In addition to an extensive list of memoirs, biographies, and research texts on medical history that I have read for background research on Sugar Communion, I have also spent a lot of time walking the dog and listening to podcasts. Here’s a photo of Wile E. and me on the way to the trail, just because:

My heroine, Dr. Elizabeth “Liddy” Shepherd, M.D., is one of many young women who became physicians or surgeons at the turn of the twentieth century. Many? Yeah! I mean, not a flood but enough to say that it was a viable career path for quite a few. In romance novels, the introduction of a female doctor character is often presented as something truly exceptional: “the only female physician in England,” one says, which is sorta lousy history. (Is it good marketing? I suppose so.) The aforementioned heroine was loosely based on the first female physician licensed in England, Elizabeth Garrett Anderson—not counting James Barry, who was assigned female at birth. By 1876, the year this other novel takes place, Dr. Anderson was already training female doctors by the class-full in the medical school she had opened—women who could have applied for licensure just like hers. Also, Scotland not England was really the “scene of the first major attempt by British women to break into the exclusively male world of medicine.”

Women in the US probably had an easier road, with several coeducational and women’s medical schools existing in the Gilded Age, especially in the midwest. At the University of Michigan, for example, women made up a quarter of the class. The school turned out country doctors—a difficult, smelly career that these Gibson girls were welcome to try. Michigan was a better school than most, but in general medical education was not really stellar for either men or women. For example, there were no written examinations at Harvard Medical School at the beginning of the Gilded Age. None. In fact, that would have been impossible, one professor complained, because half of his students “could barely write.”

During the Gilded Age, doctors went from being considered “butchers” and “bleeders” to people who could actually diagnose what was wrong with you. Obviously, this is a great advance—though, before antibiotics and safe anesthesia, odds on treatment, care, and recovery were still not great.

It was the improvement in the status of doctors that led conservative elements of American society to decide that medicine was not an appropriate career for women, often because a woman doctor would be taking a “good job” from a man. The publication of the Flexner Report in 1910 is credited with creating the modern scientific medical school system in the US, but it also directly or indirectly caused the closure of many medical schools for women and African Americans. Those that had been coeducational reduced their admission of women, partly because they had a rise in male applicants. One study calls an unintended consequence of Flexner’s report “the near elimination of women in the physician workforce between 1910 and 1970.” It is the post-Gilded Age lack of women in medicine that makes us think that women have always been uniformly shut out of the field.

(Side note: Johns Hopkins, the model of a modern medical school for Mr. Flexner, only managed to operate because of the patronage of four women: Martha Carey Thomas, Mary Elizabeth Garrett, Elizabeth King, and Mary Gwinn. According to Johns Hopkins: “They would raise the $500,000 needed to open the school and pay for a medical school building, but only if the school would open its doors to qualified women. Reluctantly, the men agreed.” Unfortunately, the legendary founder of internal medicine at Hopkins, Dr. William Osler, was less enthusiastic about the role of women in the field, and the numbers of female students would dwindle before growing again decades later.)

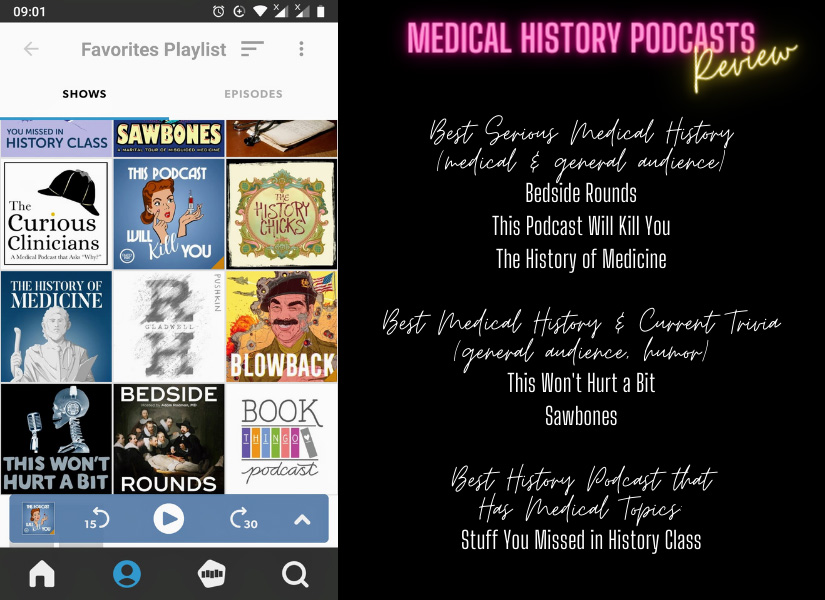

My character Liddy needs to be a good doctor, yet one appropriate to her time period. I had to understand the world of medicine she was a part of. Better than studying it, I had to immerse myself in it. For that task, I did use some good books, but mostly I listened to podcasts. Let’s talk about a few of those:

