Front Page News

On May 15th my good friend Ellen H. Reed sent me this article from the Manchester Union-Leader. (By the way, Ellen is a terrific historical and paranormal fiction author for everyone from middle-grade readers to adults.) Now Ellen knew I would be interested in the story because she recognized the island and battle that these students were investigating from the raw passages of a novel that I had been reading to her since 2017 at our Weare Area Writers Guild meetings.

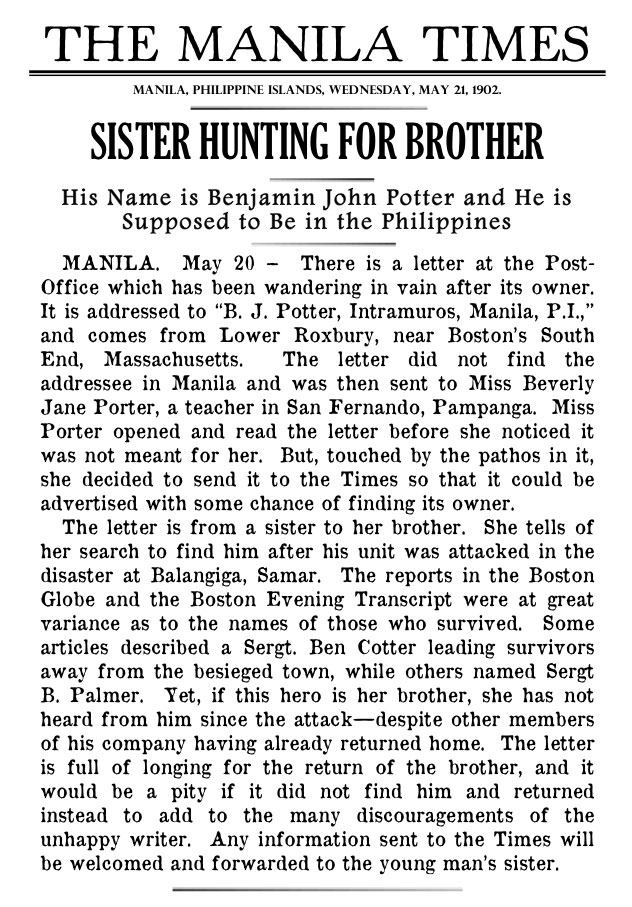

For years I have been digging into the history that too few Americans understand: I teach about Balangiga in one of my classes, I have blogged about it, written some more, and even been interviewed on podcasts. What happened there, if properly understood, could have warned us off tragedies at My Lai and Fallujah—maybe. Forgotten history helps no one, so I made this event the backstory of my character Ben Potter in Sugar Moon. (For even more of the history behind the novel, check out this list of posts.)

