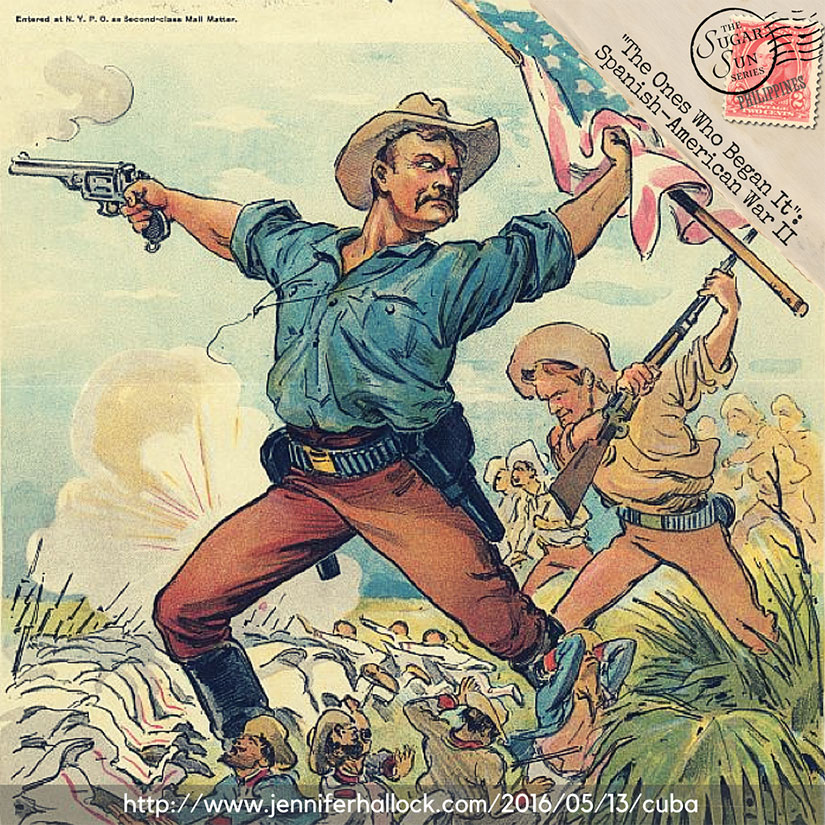

This is the story you may have heard: Theodore Roosevelt built the second half of his national political career on his reputation as a hero from the Cuban theater of the Spanish-American War. As a lieutenant colonel with the 1st US Volunteer Cavalry Regiment, also known as the “Rough Riders,” Roosevelt promoted his own efforts in the fight to liberate Santiago, Cuba. His friend, Colonel Leonard Wood, helped create the legend by reporting to the War Department, “I have the honor to recommend Lieut. Col. Theodore Roosevelt . . . for a Medal of Honor for distinguished gallantry in leading a charge on one of the entrenched hills to the east of the Spanish position in the suburbs of Santiago de Cuba, July First, 1898” (Yockelson 1998, 3).

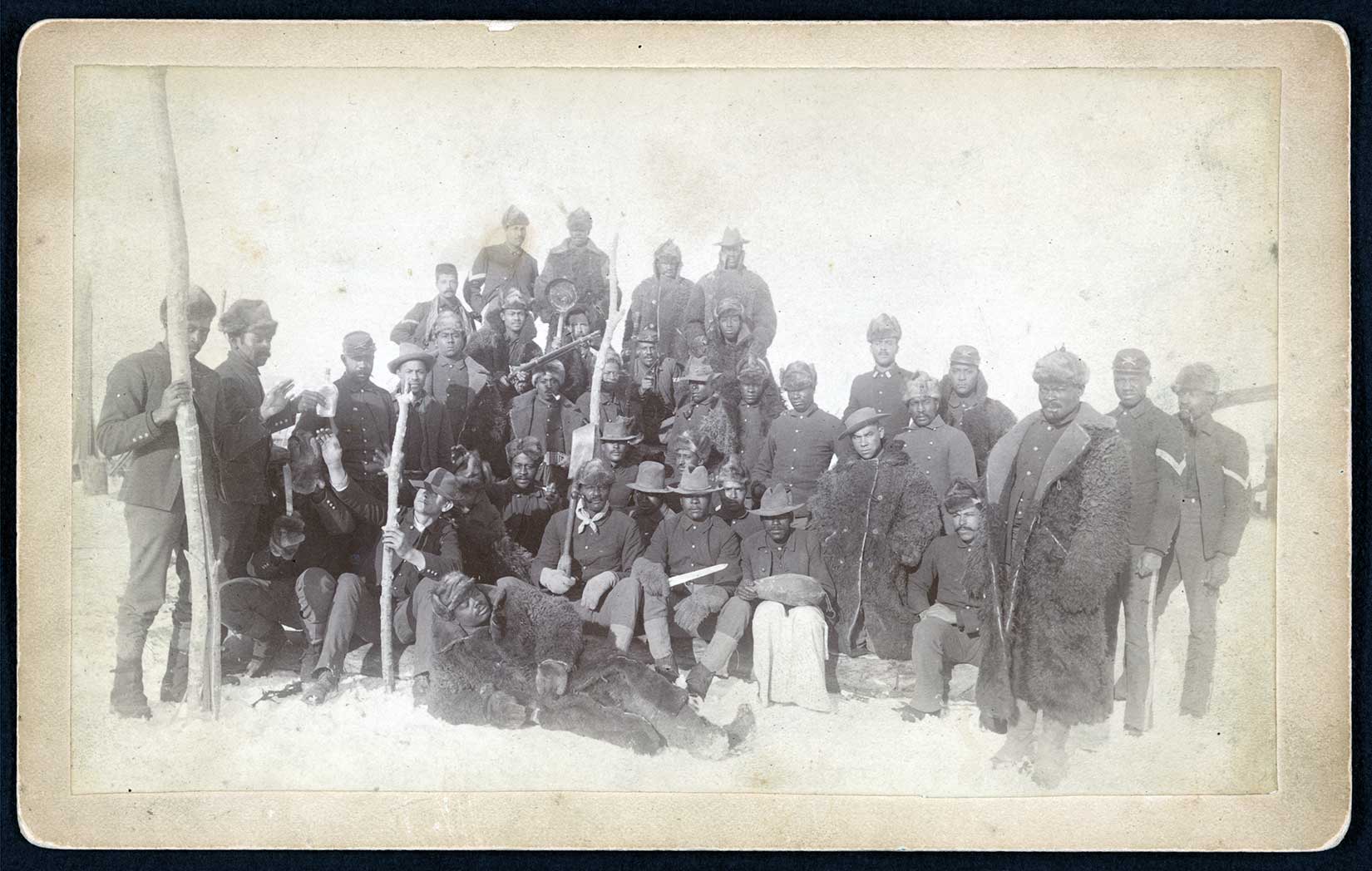

This is the part you probably don’t know: Wood was not at the battle, and those who were there would tell a different story: Roosevelt and his Rough Riders owed their victory and probably their reputations to the African American regiments who saved their hides. These were the same troops Roosevelt would later disparage and, in some cases, dishonorably discharge by executive order.