Bedside Rounds

I happened upon Bedside Rounds first and have since listened to every single episode. Dr. Adam Rodman is engaging and informative—so informative, in fact, that members of the American College of Physicians can earn Continuing Medical Education (CME) and Maintenance of Certification (MOC) credit for just listening to these episodes and taking a quick quiz! But, trust me, we general listeners need not worry about the test, nor are we left behind. Dr. Rodman’s intention was to model his podcast on Radio Lab, and his delivery is just as compelling and digestible (health-related pun?) as that popular program. There were times when I did backtrack 15 seconds or so just to let some point wash over me a second time, but keep in mind that I was taking mental notes for my book. A casual listener can easily stay on pace, though Rodman doesn’t shy away from the tough stuff. His presentations do have lighter moments but never get silly. Listening changes the way you view medicine, mostly by making you realize how young the field really is. (Note: The COVID-related episodes, including an in-depth treatment of previous coronaviruses and the 1918 flu, are very good.)

This podcast will kill you

Two immediate advantages of This Podcast Will Kill You are (1) the incredibly impressive epidemiologist-and-disease-ecologist-presenter-duo, Erin Welsh, Ph.D. and Erin Allmann Updyk, Ph.D.; and (2) the structure of each episode into separate segments on biology, history, and modern epidemiological issues related to each chosen disease. (They also have a Quarantini—or, if you prefer, a non-alcoholic Placeborita—for each episode, and this was before we were all quarantining.) “The Erins” (their label, though I prefer “Dr. Erins”) have just begun their fourth season, and that is a lot of episodes to catch up on, but you will be glad you did. Until I listened to TPWKY, I did not truly understand sickle cell disease, for example, or dengue—not even while I lived in the Philippines, which is embarrassing.

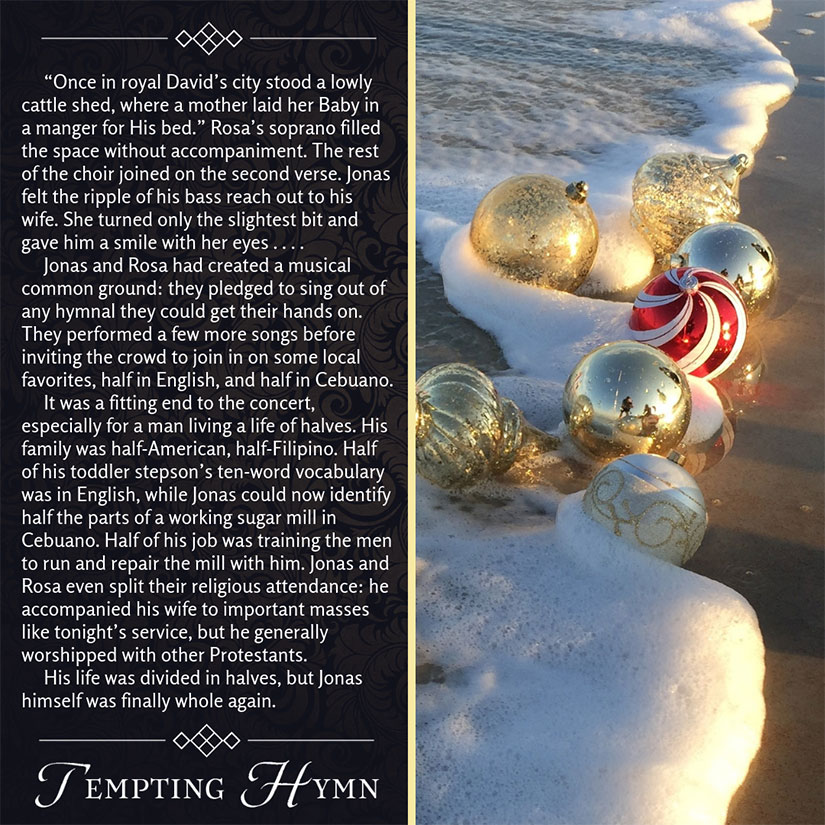

The Dr. Erins deal with diseases that other podcasts do not cover, like rinderpest, the bovine form of measles, which will have to be another glossary post on this blog because it comes up a few times in my books. (The Philippines lost 90% of their carabao population during the Philippine-American War period, which added greatly to the suffering of the people.) TPWKY also has episodes on cholera, malaria, and other diseases that have made an appearance in Under the Sugar Sun and, in particular, Tempting Hymn. Upcoming in Sugar Communion, TPWKY has been instrumental in my understanding of syphilis (don’t worry, I will stick to the chronotope), as well as smallpox and the history behind vaccines, aspirin, and caffeine. Relevant to the whole nineteenth and early twentieth century periods, there are episodes on typhoid fever and yellow fever and so much more! The more I listen, the more I love this podcast. I think they are having lots of (appropriate) fun too.