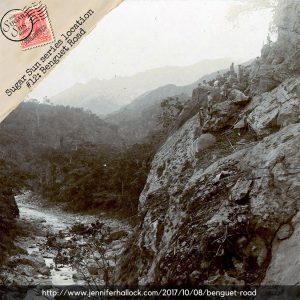

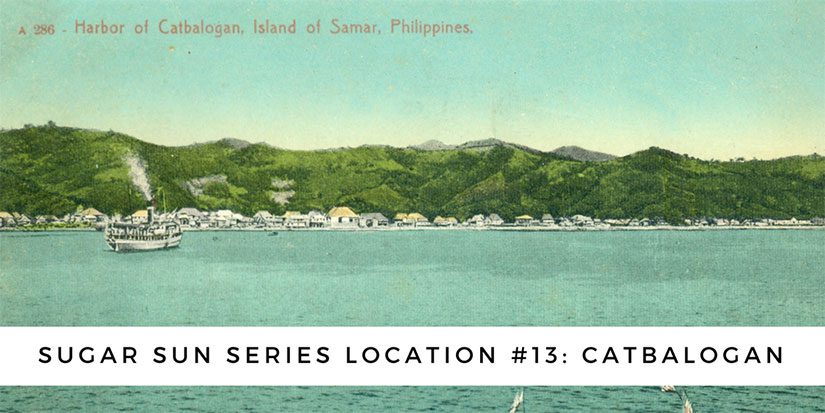

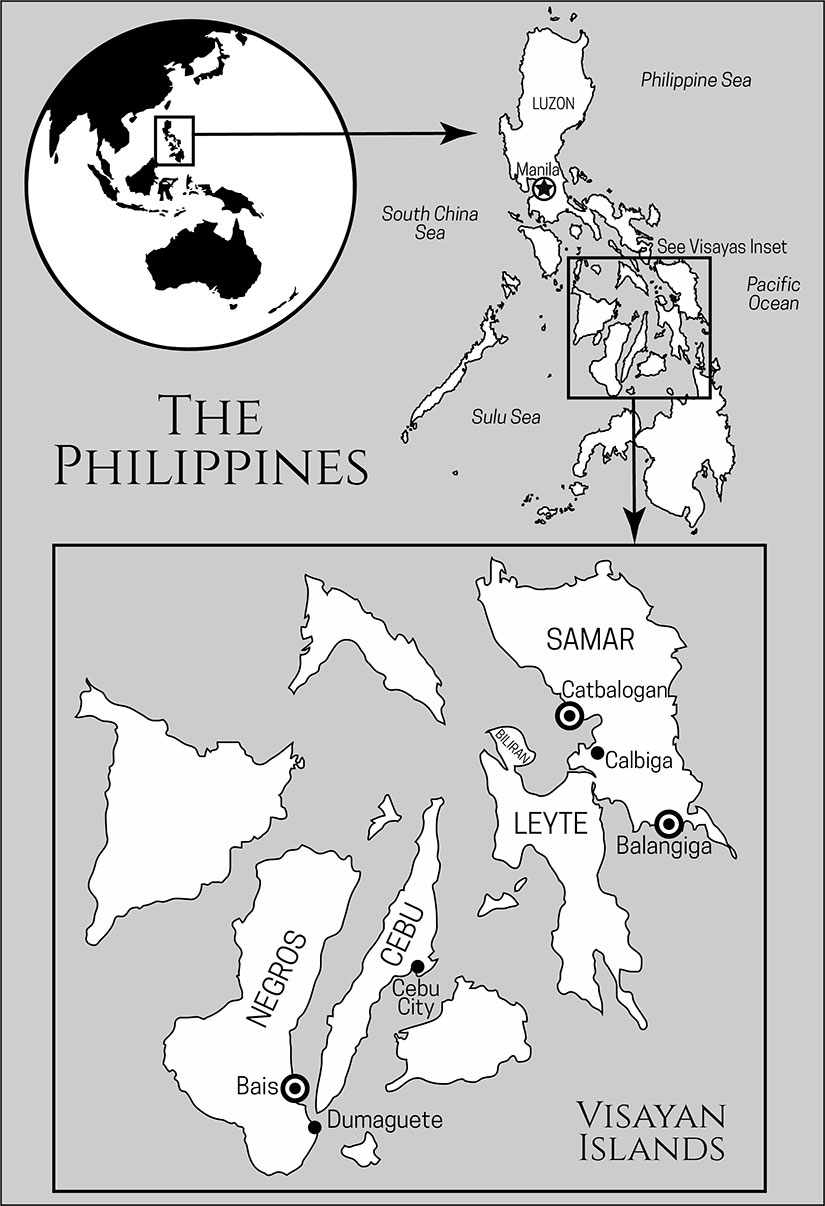

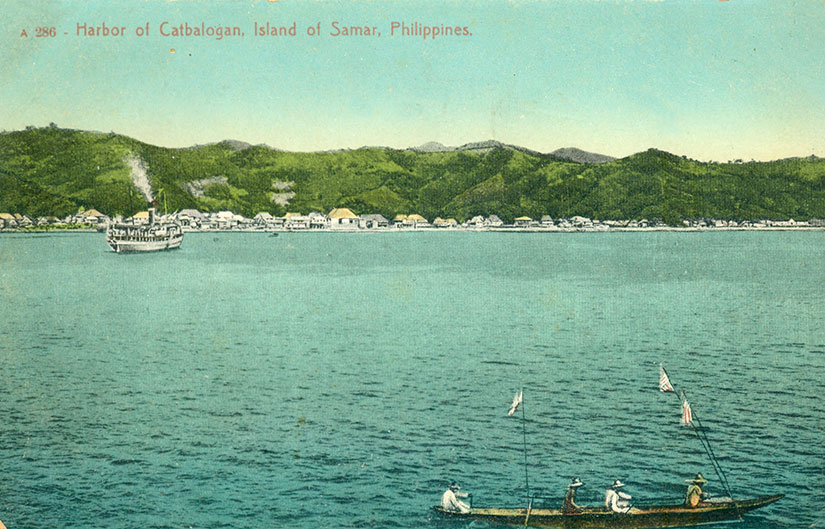

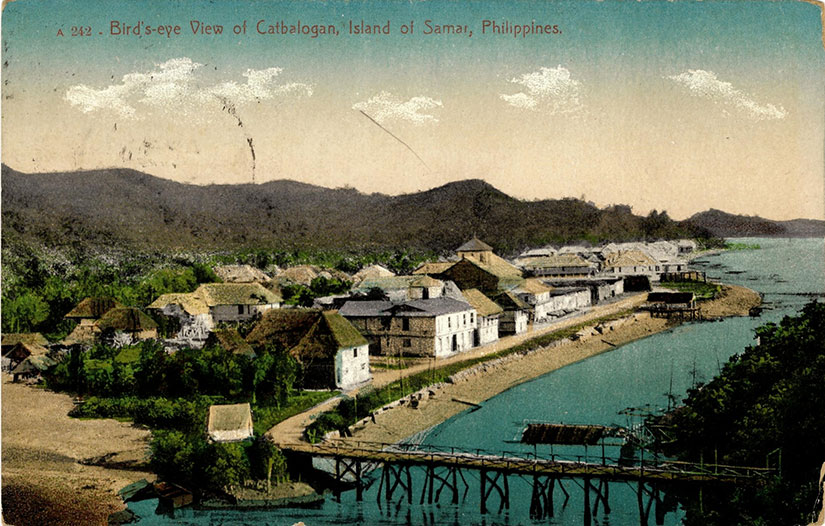

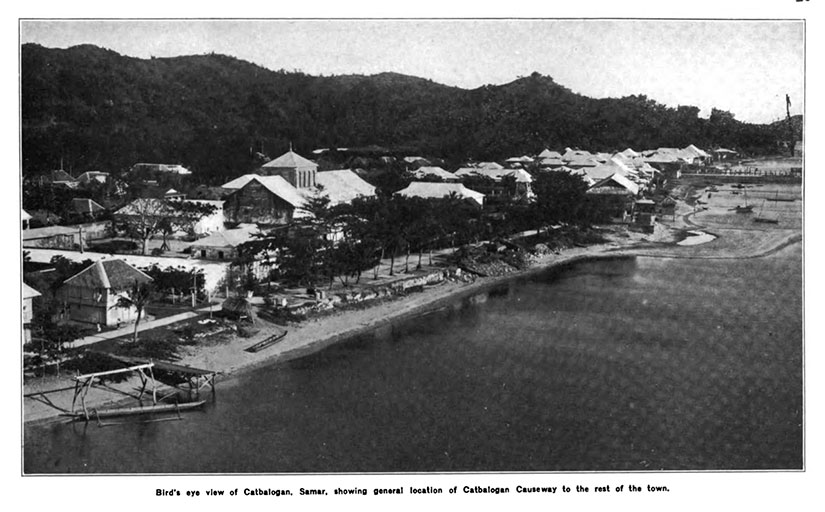

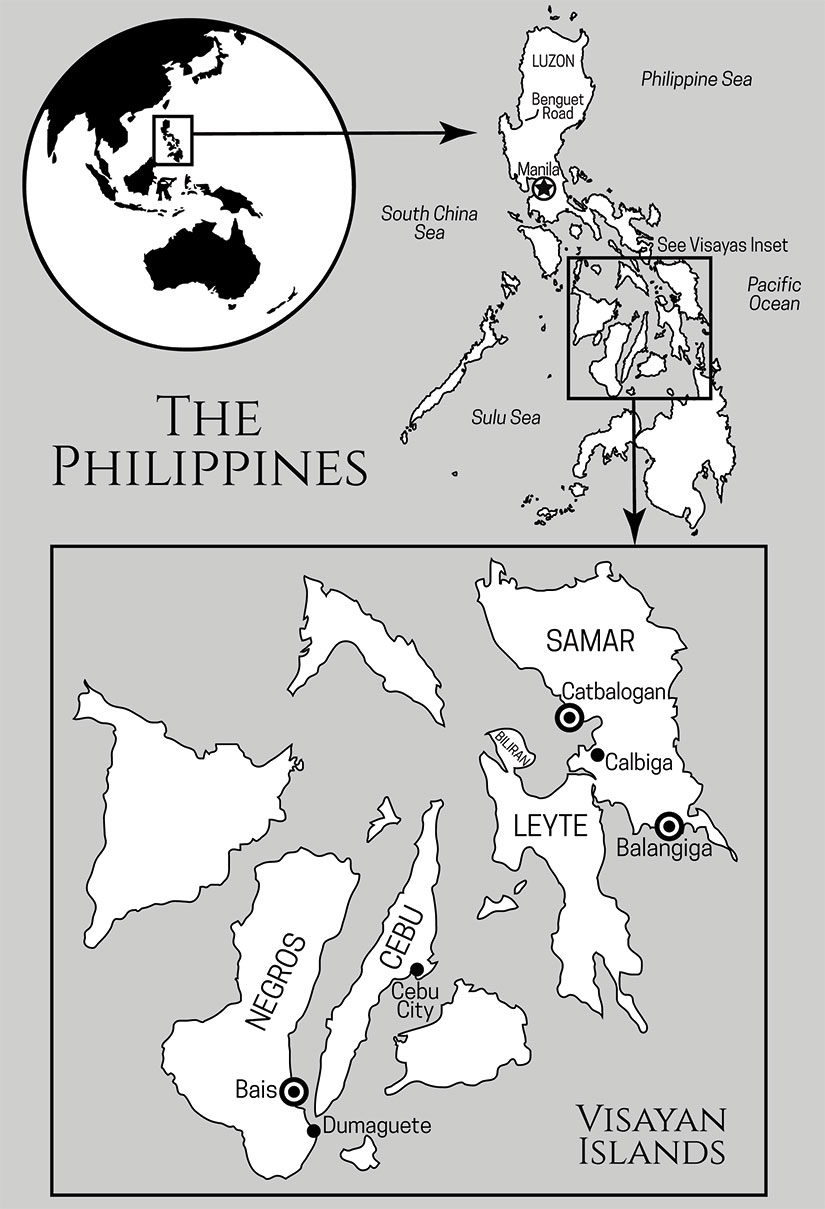

Research Tourism in the Philippines

I was so interested in investigating what happened at Balangiga that I dragged my husband down to Samar to see the town for ourselves. It was a quick trip, unfortunately, because torrential rains were causing mudslides, and we had to evacuate. (Note to self: Next time remember that different islands have different rainy seasons. Rookie mistake.) Because we could not get a flight out, we took a twenty-six-hour bus ride back on a urine-soaked back bench seat—the last two seats available, and with good reason. By the time we squeezed into a tric to get from the bus station to the airport parking lot, the eau de diesel of Manila bus traffic might as well have been the scent of daisies.

The image below is still one of my favorite pictures of the two of us from our life together in the Philippines. We moved back to the United States in 2011.