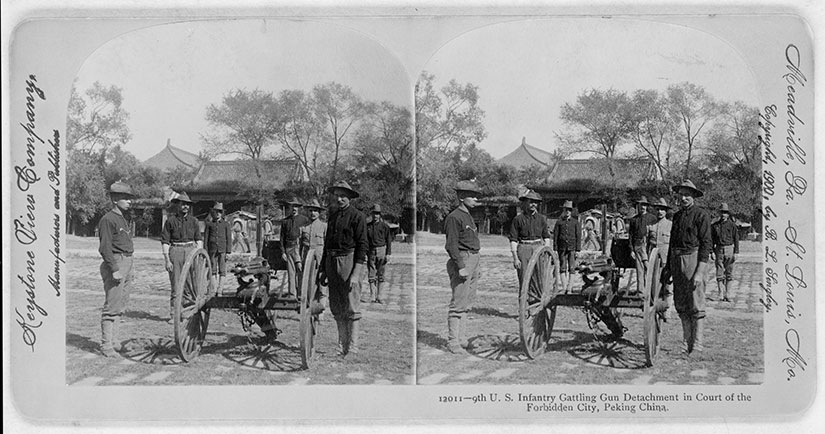

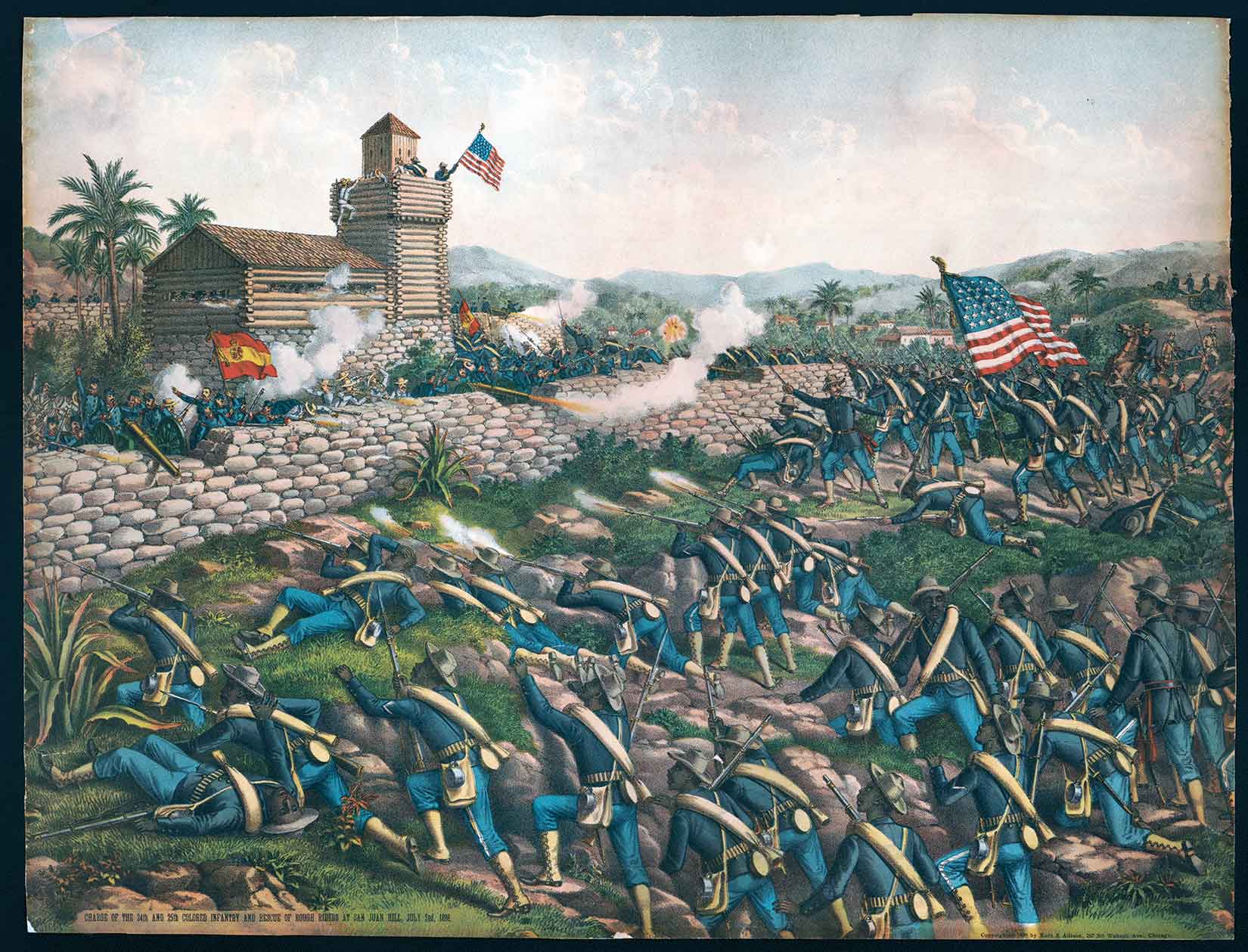

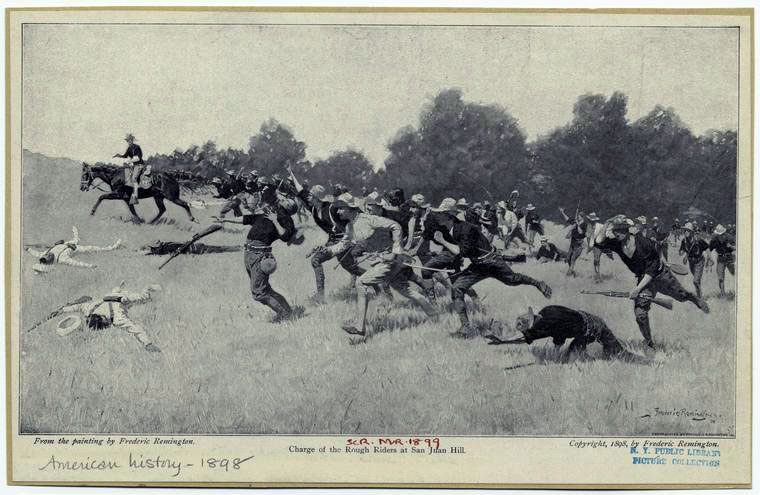

Mr. Charles McKinley Saltzman, a white graduate of West Point and a veteran of the Cuba campaign, praised the 9th and 10th Cavalries, along with the 24th Infantry, for charging San Juan Hill in the most integrated battle of the war. He said that these African American soldiers “did much to save the Rough Riders from being cut to pieces” (“Compliment to Colored Soldiers,” 1). The 24th Infantry “bore the brunt” of the fighting—and though they were specifically targeted by the Spanish, they stood their ground and performed challenging maneuvers “under the hottest fire of the day” (“Colored Troops Win Praise from the White Press,” 2).