(Note: TPWKY also put out a series of excellent COVID episodes, as you might expect. They are broken down by different facets of the pandemic, along with a December 2020 update.)

the history of medicine

I have only listened to the first half of the first season of The History of Medicine podcast, but what I like about it is the deep dive into a narrative history of one big medical invention at a time. The first season is all about antibiotics—yay, penicillin! The show on plague (Yersinia pestis) is an excellent short backgrounder for all history teachers. A final advantage is that each episode here is very short. A possible disadvantage is that host and producer Kirby Gong is not a practicing physician—he only (ha!) has a master’s degree in biomedical engineering—but, actually, I call his perspective an advantage. He investigates medical inventions in a more procedural way. This podcast is the lens of an engineer, and I find that fascinating.

this won’t hurt a bit

This Won’t Hurt a Bit was a lot of fun, but sadly you will quickly run out of episodes. The two ER physicians who are the main hosts here, Dr. Mel Herbert and Dr. Jess Mason, are so busy with saving lives and producing other educational modules for ER docs that they are not actively creating many new releases. (Note: They do have a few COVID episodes that I have not gotten to yet. I am more interested in everything non-COVID right now. Go figure.) Though these doctors are not exclusively focused on history, usually each episode touches upon the historical approach to a disease or treatment in some way. They also teach you a lot about being a good patient, including when you might want to go to a hospital yourself! Dave Mason, Jess’s non-MD husband, is also one of the hosts, and he provides banter and asks the questions you really wanted to know. What I appreciate about Dave, though, is that he is not entirely silly, and he does not derail Mel and Jess when they are delivering information. This podcast is very well produced and engineered, with additional asides and definitions that you appreciate not dread.

sawbones

Sawbones is probably the most popular podcast of all the above, at least by the size of the live audiences that they have performed in front of (pre-quarantine days). This podcast is billed as “A Marital Tour of Misguided Medicine,” and that is because the show is based around the relationship of the medical host, Dr. Sydnee McElroy, and the comic relief, her husband Justin McElroy. (And they published a book too!) Most of the background medical history research is done by Sydnee—or maybe I’m underestimating Justin?—and fortunately she brings her A-game. Her episode on hydrotherapy was quite useful for my research. Dr. McElroy is also living and practicing in Huntington, W.V., which is where my grandparents and aunt lived (and therefore I spent a lot of time growing up)—and I feel connected to the McElroys that way too. (Surprise, surprise, they have several COVID episodes that I have not listened to yet, and they have also done an important set of podcasts on the history of medical racism inspired by recent protests.)

[Edited to add: The most recent episode on “Physician Burnout” is essential listening for all of us, physicians and patients alike. If you work in another “helper” profession, there are many parallels you will relate to.]

[just added!] maintenance phase

Maintenance Phase, a podcast that bills itself as “Wellness & weight loss, debunked & decoded,” started as a friend’s recommendation. She suggested the “Olestra” episode because I have family members who were involved in that indigestible chapter of history. This show has quickly become one of my favorites for general listening, though. I am one of those people who have been constantly in one diet cult or another my whole life, and counterprogramming is a challenge. The hosts of this podcast are not just scientifically informed, they are so much fun to listen to. In terms of medical history, their “Snake Oil” episode is one of my absolute favorites.

[just added!] the curious clinicians

The Curious Clinicians is sometimes too much for me, the writer who had not taken biology since freshman year in high school. This podcast is hosted by doctors and lab researchers for a similar audience, and so they do not explain every term or concept for the non-biologists in the room, and I recommend that we humanities folk out here choose our episodes wisely—but not shy away altogether. One episode that is amazing for everyone, especially if you are a foodie, is: “Episode 9: Why is umami so delicious?” A runner-up is “Episode 4: Why did Van Gogh paint with so much yellow?” Currently, I am learning about how fevers are actually useful, which is why almost all animals and even plants use them to fight infections!

stuff you missed in history class

For a history podcast, Stuff You Missed in History Class touches on medical topics a lot. There is even a good episode on the Flexner report, mentioned above. I think this is because the hosts, Holly Frey and Tracy Wilson, show a real concern for the daily lives of past people. One of their other stand-out episodes for me was on the “Orphan Trains,” which is a footnote of history you might also see in Sugar Communion. [Update: I don’t know anymore. I have to do a lot of cutting.] There is a deep backlog that I plan to dive into once I’m finished with some of my medical questions.

the others you see on my player

There are more podcasts that I have not yet gotten around to, like the History Chicks, the Revisionist History podcast, and This Land. Other titles are related to my professional interests. I highly, highly recommend the first season of Blowback about the Iraq War. I do not think that I can say that enough times. There are other podcasts in my favorites that I have listened only to a few episodes of, like Casenotes. (Nope, not the true-crime podcast, but the medical history one. It is a fortnightly podcast from the Physicians’ Gallery at the Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh. Essentially it is just the audio of lectures given by doctors and epidemiologists for other highly-degreed people. It can be very good, depending on the speaker, but it is like listening to a conference, not a highly-produced podcast.)

You may have also noticed Book Thingo on my Stitcher account because it’s the best romance podcast out there, and I’m not just saying that because they were willing to talk to me. Kat Mayo is also the originator of the #UndressAndres hashtag, so I owe her a lot. [Edited to add: Did you know I was interviewed for a podcast on Balangiga too? Check it out!]

If you know of more stuff I should be listening to—especially anything relevant to Sugar Communion—please let me know. My dog always needs walking.