, culturally, via food.

4. Is your second book a part of this same world? Have we met any of the characters yet?

No. The second book is a stand-alone about a perfumer who loses her sense of smell and actively tries to get it back. In the process, she learns how to adapt and discovers that you can have more than one passion. It’s set in northern California and also examines the history of Indian hotel owners in the US.

A big thank you to Namrata Patel for answering my pesky questions. And grab your copy of The Candid Life of Meena Dave today.