A reporter from New York said that the 10th Cavalry advanced, “firing as they marched, their aim was splendid. Their coolness was superb and their courage aroused admiration of their comrades” (New York State Division). First Lieutenant John “Black Jack” Pershing—a hero who would fight in the Philippines and eventually become the American commander in Europe during World War I—also agreed that the 10th Cavalry saved Roosevelt’s forces. Rough Rider Frank Knox himself called the 10th Cavalry “the bravest men he had ever seen” (New York State Division). A white corporal, who would also admit to his prejudice against Black Americans in general, was quoted saying: “If it had not been for the Negro Cavalry, the Rough Riders would have been exterminated” (“Gov. Tanner’s Speech,” 4).

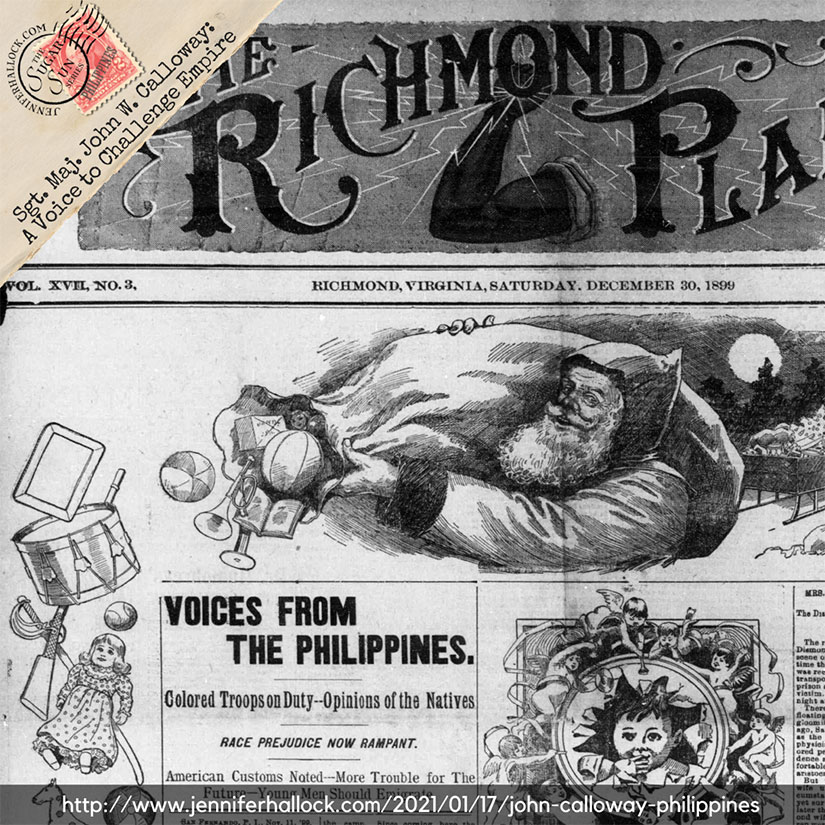

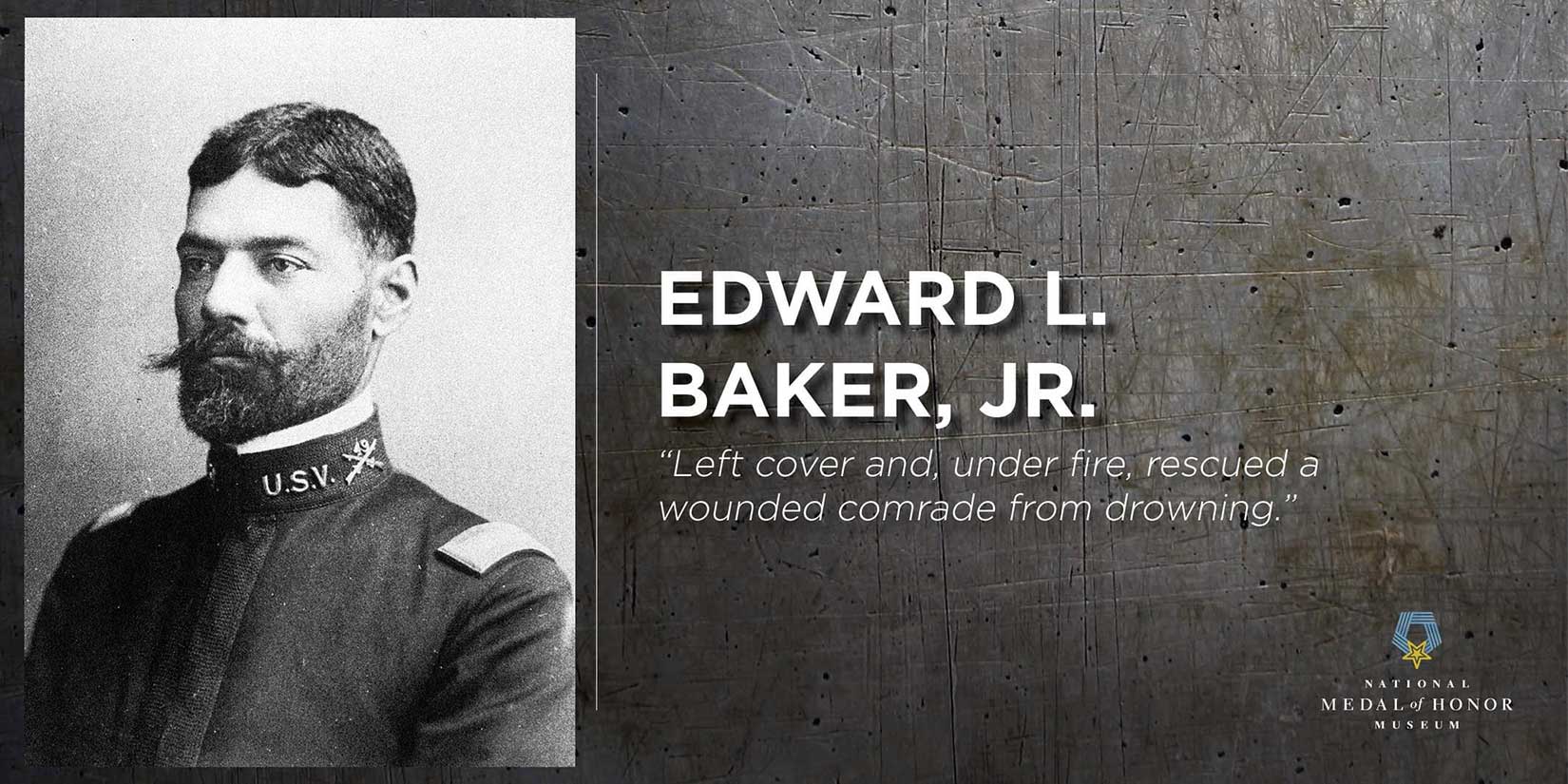

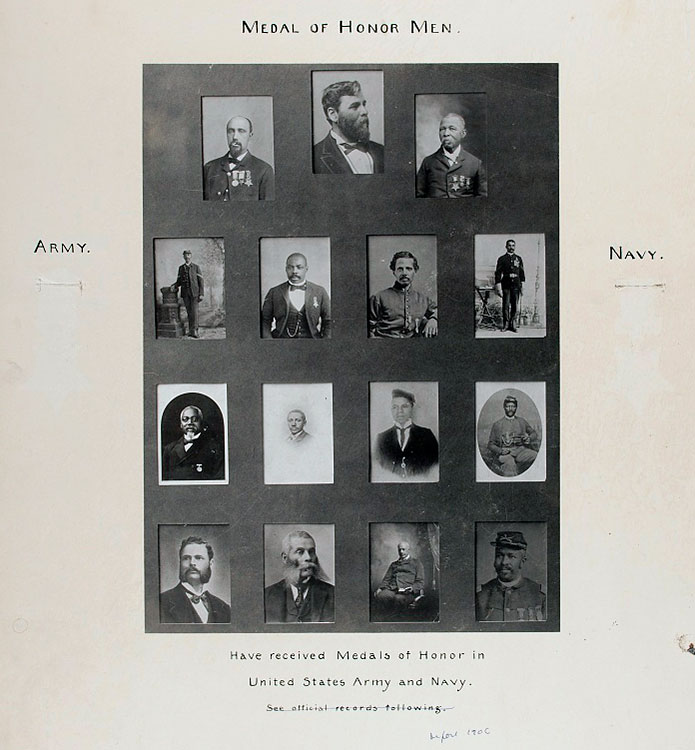

The Richmond Planet, an African American community newspaper, forecasted that though these soldiers had been “a right useful ‘article’ when white troops are in a tight place” (“Gov. Tanner’s Speech,” 4), they would not be properly recognized. That is not entirely true. A few were: five members of the 10th Cavalry received the Congressional Medal of Honor, America’s highest and most-prestigious personal military decoration, as did a Black naval fireman on the USS Iowa off the coast of Cuba.

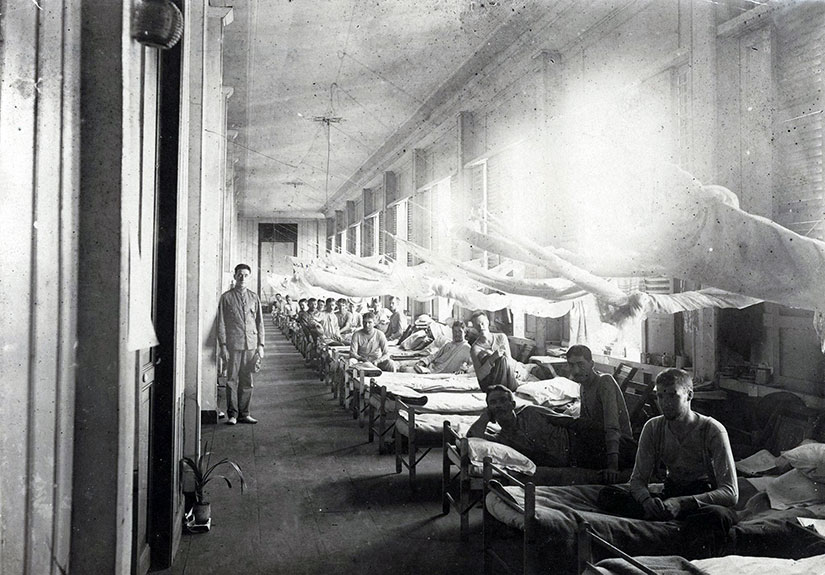

