I spent the last two weeks of February on an amazing trip to the Philippines. Packing everyone I wanted to see into 14 days—plus romance events!—was a little insane, but I made the most of every minute.

I started the business end of things with an appearance at the Philippine Romance Convention 2017, hosted by the Romance Writers of the Philippines at Alabang Town Center—a mall that happens to be my old stomping grounds. I was honored to sit on the Steamy Romance Panel with Mina V. Esguerra, Georgette S. Gonzales, and Bianca Mori. These are three outstanding authors. Mina’s Iris After the Incident is such an important, sex-positive, feminist contemporary romance that I wrote a whole blog post about it. Georgette writes intense romantic suspense that tackles politics, corruption, and more. And Bianca’s globe-trotting romantic suspense Takedown trilogy is like a cocktail of Ocean’s 11 and Mr. and Mrs. Smith, but with more sex. It goes without saying that this was an amazing evening.

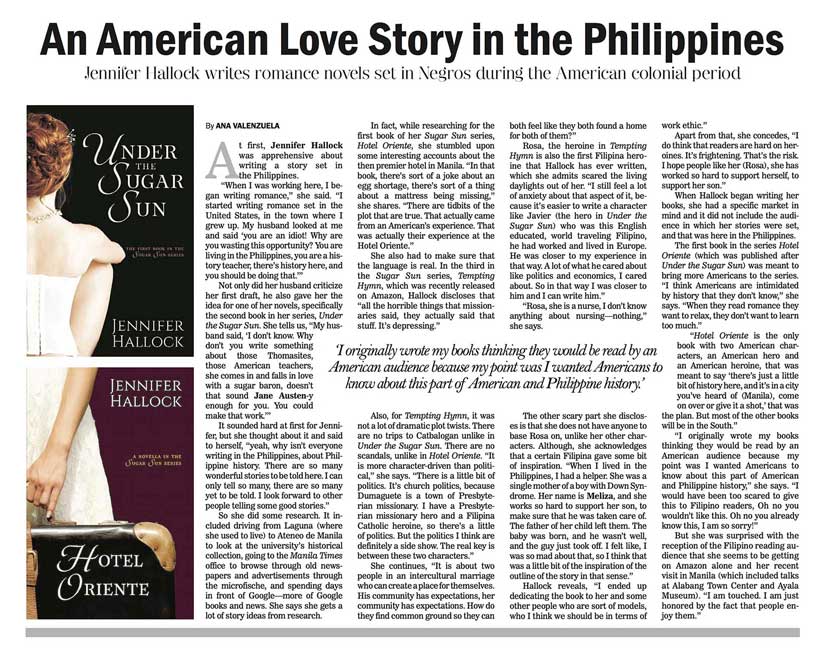

While I was there, author Ana Valenzuela and I grabbed a coffee at Starbuck’s so we could chat. That chat eventually turned into this hugely flattering article in the Manila Bulletin, the leading broadsheet newspaper in the Philippines.

But I’m getting ahead of myself. Before that came out, I was able to do some awesome traveling that provided me inspiration for both my current Sugar Sun series and my anticipated second generation series, which will be set during World War II. I headed to Corregidor with three great friends: my amazing hostess and great friend, Regine; my former student and now accomplished Osprey pilot, Ginger; and Ginger’s husband, Tread, also an Osprey pilot.

Even though I have been to the island several times, even staying the night before, I find each return trip gives me new ideas. I pick up different tidbits on the tour every time. This time, in the Malinta Tunnel, I heard about the crazy parties the Americans threw at the very end, when they expected to be defeated any day. They needed to consume their supplies before the Japanese arrived, and they really needed to get out of that tunnel at night. What happened under the stars, on the beach, when no one was watching? Yep, that is romance material, if I’ve ever heard it. A celebration of life in the midst of death.

Only a few days later, I was on the other side of the channel, on the Bataan Peninsula. This, of course, is the site of the infamous Bataan Death March, where 76,000 Filipino and American soldiers were force marched over 100km without food or water. Tens of thousands died. This is not good romance novel material. But each marker we passed was a reminder of the sacrifice of others who came before.

Regine and I had gone to Bataan to see some even older history—particularly the heritage homes being preserved at Las Casas Filipinas de Acuzar. On the one hand, I loved this place. It is a resort made up of bahay na batos, bought and moved from all over the Philippines. And, with no other cities or villages in sight, you can almost imagine that this is what Manila looked like during the time of the Sugar Sun series—if you squint your eyes to avoid seeing the ATM machine hidden in the bottom floor of one of the houses. The guides are informative, and the location by the sea is breathtaking. And, if given the choice between having a house moved here and letting it deteriorate or be bulldozed, then the choice seems obvious. With all these homes in one place, a person can truly appreciate the proud architectural tradition of the islands.