Artifacts closer to home

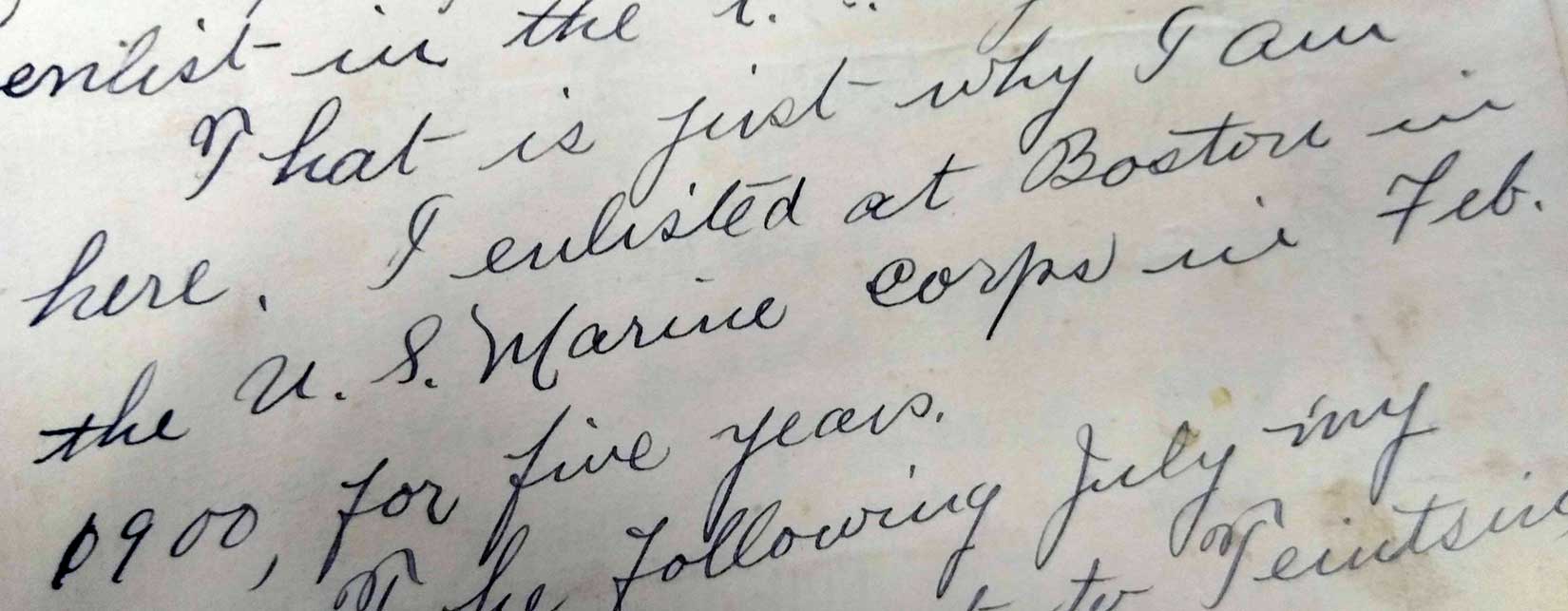

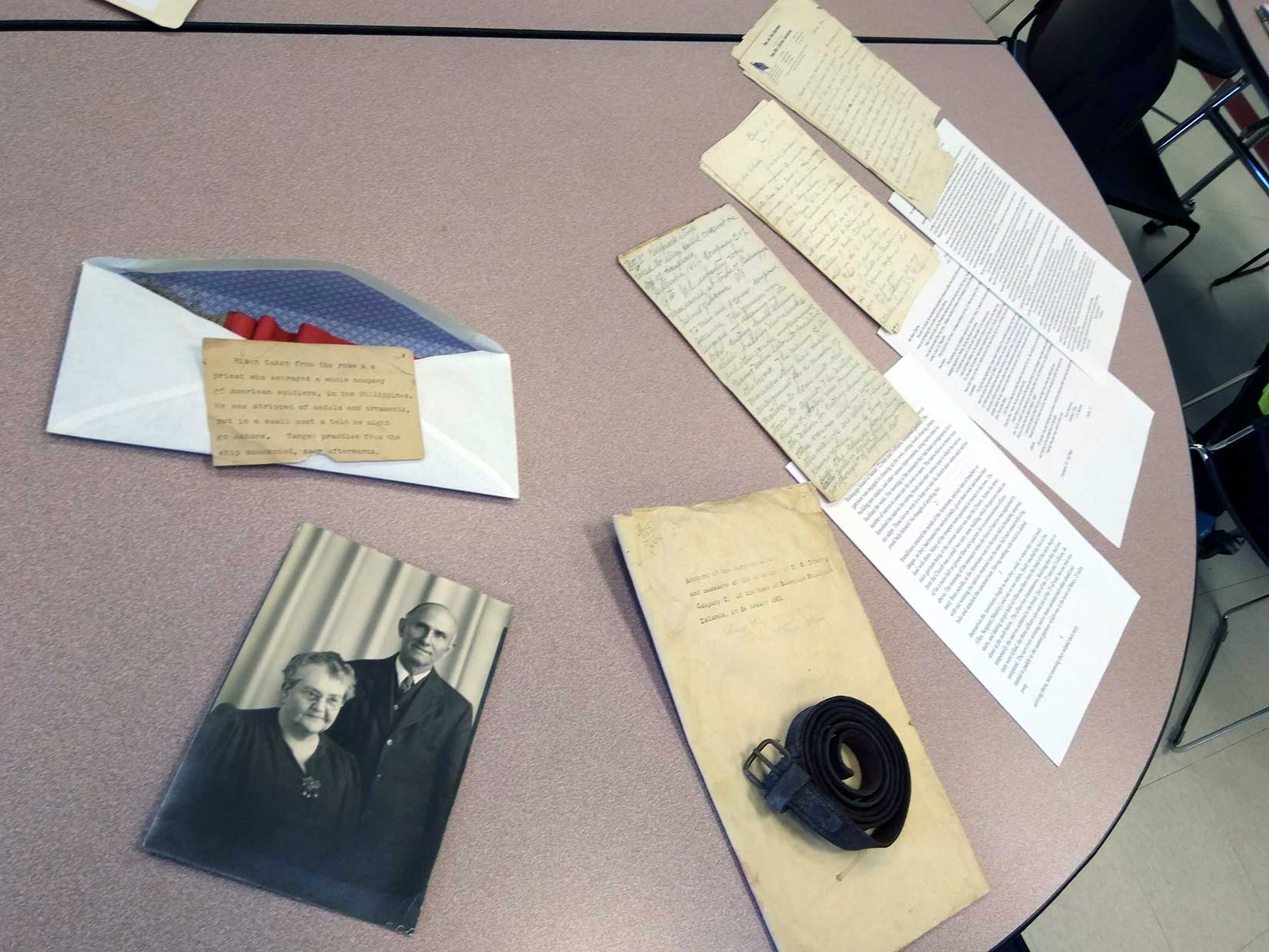

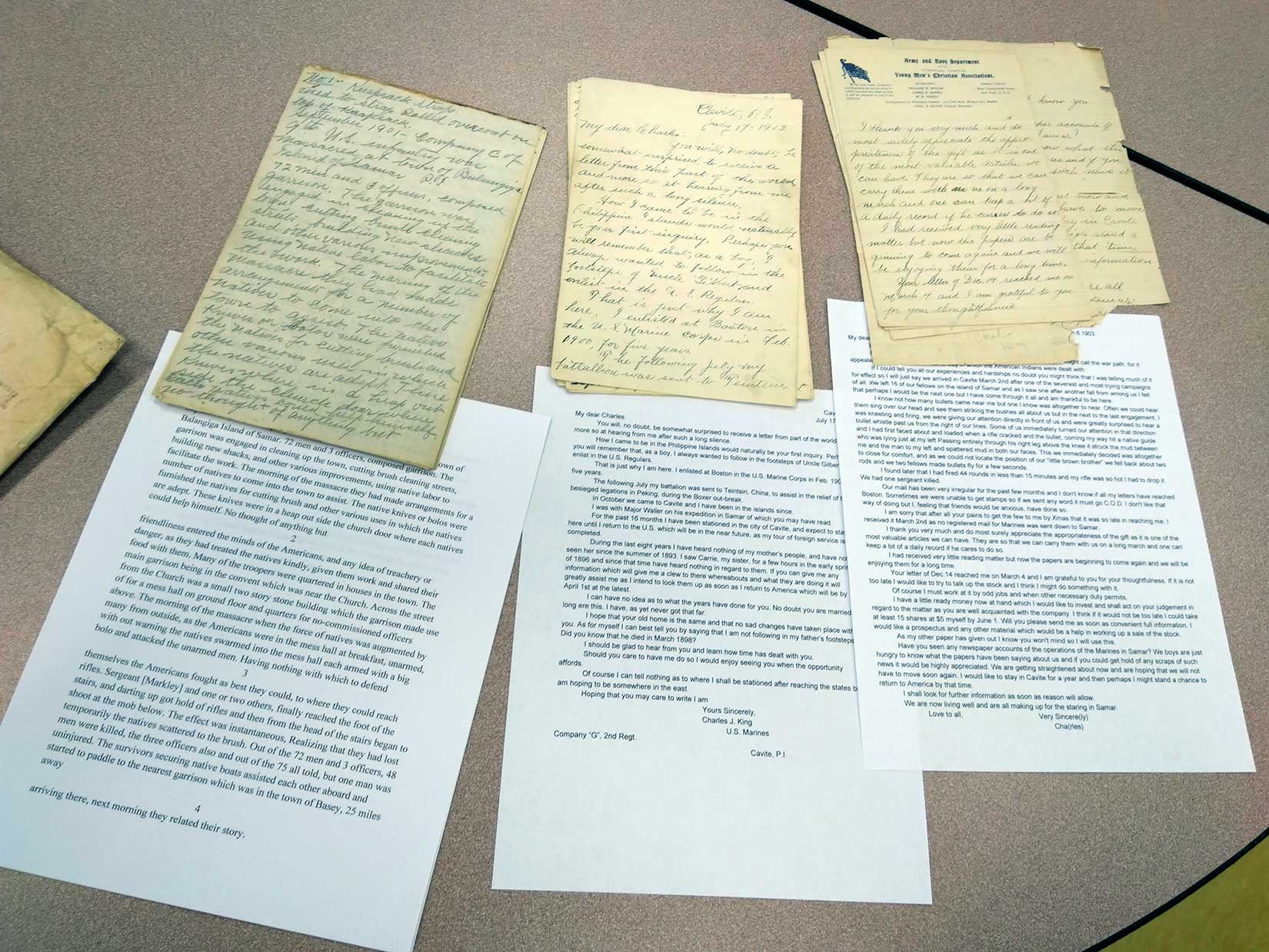

Imagine my surprise ten years later, when a few young historians uncovered new artifacts from Balangiga—in neighboring Derry, New Hampshire! These 8th- and 9th-grade students had become the caretakers of some letters, a leather strap, and a mysterious red sash—all artifacts that had been passed down from their original owner, Charles King, an American Marine from Amherst, Massachusetts. (The article said he was part of the Army, but his letter says otherwise.)

