As Fernando Zialcita and Martin Tinio Jr. wrote in their beautiful book, Philippine Ancestral Houses: “Southeast Asians share many things in common: patis [fish sauce], bagoong [fermented fish paste], certain linguistic patterns, and a high regard for women’s rights. But the most visible symbol is surely the ubiquitous house on stilts.”

In the Philippines, if you are looking for traditional architecture untouched by Spanish and American influences, look no further than the bahay kubo, or “cube house.” And though there are many regional variations, in the lowland areas a cube is a perfect description:

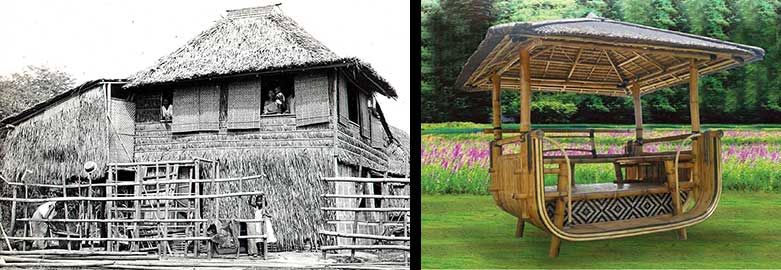

These houses are usually about fifteen feet square, with one large room, and are raised about six feet from the ground. Under the house is kept the live stock. When the family has a horse or cow or carabao the house is ten feet from the ground, and these animals are stabled underneath. In nearly every house or yard may be found a game cock tied by the leg to prevent him from roaming and fighting.

Americans often called these residences nipa huts, even though not all have roofs of thatched nipa palm. Anahaw palm leaves or cogon grass are similarly popular.

The frames are made of coco lumber, hardwood (if you were rich), and split bamboo. Again, here is Zialcita and Tinio:

A unique feature of the bahay kubo is that its floor is, by turns, a horizontal window, a permanent bed or a basket, for it is made of thin bamboo slats, each around two and a half centimeters wide and spaced from each other at regular intervals. Even when the wall windows are closed, light and air pass through the floor to ripen piles of vegetables or to soothe anybody sleeping on the well-polished slats. At the same time, waste matter can be thrown out through the gaps….For bodily needs, there are always the bushes; at night, however, especially when it is storming, the slatted floor becomes a convenient enough substitute.

Call me spoiled, but when my husband had our own bahay kubo built on our farm, I had him install a toilet. It was still bucket flush, but you’ve got to admit it was nice. His own choice of improvement was a wind turbine to power our computers, stereo and speakers, and wifi access. It was definitely a twenty-first century kubo.

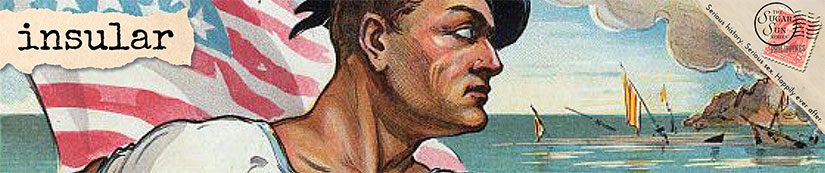

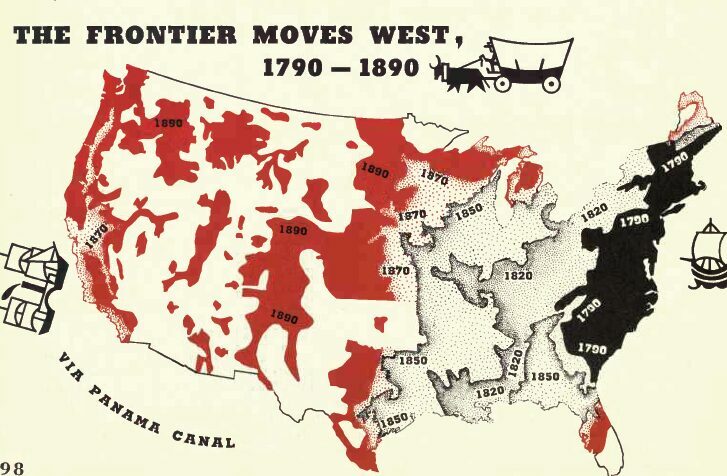

Early American writers were fascinated with the one-room living accommodations of most Filipino families—how quickly they had forgotten that working-class houses in the United States and Europe were frequently one room per floor, and American frontier homes were single rooms, as well. In these northern hemisphere cases, the choice was essential because it was the easiest way to heat a home around a single stove. Where I live in New England, every town has proudly preserved its original one-room schoolhouse. But this is not all past glory. The single-room style has come back to modern architecture, just with a new name: open plan.

Of course, the bahay kubo does take open plan a step further than we would like—a step right into the bedroom. As Zialcita and Tinio wrote: “Nor does each member insist on a well-demarcated sleeping territory, a mat unto himself. Children sleep with their parents and grandparents on the same mat till they are ready to marry.” Again, though, this was the norm in American households through the early twentieth century. Either that, or you let the children sleep in the attic, which is exactly what Louisa May Alcott did at her house in Harvard, Massachusetts, at the Fruitlands Museum. I’ve seen her bunk, and I think I’d prefer a mat in the open-plan kubo.