Twenty-five other soldiers from African American units were awarded the Certificate of Merit, the second highest award at the time (New York State Division). But those who did not survive Cuba did not receive their due posthumously. In fact, they were not even brought home to be buried like the fallen Rough Riders and other white officers. Instead, after suffering a 20% casualty rate (New York State Division), the African Americans killed in combat were buried in unmarked graves on the San Juan Heights near where they fell (“President McKinley and the Negro Soldiers,” 1).

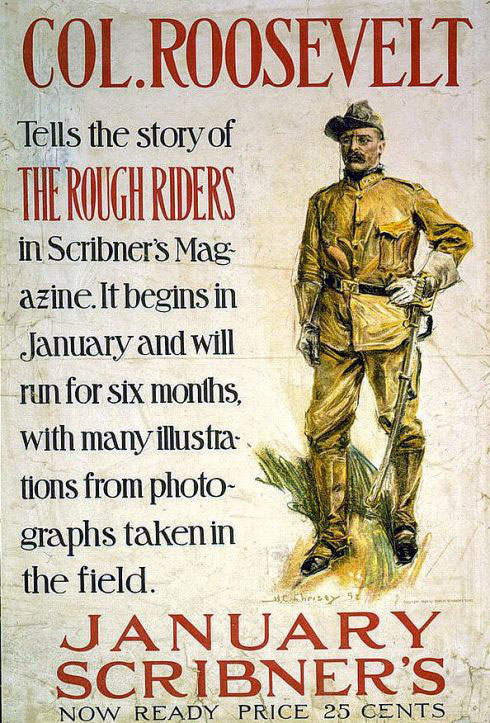

How did Roosevelt get the credit? He had “friends in the newspaper business [who] ensured that his exploits in Cuba were not overlooked by the public” (Yockelson 1998, 1). And it did make a good story: the rising star of the Republican Party had overcome debilitating asthma in his youth to become a college athlete, a successful rancher, and New York City Police Commissioner. Then he resigned his desk job as the Assistant Secretary of the Navy to endanger himself in battle. At least those parts of the story are true. The rest is not:

Roosevelt gives the impression that he alone was the first to charge the San Juan Heights to drive away the entrenched Spaniards. This image of Theodore Roosevelt was propagated with the help of Richard Harding Davis. Reporting for the New York Herald, Davis transcribed what Roosevelt told him, then added his own twist to the story. In addition to the newspaper articles, magazines and books picked up his story. Davis depicted a fearless Roosevelt, wearing a blue polka-dotted bandanna, charging up the hill mounted on his horse, Texas. Thus the legend of Theodore Roosevelt was created (Yockelson 1998, 2).

