[This is part 2 of a series on the Spanish-American War. Read Part I here.]

Cuba: a country so pretty, so well located, and so full of profitable sugar plantations—some owned by Americans—that a group of U.S. ambassadors in Europe considered offering Spain $120 million for it in 1854. Yes, these ambassadors did meet at the request of the American secretary of state, but keep in mind that diplomatic posts back then were given to adventurers not known for their actual diplomacy. The plan leaked, and the northern states grew alarmed that this might be a back-door plot to expand slavery. The whole thing was quickly scuttled. When the Civil War broke out, people forgot Cuba for a while.

The Cubans had not wanted the Americans to take them over—but they didn’t want the Spanish to stay, either. They launched a revolution in 1868, seeking total independence, and they were happy enough to work with individual Americans toward that goal. The Cubans purchased an old Confederate blockade runner called the Virginius under an American frontman, and the ship began transporting guns and men to and from the island under a hastily-raised American flag. When the Virginius was captured by the angry Spanish in 1873, many of its officers were summarily executed, including several Americans and Brits. War drums began to beat. Yankees talked of action against Spain, but it was so soon after the end of the Civil War that few intended to go through with their threats. The moment passed.

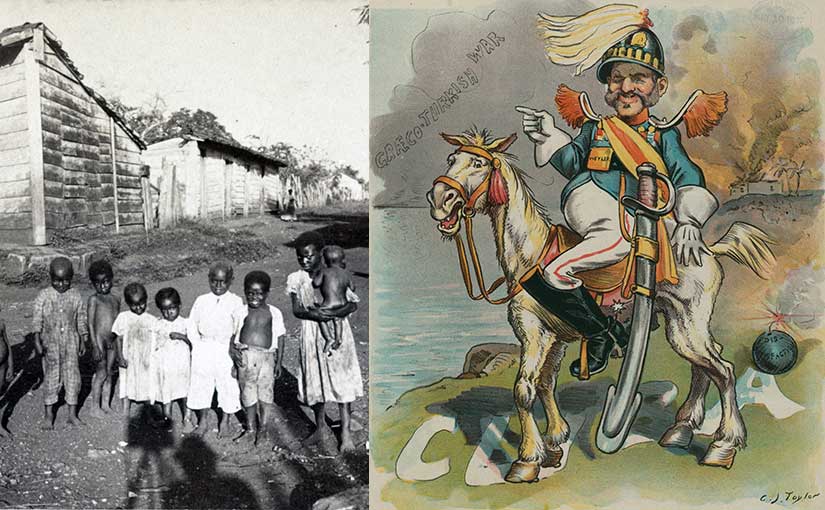

The Cuban revolution flared up again in 1895. It was an ugly war on both sides. Guerrilla war always is. The Spanish general Weyler was criticized in the American press for his reconcentrados: “protected zones” that cut civilians off from the rebels they supported. Conditions in these concentration-camp towns were abysmal, and anyone outside of one could be shot on sight. (American outrage over the reconcentrados would have been more laudatory if the US had not repeated the tactic in the Philippines in 1901—a truth that would be acknowledged in the contemporary press.)

Sensationalist newspapermen roused the American public into a frenzy, and the Spanish inadvertently helped them. For example, a letter by the Spanish ambassador Enrique Dupuy de Lôme was intercepted and published by William Randolph Heart in his New York Journal. In the letter, de Lôme said:

[US President William] McKinley is weak and a bidder for the admiration of the crowd besides being a would-be politician who tries to leave a door open behind himself while keeping on good terms with the jingoes [extreme patriots who advocate an aggressive foreign policy] of his party.

De Lôme was not wrong, but it still got him recalled to Madrid because Spain was desperately trying to avoid war with the US. In fact, in an attempt to pacify the revolutionaries, Spain offered Cuba and Puerto Rico enhanced local autonomy—an offer that the Puerto Ricans took up. San Juan received its own constitution, a bicameral legislature on the island, and continued representation in the Spanish legislature. Puerto Rico was in the process of putting together its new government when US gunships arrived. An often overlooked aspect of the Spanish-American War is the fact that in the name of democracy, the United States extinguished democracy. Americans “saved” Puerto Rico from the Spanish, yet the Spanish were actually giving that island MORE representation in 1898 than the United States Congress gives it NOW. Think on that a minute.