Because King had no children, he left the belongings to a nephew, who in turn gifted them to a man with a passion for history, T.J. Cullinane of the Derry Heritage Commission. Cullinane offered them to teachers Erin Gagliardi and Sue Gauthier. And Erin and Sue showed them to their history enrichment group, a non-credit activity for volunteer students at St. Thomas Aquinas School.

The pandemic shut down their school, but they kept working on the project—all the more earnestly because they did not have the typical distractions of busy school life and classes. They transcribed the letters and started to learn about a campaign of retribution that troubled them.

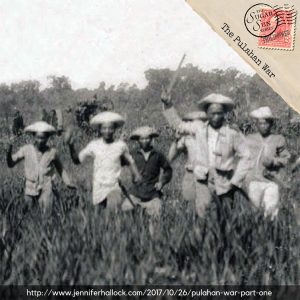

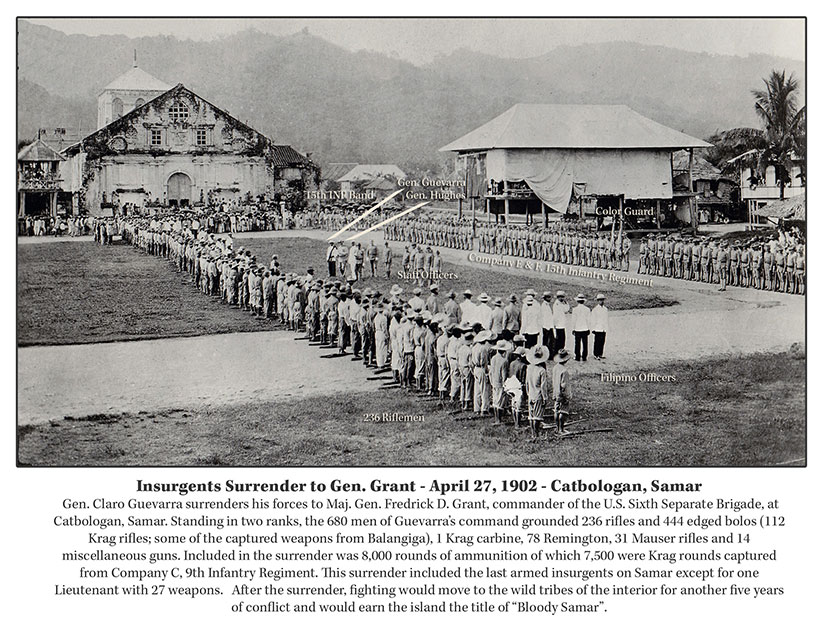

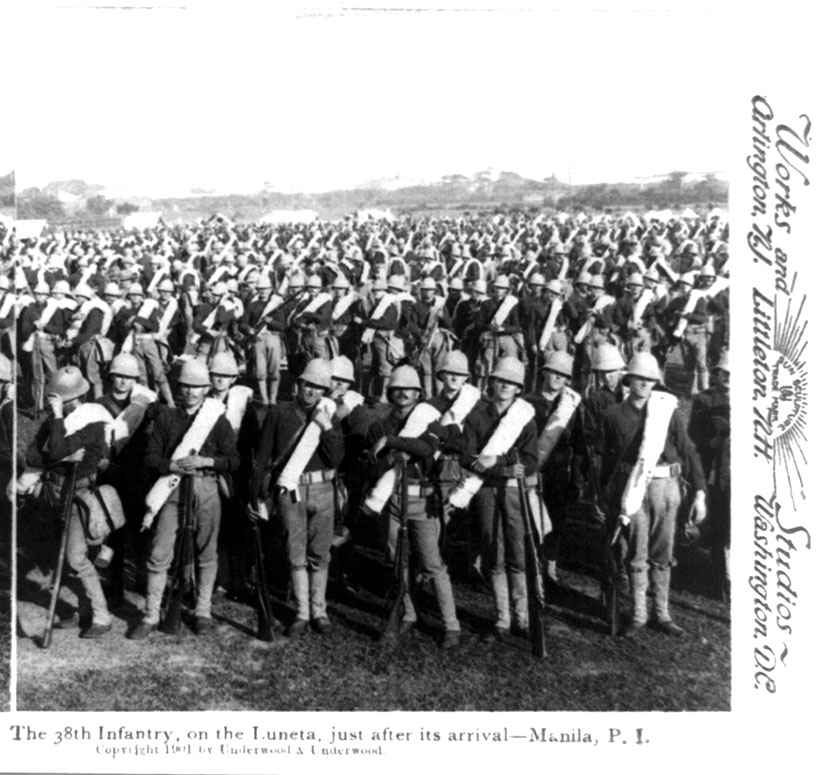

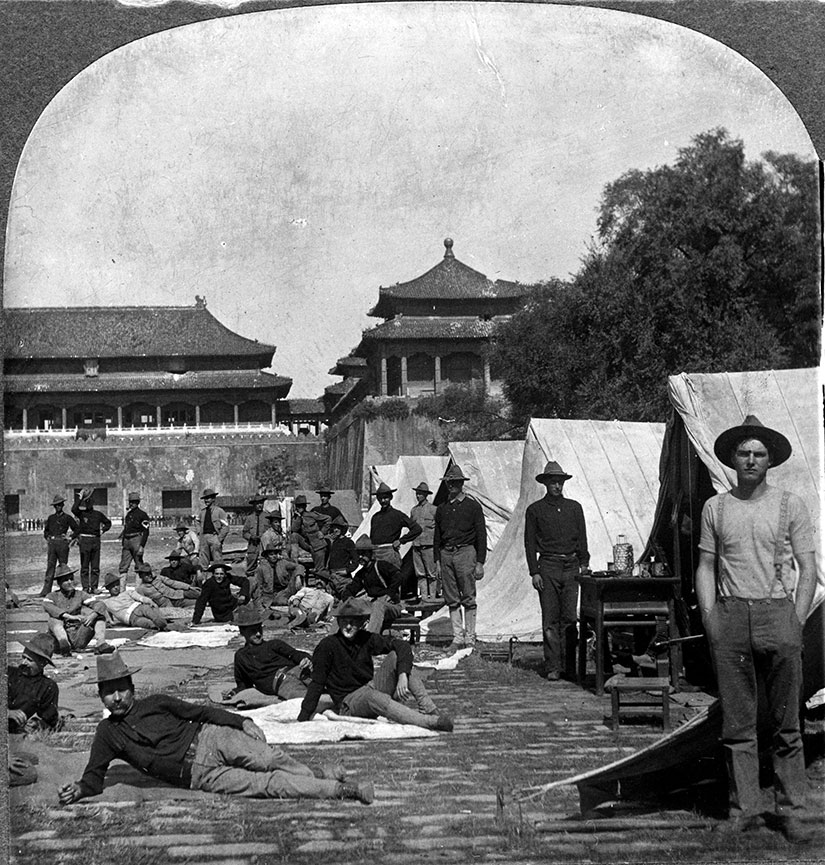

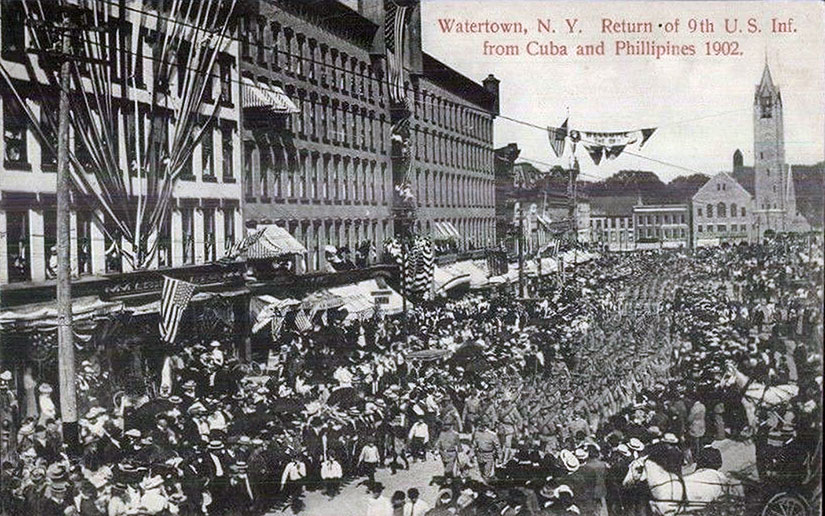

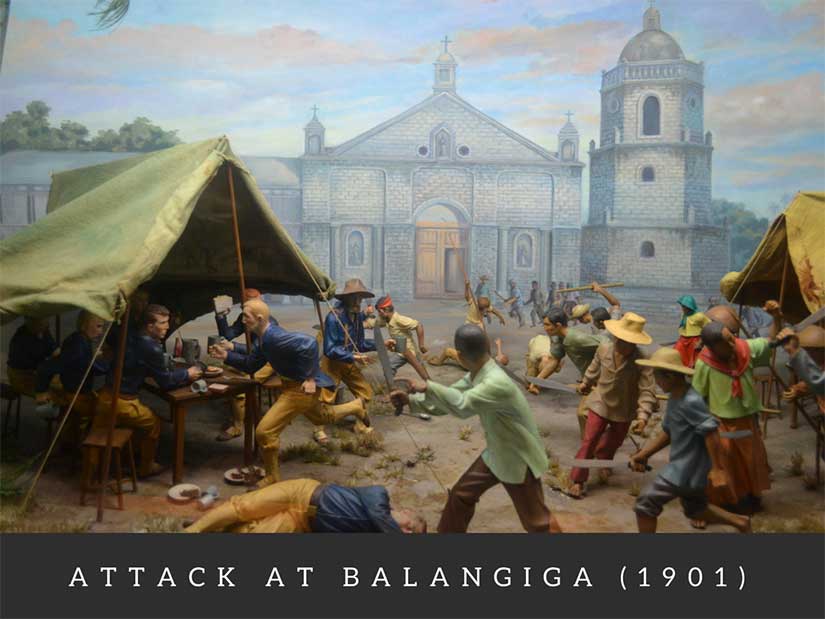

What happened at Balangiga

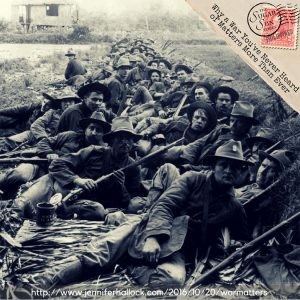

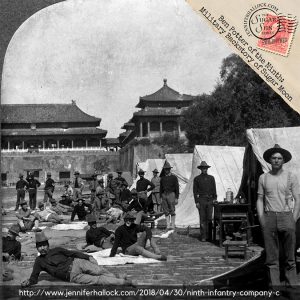

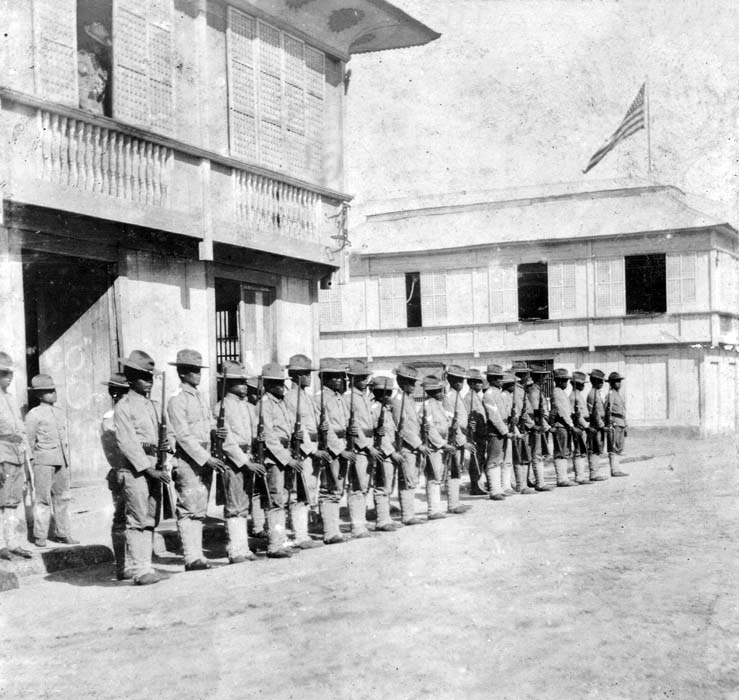

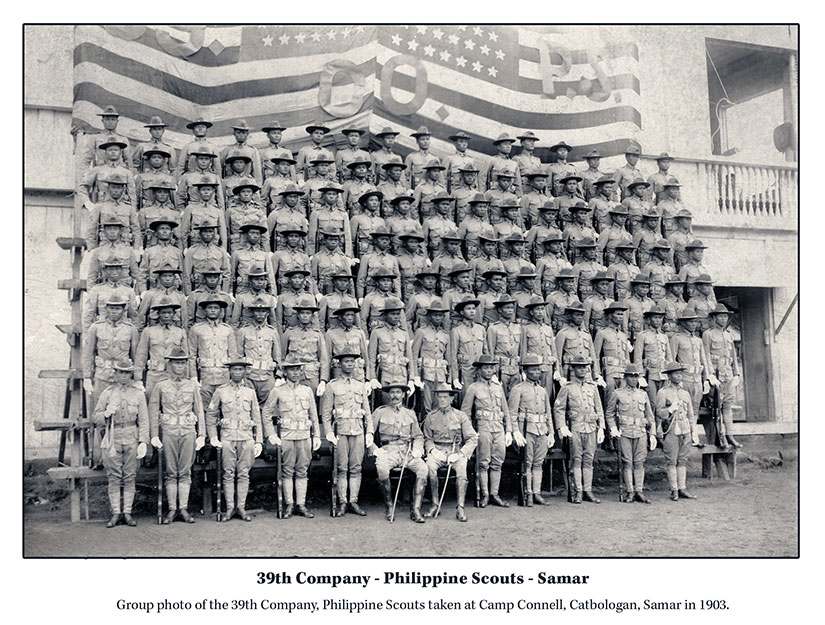