As he continued to recount his exploits, the tales grew taller and taller (Yockelson 1998, 2). Eventually, reflecting satisfactorily on his own bravery, Roosevelt wrote: “I am entitled to the Medal of Honor and I want it” (Yockelson 1998, 1). Four months later, he “painfully told [Senator Henry Cabot] Lodge on December 6 that ‘if I didn’t earn it, then no commissioned officer can ever earn it’” (Yockelson 1998, 3).

When faced with the lack of direct eyewitnesses to prove his valor, Roosevelt claimed that was because he was so far out ahead of his fellow soldiers: “I don’t know who saw me throughout the fight, because I was almost always in the front and could not tell who was close behind me, and was paying no attention to it” (Yockelson 1998, 4). His entitlement reached a fevered pitch when he wrote Senator Lodge: “I don’t ask this as a favor—I ask it as a right . . . If [the president and the War Department] want fighting [over it], they shall have it” (Yockelson 1998, 3).

Twenty-six other soldiers did earn the Congressional Medal of Honor in the fight for Santiago, Cuba, including the five Black cavalrymen of the 10th and the one sailor mentioned above, but Roosevelt did not receive the citation in his lifetime (Yockelson 1998, 4). He did not lose well, especially not to the African American soldiers that the War Department recognized:

In a series of articles published in Scribner’s Magazine [Roosevelt] contended that the physical ability of African-Americans to perform on the battlefield was only useful if guided by the paternal supervision of white officers. He even claimed that African-American soldiers had an inordinate tendency to retreat and engage in “misconduct” when white officers were not present. . . . [This behavior was] “natural in those but one generation from slavery and but a few generations removed from the wildest savagery” (Ngozi-Brown 1997, 44).

In another article, Roosevelt wrote that Black soldiers were “particularly dependent upon their white officers. Occasionally they produce non-commissioned officers who can take the initiative and accept responsibility precisely like the best class of whites; but this can not be expected normally, nor is it fair to expect it” (Amron 2012, 414-15). He even claimed that the African American soldiers lagged back in the rear, some fleeing the battlefield, until Roosevelt himself prompted them forward at revolver-point (Amron 2012, 415; New York State Division). “According to Presley Holliday, a former Sergeant in the 10th Cavalry, Roosevelt actually stopped four soldiers on their way to pick up ammunition from a supply point”—not retreating at all, in fact. The four soldiers were doing their job (New York State Division).

How did the United States War Department see fit to reject Roosevelt’s lobbying for an award and instead bestow the same upon a handful on the soldiers he disparaged? Could they have been swayed by other press outlets? J. N. Johnson, a prominent African American doctor and attorney, wrote to the Washington Post:

. . . I write to thank the press, including The Post, in the name of the whole race, for favorable mention of the black soldiers who played their part so well, though having no opportunity for official recognition of their conspicuous bravery. . . . The negro soldier was needed; he was on hand and played his part well; and though the government is silent the press sings his praise (“Negro Soldiers Bravery” 1898).

Unfortunately, according to antiracism expert Ibram X. Kendi in his book Stamped from the Beginning: The Definitive History of Racist Ideas in America, the recognition of these Black war heroes did little to halt the spread of racist ideas. “While ‘negative’ portrayals of Black people often reinforced racist ideas, ‘positive’ portrayals did not necessarily weaken racist ideas. The ‘positive’ portrayals could be dismissed as extraordinary Negroes, and the ‘negative’ portrayals could be generalized as typical” (2017, 328). Bravery, patriotism, and valor would not end discrimination. In fact, the crimes of the Jim Crow period—including disenfranchisement, convict leasing, and lynchings—would only accelerate.

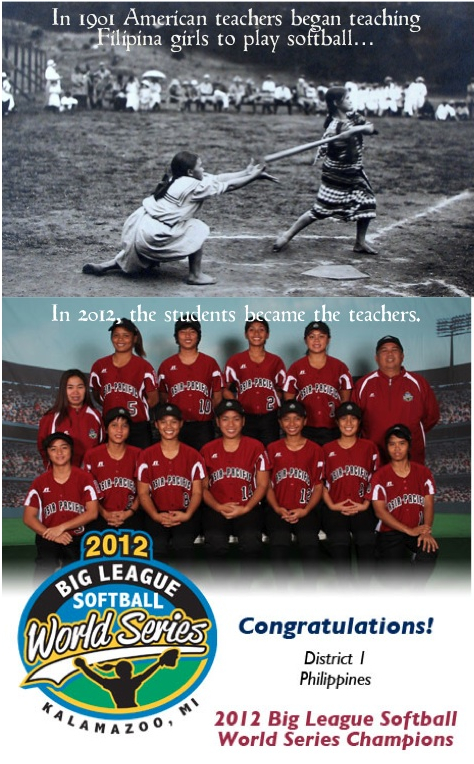

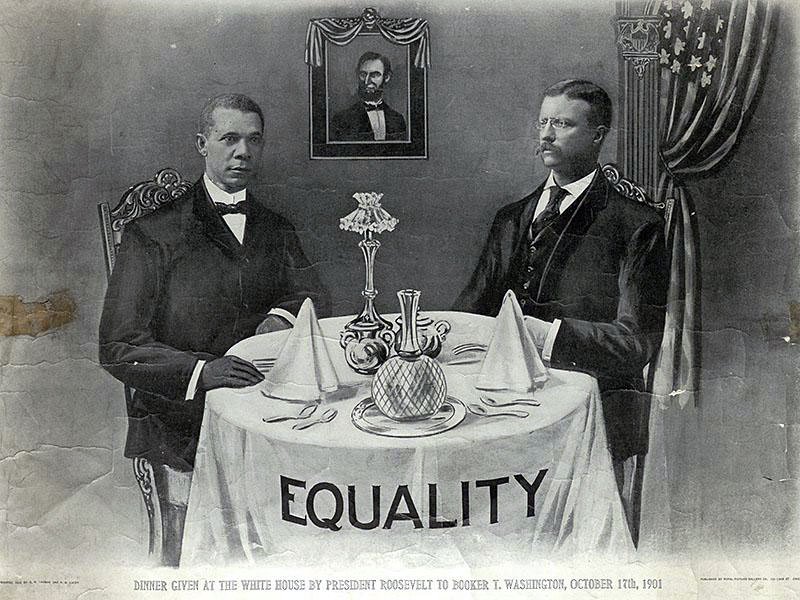

How bitter would Roosevelt be? On the one hand, in 1901 he was the first president to invite an African American to join his family for supper at the President’s House. But the straightforward invitation to prominent educator Booker T. Washington set off a firestorm. South Carolina senator said that it would take the lynchings of a thousand Black people “before they will learn their place again” (Kendi 2017, 290). Roosevelt promised to never repeat his mistake, and to be sure he officially renamed the residence the White House (Kendi 2017, 290).