The bahay kubo was actually ahead of its time in many ways. It was not only well suited to its environment, but friendly to the environment, as well. Architect Angelo Mañosa has said:

In its form, it already embodies all the design principles we think of as ‘green.’ It is made of low-cost, readily available indigenous materials and it is designed for our tropical climate: the tall, steeply-pitched roof sheds monsoon rain while creating ample overhead space for dissipating heat, the long eave lines provide shade. The silong underneath the house creates a simple, utilitarian space while allowing ventilation from below through the bamboo slat floors. The large awning windows, held open by a simple tukod (sturdy rod), provide cross ventilation and natural light. All of the materials used in it are organic, renewable, and readily available at little cost. And yet it is strong enough to withstand typhoons. The bahay kubo even survived the ash fall from Mt. Pinatubo, when more ’modern’ houses collapsed.

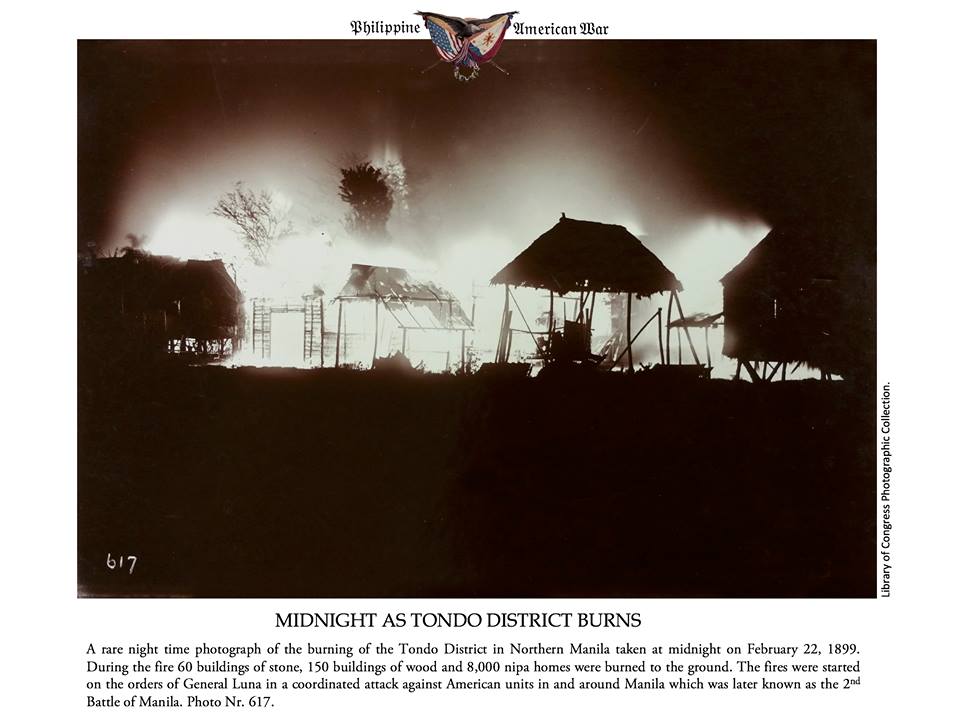

This is all true. However, Zialcita and Tinio are a little more ambivalent about the kubo’s resistance to the elements. As they point out, it does sway with the shock of an earthquake. “Indeed, even without earthquakes, the bahay kubo sways to and fro when someone within runs or moves about brusquely. Repeated shocks, however, can collapse the bahay kubo.” Moreover, it is no match for a strong typhoon. And then there’s fire.

While the above Tondo fire was believed to be set by insurgents, the Americans torched their fair share of homes. In fact, it was sometimes policy:

A piece of fiery thatch floated through the air near [Georgie’s] head. A fresh gust of wind blew it up and over the street toward a cluster of neighboring homes whose occupants were still in the process of pulling out their belongings. The fireball rose and fell, dancing through the dark sky in slow motion, until it landed on the grass roof of one of the huts, igniting in seconds.

Everyone, including the firemen, rushed to warn those inside, but somehow Georgie got there first. She climbed the ladder into the hut and found a small boy holding a baby. He looked at Georgie with wide eyes as if she, not the fire, was the monster devouring his home.

—Under the Sugar Sun

In the opening scene of my novel, the cholera police have set fire to a whole neighborhood to rid the area of disease—which, in fact, was one of the methods that American officials used in the terrible epidemic of 1902. (They believed they were being scientific, but they probably scattered the carriers of the disease farther than the old Spanish system of in-home quarantine.) I think that part of the American willingness to torch the homes was a suspicion of the kubo, which wore off on the locals, too.

It is true that kubos are not that durable. According to Zialcita and Tinio again, the bamboo rafters only last through about five rainy seasons, the rest of the bamboo becomes brittle in a decade, and (from my own experience) cogon roofs need to be patched and replaced far more often than corrugated iron. Some provinces like Surigao Del Norte still brag that over 50% of their houses’ roofs are made from natural materials, but city residences have embraced utilitarian concrete (and air conditioning). (Stone was a choice of the Spanish and mestizo elite, but most of the non-volcanic kind had to be imported, so it was not an option for most.)

You cannot blame people for choosing the most long-lasting and comfortable option available to them individually, but at what social cost? How much material culture has been lost? In 2014 a town in Pangasinan revived its bahay kubo heritage with a fiesta display on the town square. Each of 21 barangays competed to build the best kubo to showcase its construction skills and to promote the local bamboo industry. But how long before a village cannot find someone to build a real, quality kubo—not just one of the roadside-style gazebos? Of course, this is an easy question for an academic like me to ask, but I did not live in my own kubo full time. Fortunately, Angelo Mañosa has come up with 18 ways to use the design elements of a bahay kubo as a template for a green modern house, a fitting way to preserve history and embrace the future at the same time.