Charles King believed he was serving justice upon the people of Balangiga and southern Samar, punishing them for their uprising that killed 48 of 77 soldiers in Company C, Ninth Infantry. The story that King and everyone else was told was simple: the attack was unprovoked treachery on the part of ungrateful Filipinos led by General Vincente Lukban of the Philippine Revolutionary Army. It was not until Bob Couttie and Professor Rolando O. Borrinaga dug deeper that the truth was revealed.

Lukban’s lieutenants may have approved of the idea of the attack, but the real masterminds were the leaders of the town itself. They had just been pushed too far. Captain Connell, commanding officer of Company C, had upset the people with heavy-handed tactics, forced labor, and nightly imprisonment of the men in inhumane conditions.

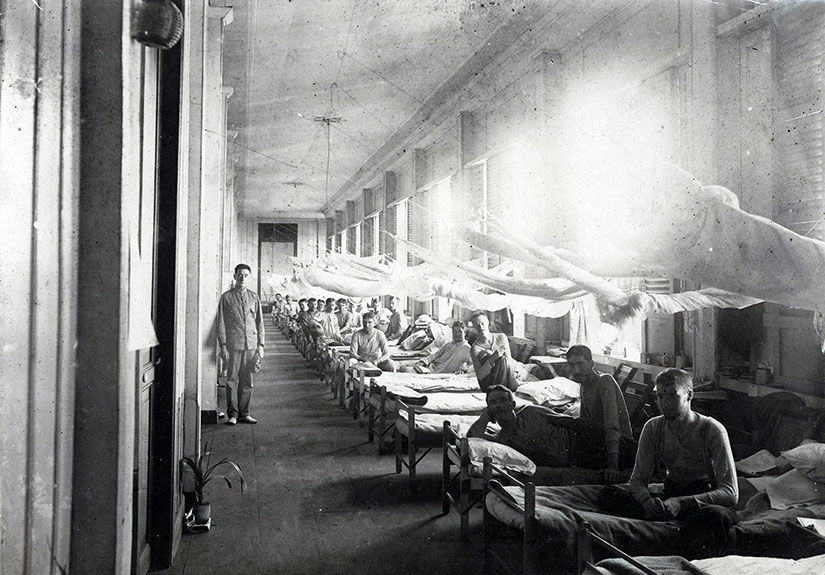

The town struck back. They sent the women away and drew in extra men from the surrounding villages. On Saturday, September 28, 1901, while many in the garrison were nursing hangovers from the previous night’s festival, the town attacked them at breakfast. It was a gruesome scene. The battle lasted a few hours until a handful of American survivors fled the town, eventually making it to a neighboring garrison—barely.