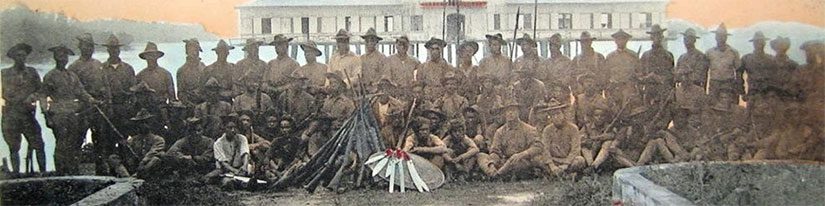

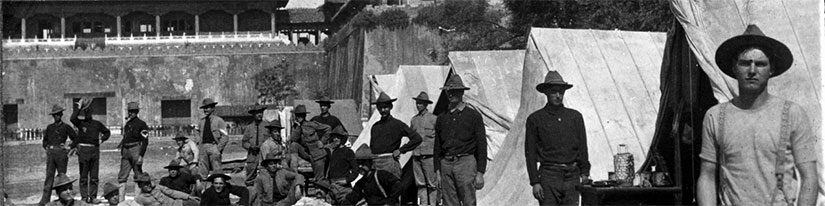

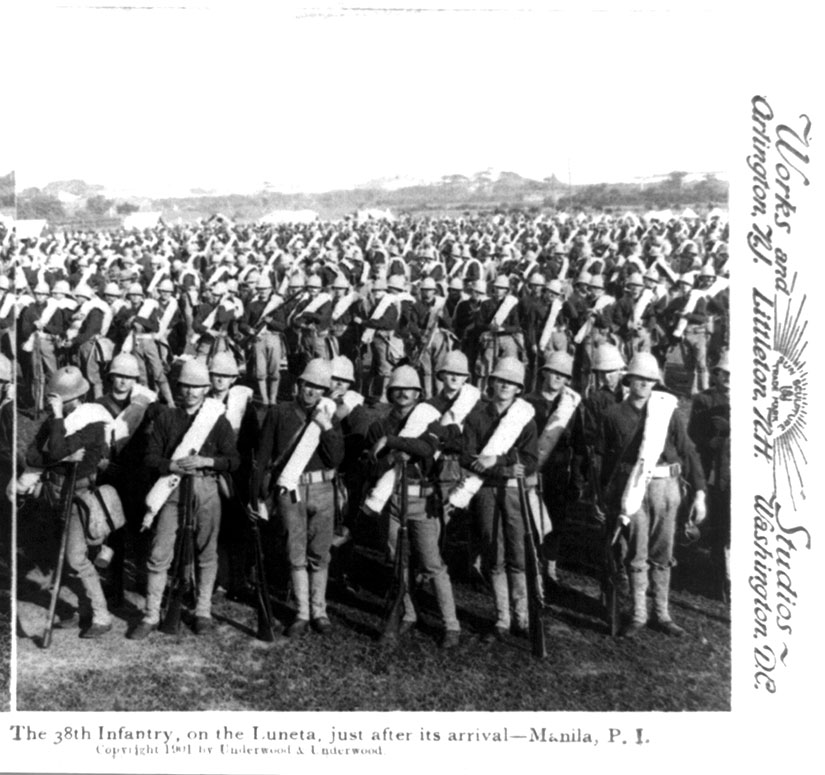

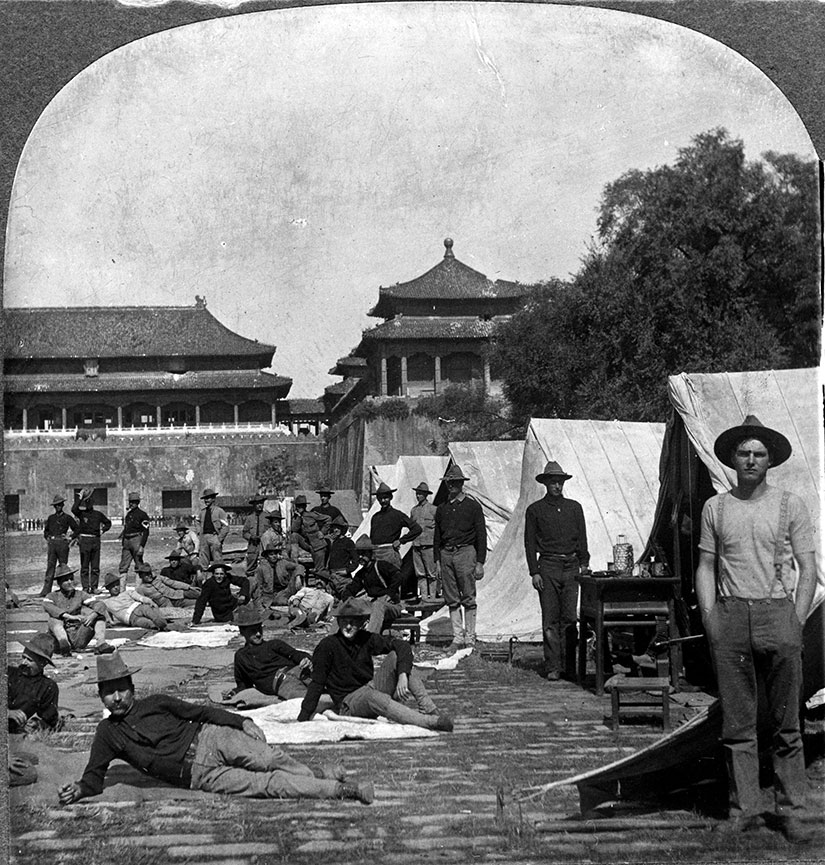

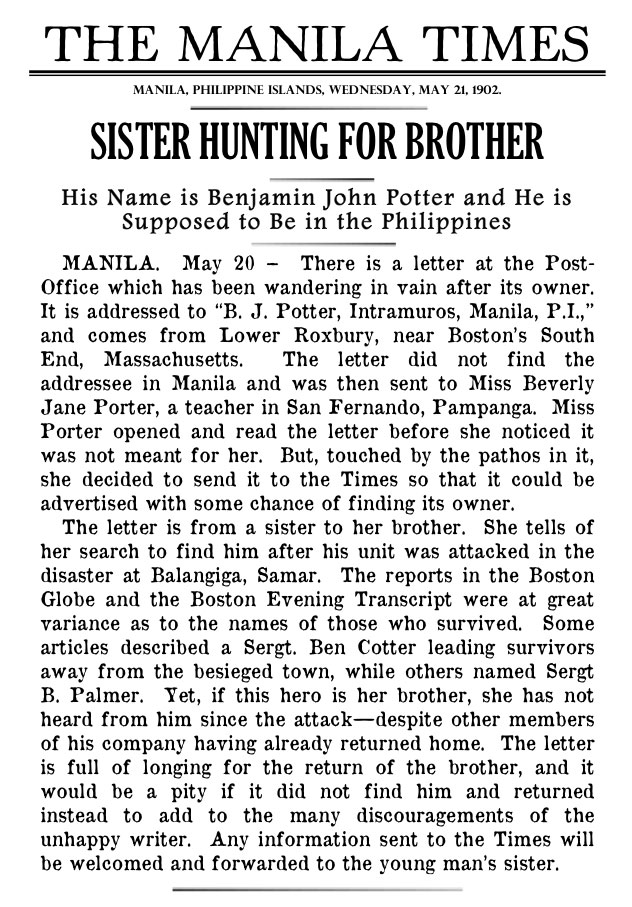

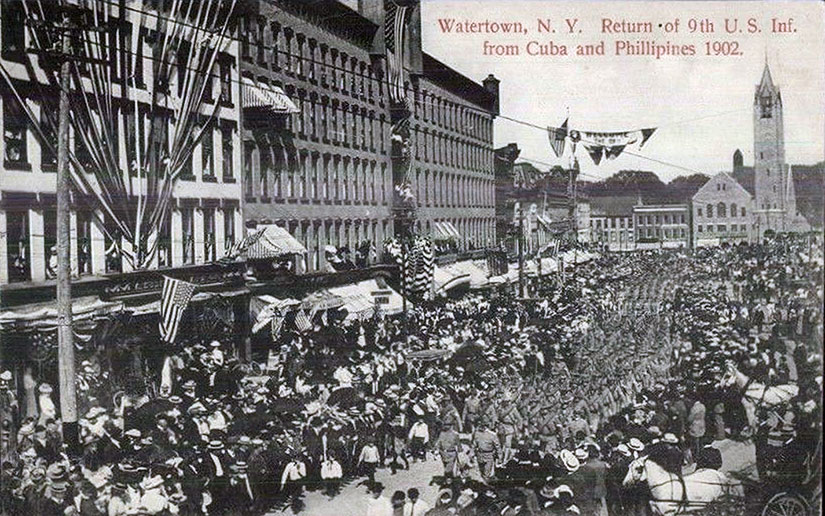

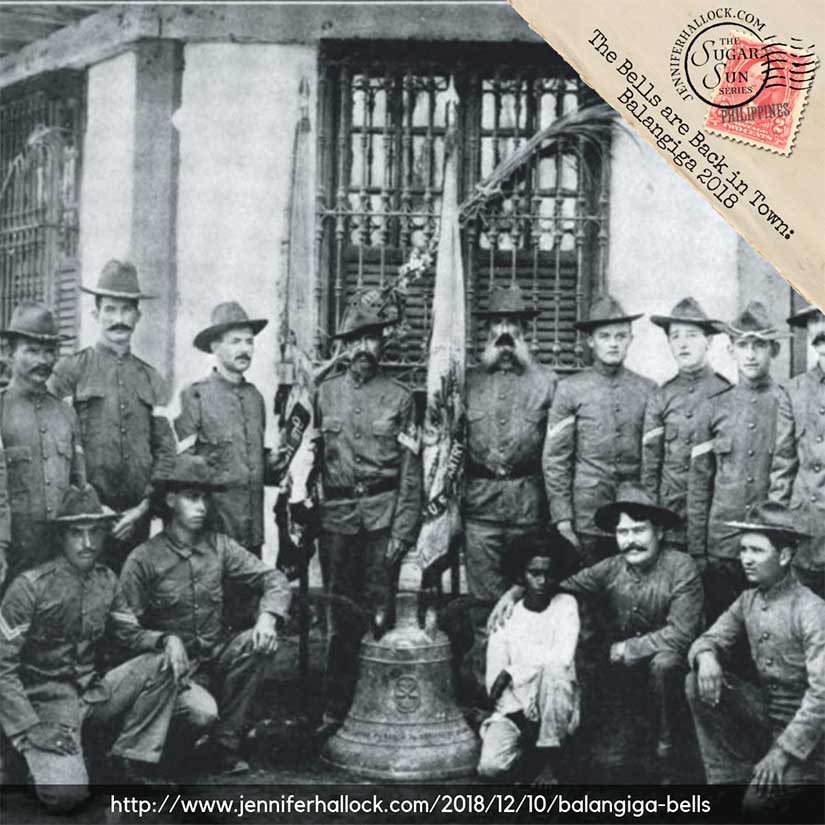

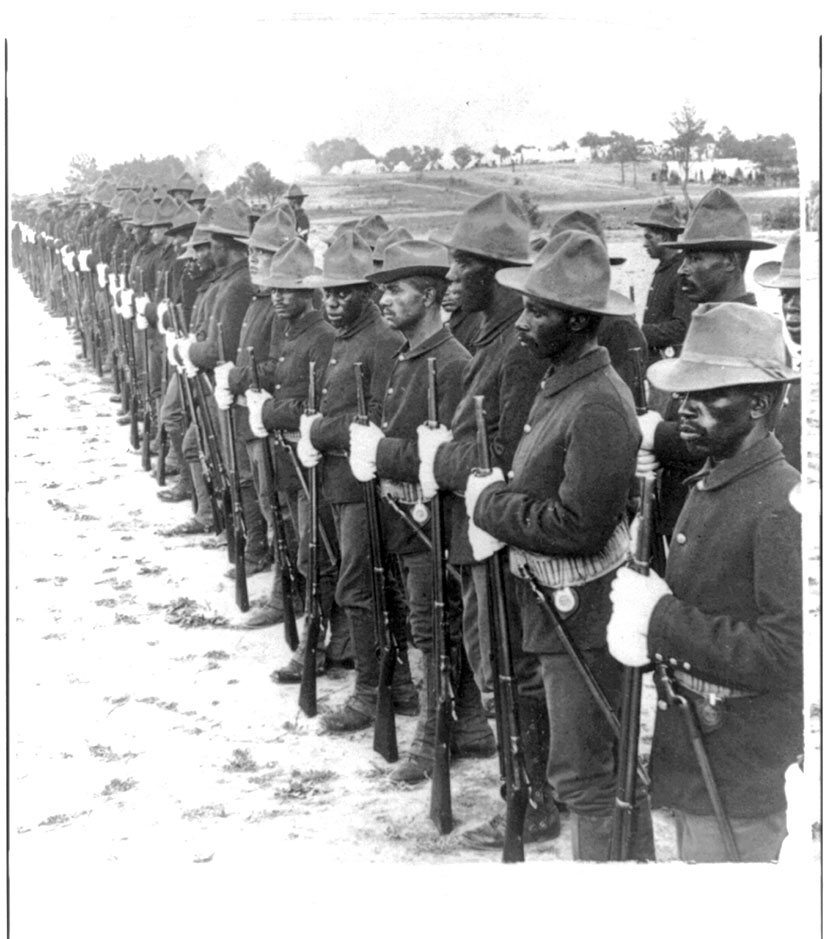

He would also single-handedly tear apart the careers and eliminate the pensions of 167 Black veterans—the entire 25th Infantry battalion—after blaming them for a riot in Brownsville, Texas, despite clear evidence to the contrary. Six of these men had won the Congressional Medal of Honor, and thirteen had received the Certificate of Merit, the next highest award. 123 of the 167 had served in the US Army for over five years, which means combat in the Philippines, and 26 of them had served for over ten years, which means combat in Cuba too. One career soldier had spent 24 years in the Army. All of them lost their entire retirement investment by executive order, without even the decency of a court-martial (“Troops Not Spared” 1906, 1). (Much the same had already happened to Sergeant Major John W. Calloway for equally spurious reasons.)

Eventually Teddy Roosevelt got what he wanted—in 2001, more than eight decades after his death. During the waning days of the Clinton Administration, the U.S. Department of Defense bestowed a posthumous Congressional Medal of Honor upon Theodore Roosevelt. His media machine finally won.