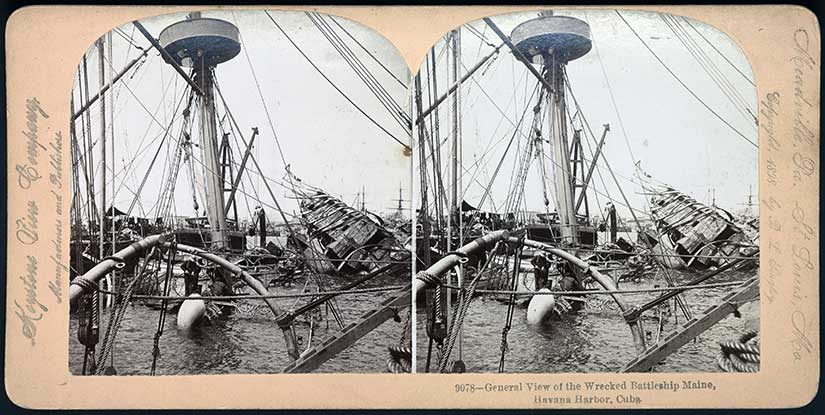

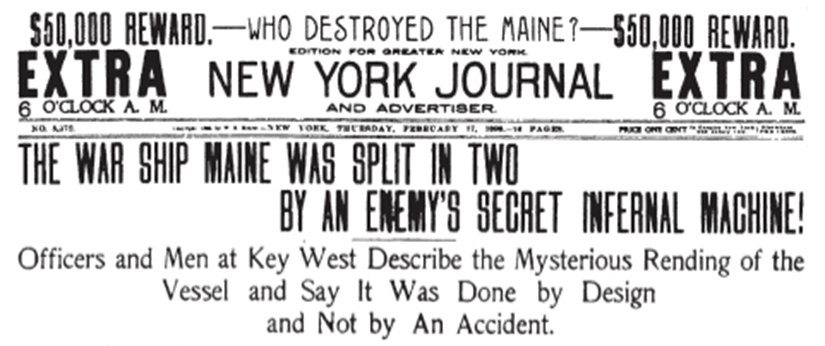

If the Spanish were trying to avoid war, then why did it still break out? Of course, you know: “Remember the Maine!” That is probably the one thing the average American history student does remember about the war. The explosion of the USS Maine in Havana was almost certainly due to a coal fire igniting a reserve magazine of six tons of gunpowder, much of which was already degrading due to the humid climate. The navy’s leading weapons expert, Philip Alger, actually said this at the time—and got called a traitor by Theodore Roosevelt. Yet, what Americans knew came from their papers, and the papers said:

“A secret infernal machine! Oh no! Let’s get those jerks!” went America. To make a long story short, Congress added $50 million to America’s defense budget and—to satisfy the non-imperialists—passed an Amendment that the US would not colonize Cuba. (Nothing was said about Puerto Rico, the Philippines, or Guam.) President McKinley asked Congress for a declaration of war, though Spain—with few options left—did him the favor of actually declaring first. Congress followed suit the next day. American boys lined up at recruiting stations all around the country, anxious to prove their manhood.