However, there are down sides, too. First, these homes are not in their original context, to be appreciated by those who have some claim over their heritage. They are also glorified hotel rooms, rented out for exorbitant prices by the park’s creator. Unlike a national museum, this park is for profit, and it is not cheap to get to, nor stay at. Therefore, the history of the Philippines cannot be equally shared among all Filipinos. Also, the location by the sea is questionable because the salty air will accelerate deterioration. Finally, there are a dozen building projects going on at a time, and meanwhile those already built or moved are degrading. It feels a little like a resort built by someone with ADHD—once one thing is halfway done, it gets pushed aside for a shiny new toy.

But, it is beautiful. And I got to see a recreation of the Hotel de Oriente! I felt like I should be giving out copies of my novella at the door—but, alas, I did not have any with me. The building looked accurate on the outside, but there are no surviving photos of the inside, so they have improvised. And while I applaud them hiring all local craftsmen to do the ornate inlaid woodwork, this interior makes the a Baroque palace look minimalist. Still, I was thrilled to be there. It was a huge rush.

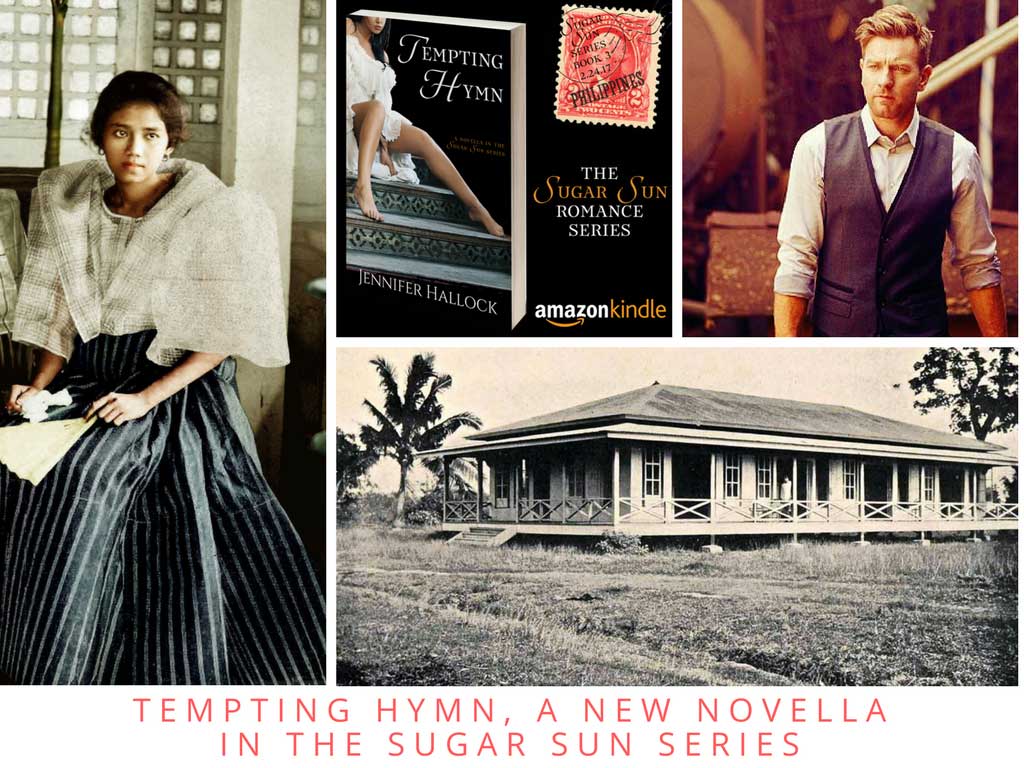

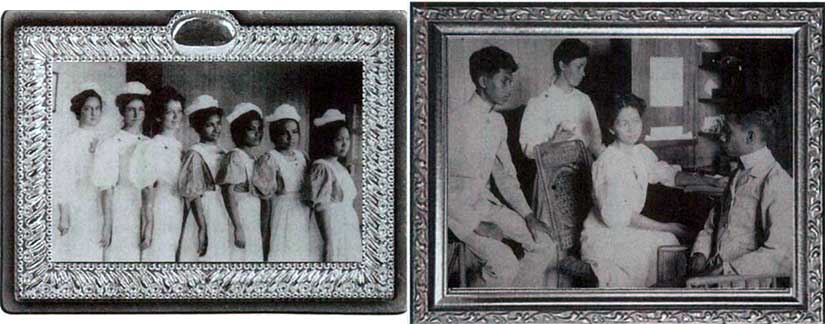

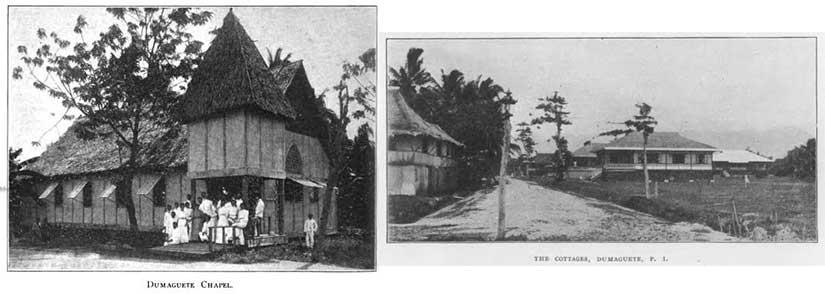

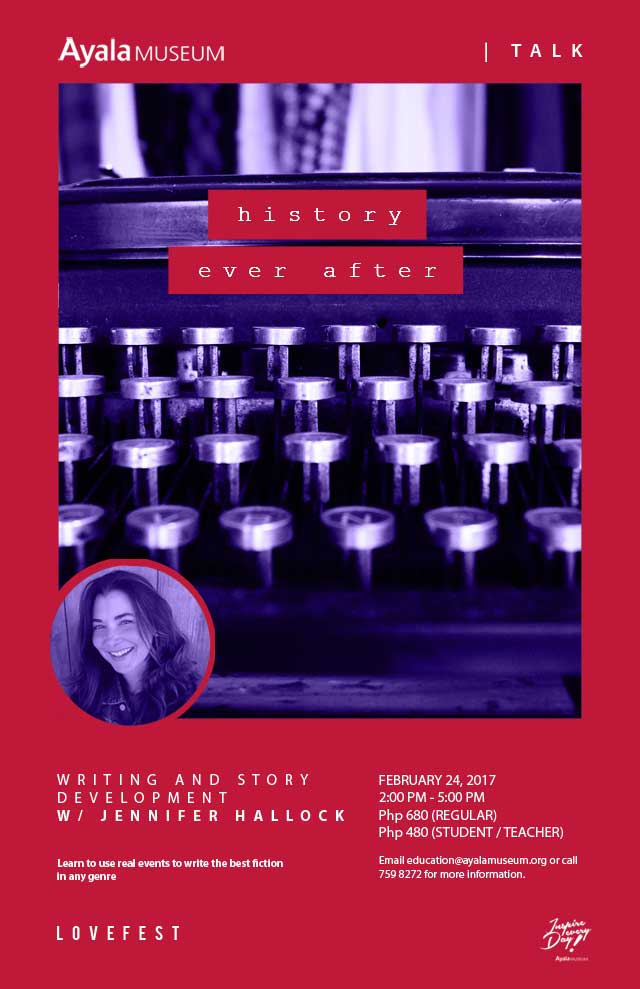

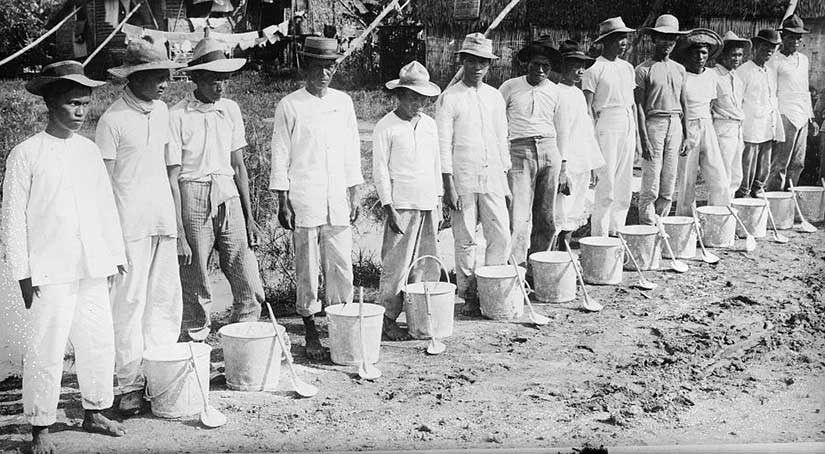