selected Bibliography:

[Featured image is a vintage postcard of the 25th Infantry at Basilan in the Sulu Archipelago.]

Amron, Andrew D. “Reinforcing Manliness: Black State Militias, the Spanish-American War, and the Image of the African-American Soldier, 1891-1900.” The Journal of African American History 97, no. 4 (2012): 401-26. https://doi.org/10.5323/jafriamerhist.97.4.0401.

“Colored Troops Win Praise from the White Press.” Richmond Planet. (Richmond, Va.), 23 July 1898. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress. https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn84025841/1898-07-23/ed-1/seq-2/.

“Compliment to Colored Soldiers.” Iowa State Bystander. (Des Moines, Iowa), 29 July 1898. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress. https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn83025186/1898-07-29/ed-1/seq-1/.

“Gov. Tanner’s Speech.” Richmond Planet. (Richmond, Va.), 23 July 1898. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress. https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn84025841/1898-07-23/ed-1/seq-4/.

Johnson, J. N. “Negro Soldiers’ Bravery: How Can They Be Utilized in Our New Territory.” The Washington Post (1877-1922), Jul 13, 1898. https://search.proquest.com/docview/143949611?accountid=11220.

Kendi, Ibram X. Stamped from the Beginning: The Definitive History of Racist Ideas in America. New York: Bold Type Books, 2017. Kindle edition.

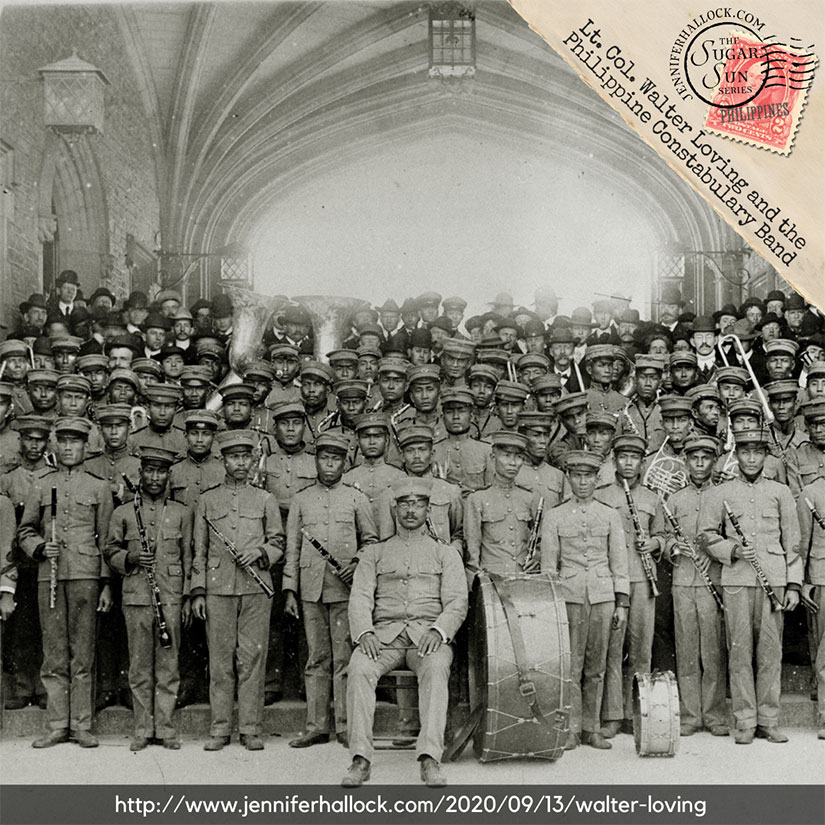

New York State Division of Military and Naval Affairs. “Black Americans in the US Military from the American Revolution to the Korean War: The Spanish American War and the Philippine Insurgency.” New York State Military History Museum and Veterans Research Center. Last modified March 30, 2006. Accessed June 29, 2020. https://dmna.ny.gov/historic/articles/blacksMilitary/BlacksMilitaryContents.htm.

Ngozi-Brown, Scot. “African-American Soldiers and Filipinos: Racial Imperialism, Jim Crow and Social Relations.” The Journal of Negro History 82, no. 1 (1997): 42-53. https://doi.org/10.2307/2717495.

“President McKinley and the Negro Soldiers.” The Broad Ax. (Salt Lake City, Utah), 22 July 1899. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress. https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn84024055/1899-07-22/ed-1/seq-1/.

“Troops Not Spared.” The Washington Post (1877-1922), Nov 22, 1906. https://search.proquest.com/docview/144648836?accountid=11220.

Yockelson, Mitchell. “‘I Am Entitled to the Medal of Honor and I Want It’: Theodore Roosevelt and His Quest for Glory.” Prologue, Spring 1998. Accessed July 30, 2020. https://www.archives.gov/publications/prologue/1998/spring/roosevelt-and-medal-of-honor-1.html.