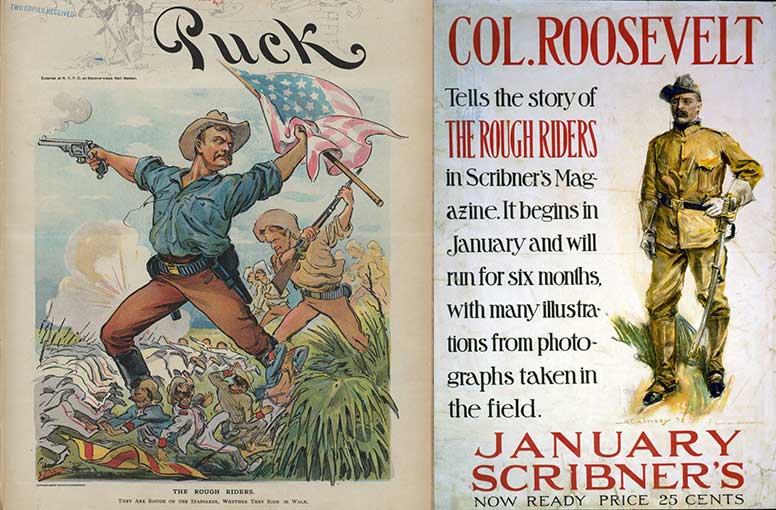

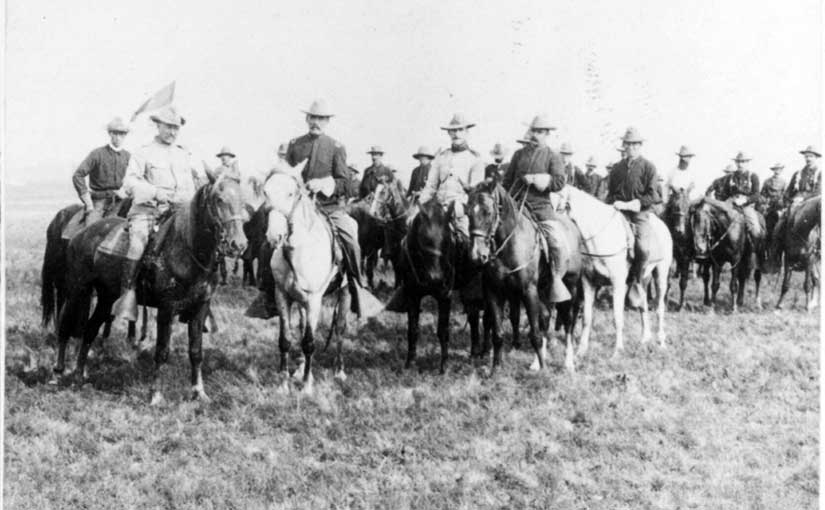

Roosevelt resigned his post as Assistant Secretary of Navy and recruited his own calvary unit, made up of (1) Ivy League boys (seasonal hunters who knew how to ride horses and fire guns); and (2) white cowboys (who could also ride horses and fire guns, maybe better than the Harvard boys, and they were so much more manly in Roosevelt’s eyes). The 1st United States Volunteer Cavalry was known as the Rough Riders. Fun fact: later on in the war, American soldiers with venereal disease in the Philippines were known as “rough riders.” How droll.

Roosevelt’s focus on male virility in what he called the “strenuous life” was something he practiced as well as preached. He had suffered from very bad asthma as a child, but he still pushed himself to become a college athlete and active rancher. Roosevelt believed that peace itself was a weakness.

I have even scanter patience with those who make a pretense of humanitarianism to hide and cover their timidity, and who cant about “liberty” and the “consent of the governed,” in order to excuse themselves for their unwillingness to play the part of men.…Their doctrines condemn your forefathers and mine for ever having settled in these United States.

To prove he was no “over-civilized” man himself, Roosevelt wanted to be in the thick of the action, and his unit fought enthusiastically in Cuba, shaming others into action with eager charges. Or so the carefully cultivated legend goes, aided by the press that Roosevelt brought with him. In fact, Mr. Charles McKinley Saltzman, a white graduate of West Point and a veteran of the Cuba campaign, praised the Ninth and Tenth Cavalries and 24th Infantry—all African American regiments—for charging San Juan Hill in support of Roosevelt. Saltzman said that these units “did much to save the Rough Riders from being cut to pieces.”

Roosevelt tried to convince the nation that the Black soldiers were only helpful because they were “dependent upon their white officers,” and that he had to force some runaways back to the front line by point of a pistol. According to the New York State Military Museum, a former Sergeant in the 10th Cavalry said that “Roosevelt actually stopped four soldiers on their way to pick up ammunition from a supply point.” If you are looking for a little schadenfreude, Roosevelt lobbied the War Department hard for the Congressional Medal of Honor for his efforts, but they did not give it to him in his lifetime. He was finally granted that honor during the last days of the Bill Clinton administration in 2001. (In contrast, five African American cavalry soldiers and one naval fireman won Medals of Honor for their part in the battle for Santiago, Cuba.)

The war that Roosevelt fought in Cuba was the one that American volunteers thought they were signing up for. Nevertheless, many boys actually found themselves somewhere entirely different: the Philippines. The bait and switch was partly Roosevelt’s doing. It was Roosevelt who told Commodore Dewey, who was in the Pacific, to steam toward Manila and lob the first cannon shot of the entire war there. Later, American troops were sent from the Philippines to China to put down the Boxer War in 1900. Maybe the term “mission creep” is familiar to you? Stay tuned for more.

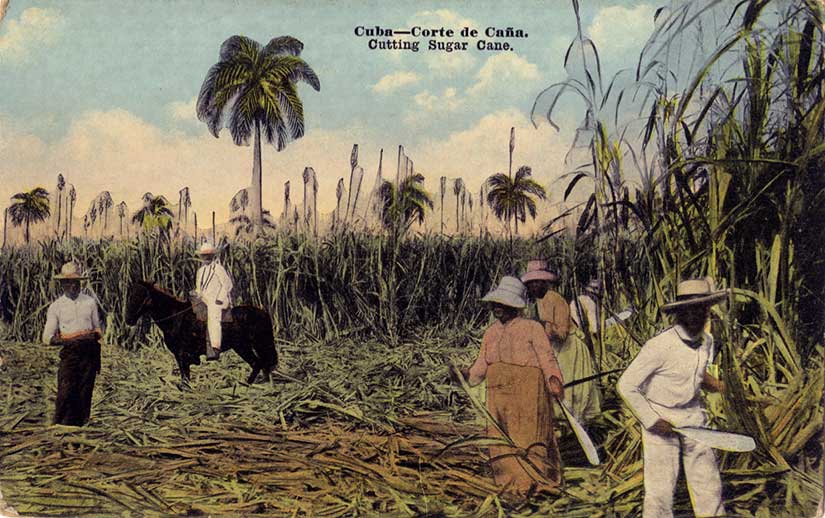

Featured image (at the top of the post) is a 1919 postcard of cutting sugar cane in Cuba.