These amazing trips led up to the big event: the combined lecture of “History Ever After” at the Ayala Museum and the release of Tempting Hymn! It was such an amazing day. I talked for an hour about the history of the American colonial period, the Philippine-American War, and the Balangiga Incident. I wove in information about all my characters, even showing character boards with the casting of famous movie stars in the roles of each hero and heroine. (Piolo Pascual as Padre Andrés Gabiana was a special favorite.) I gave some special attention to the new novella, and then I signed and sold all the books I had brought with me. (One whole piece of checked baggage was just books!)

What a fantastic day, and I have to thank the whole #romanceclass crowd for coming out. You guys were amazing! Thanks to Mina Esguerra and Marjorie de Asis-Villaflores organizing the event. It would not have been possible without you. And thank you to my wonderful friend Regine, my advisor, therapist, and accountant—as well as the best hostess ever.

Regine and I spent my last evening in Manila at Intramuros at the 8th Annual Manila Transitio Festival commemorating the 100,000 dead in the Battle of Manila, 1945. Under the leadership of performer and popular historian extraordinaire, Carlos Celdran, we made wishes on the walls of Intramuros, listened to great music, ate great food, and even drank some buko (young coconut) vodka. Yum.

While much of this trip was devoted to writing, one of the truly best parts of being back was seeing my wonderful friends again, including people who have known my husband and me for over 20 years. The Philippines are beautiful, but it is the people who make this place so unforgettable. The fact that two of these people, Ben and Derek, now own three of the best bars in Manila doesn’t hurt, either!

Amazingly, I survived this whirlwind trip, but it only made me anxious for more. I cannot wait to go back. I need to write more books to justify the next trip, so off I go to write, write, write…!