It’s game time! Now that American football season is over, I need a new hobby. I love old school games, and you cannot get more old school than these two.

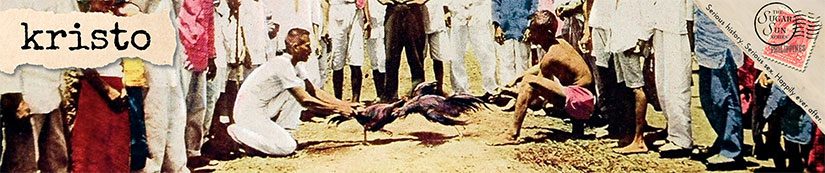

According to a fantastic site (linked below), one of the first Jesuit priests to arrive in the Visayan islands, Father José Sanchez, wrote in 1692 about sungka, called kunggit in parts of Panay. Sungka is a form of mancala, the “sowing” or “count and capture” games known across Asia. However, it is distinctive enough in its play that it has become a cultural touchstone for Filipino migrants and overseas contract workers.

Sungka is played on a carved wooden board with seven small “houses” (bahay) and one head (ulo) at either end. Small stones or cowrie shells are placed in the houses and then redistributed in gameplay. The Filipino version has two especially cool rules if you’re a mancala enthusiast. For example, the first move is played by both players simultaneously, and the player who runs out of stones first gets the next turn. Second, you can capture your opponent’s pieces across from you when you land in an empty house on your side. These changes make the game both more fair and more fun.

Beyond mere entertainment, sungka has been used to teach advanced mathematical concepts and to divine one’s marriage prospects—so everything important in life. “The feminist poet and communication scientist Alison M. De La Cruz wrote in 1999 a one-woman performance called Sungka, which analyses the societal and family-related expectations in regard to gender-specific behavior and sexuality, race, and ethnic affiliation, by comparing it to a game of sungka.” That sounds interesting, eh?

Panguingue is a 19th-century rummy card game that uses eight traditional Spanish decks. You can make your modern deck a pseudo-Spanish one by removing the 8s, 9s, and 10s, and some folks also remove a set of spades to make 310 cards total. With these cards removed, the jack follows the 7 card. This game is similar to the in-hand rummy you might already know, but one interesting distinction is the fact that you can fold your entire hand in the first move before you bet. After that, you’re in it until someone wins it. Wait a second, you say. Betting? Oh, did I not mention there can be lots of gambling involved? That’s the exciting bit.

A great site on sungka: http://mancala.wikia.com/wiki/Sungka

A ongoing blog on panguingue: http://panguingue.blogspot.com/