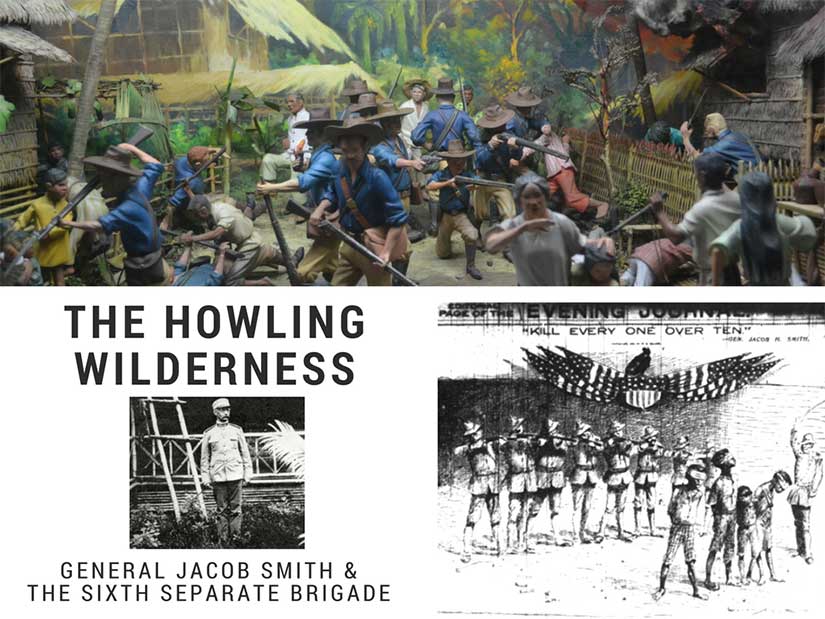

The Howling Wilderness

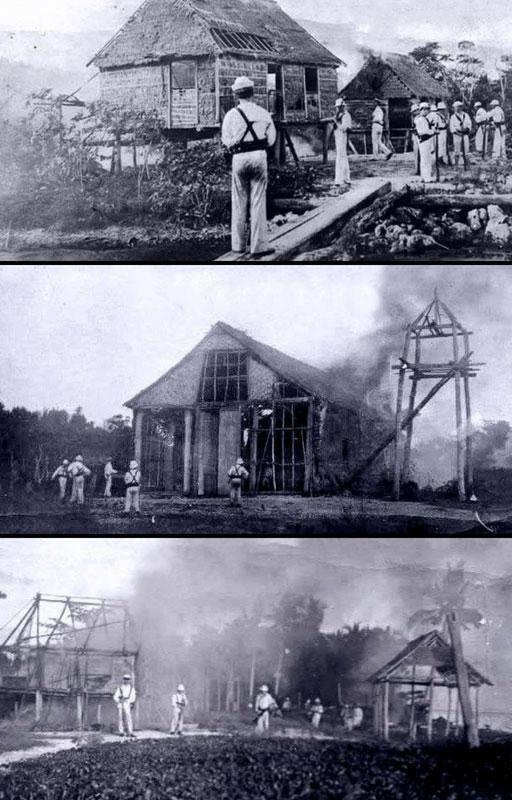

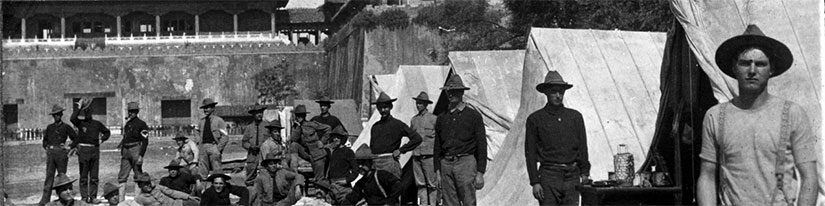

The very next day, an American expedition set out to burn Balangiga to the ground and, later, much of the rest of southern Samar. Their commanding officer, General Jacob H. Smith of the Sixth Separate Brigade, told them: “I want no prisoners. I wish you to kill and burn, the more you kill and burn the better it will please me.” He wanted his men to make Samar a “howling wilderness.” It was a disproportionate response that caused extensive and unnecessary suffering throughout the island.

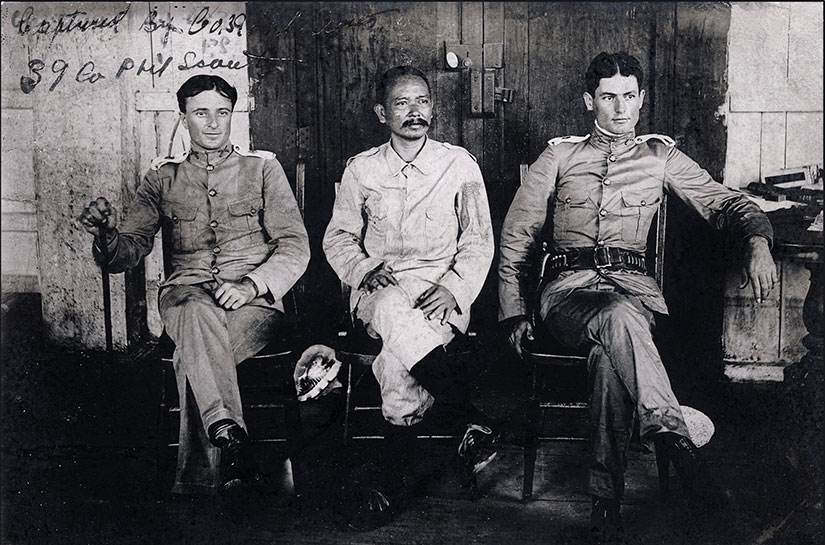

The Sixth Separate Brigade also went out looking for the priest of Balangiga, whom they believed had taken part in the planning and execution of the attack. It seems that Charles King was part of the team who found him.

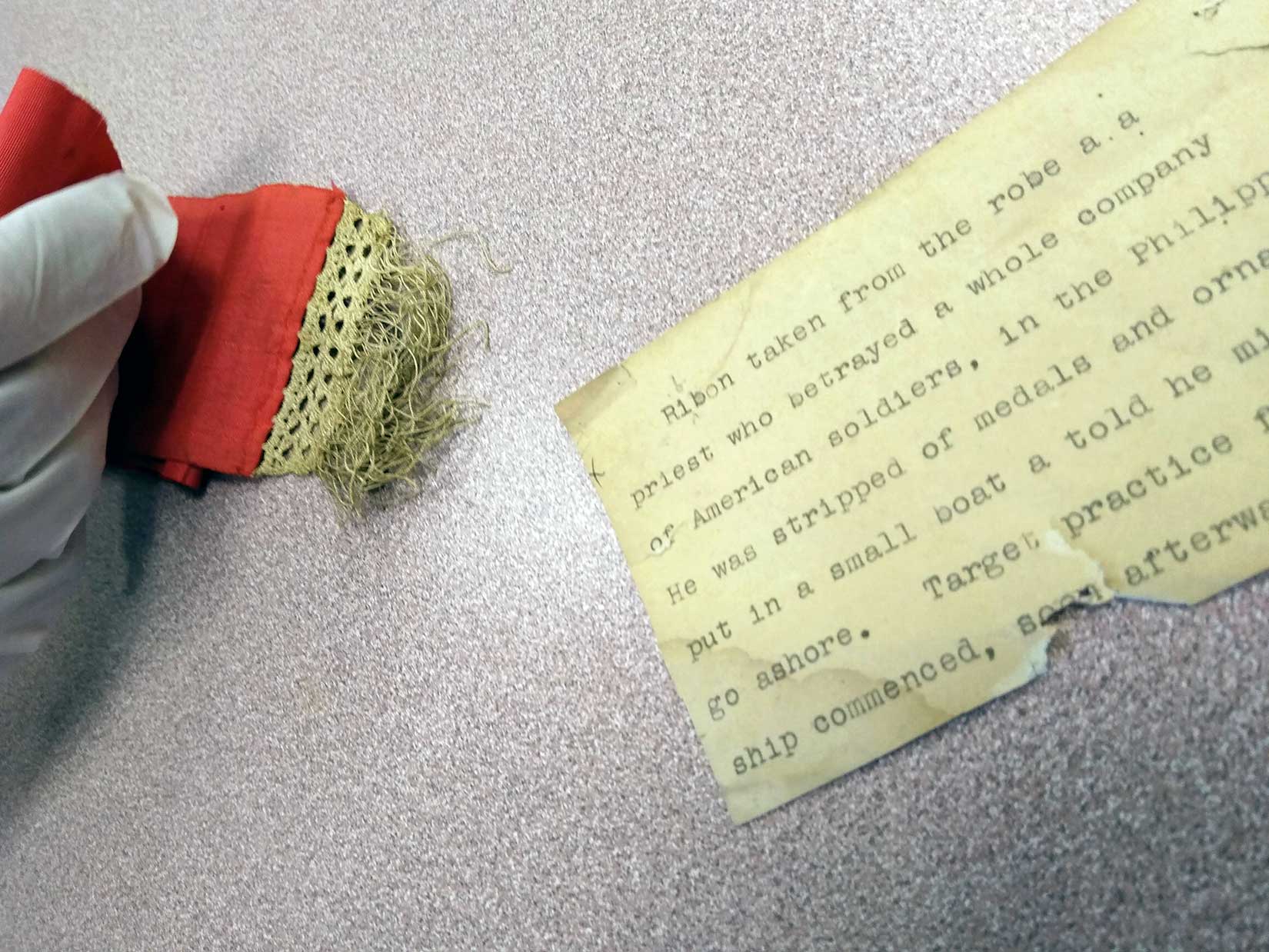

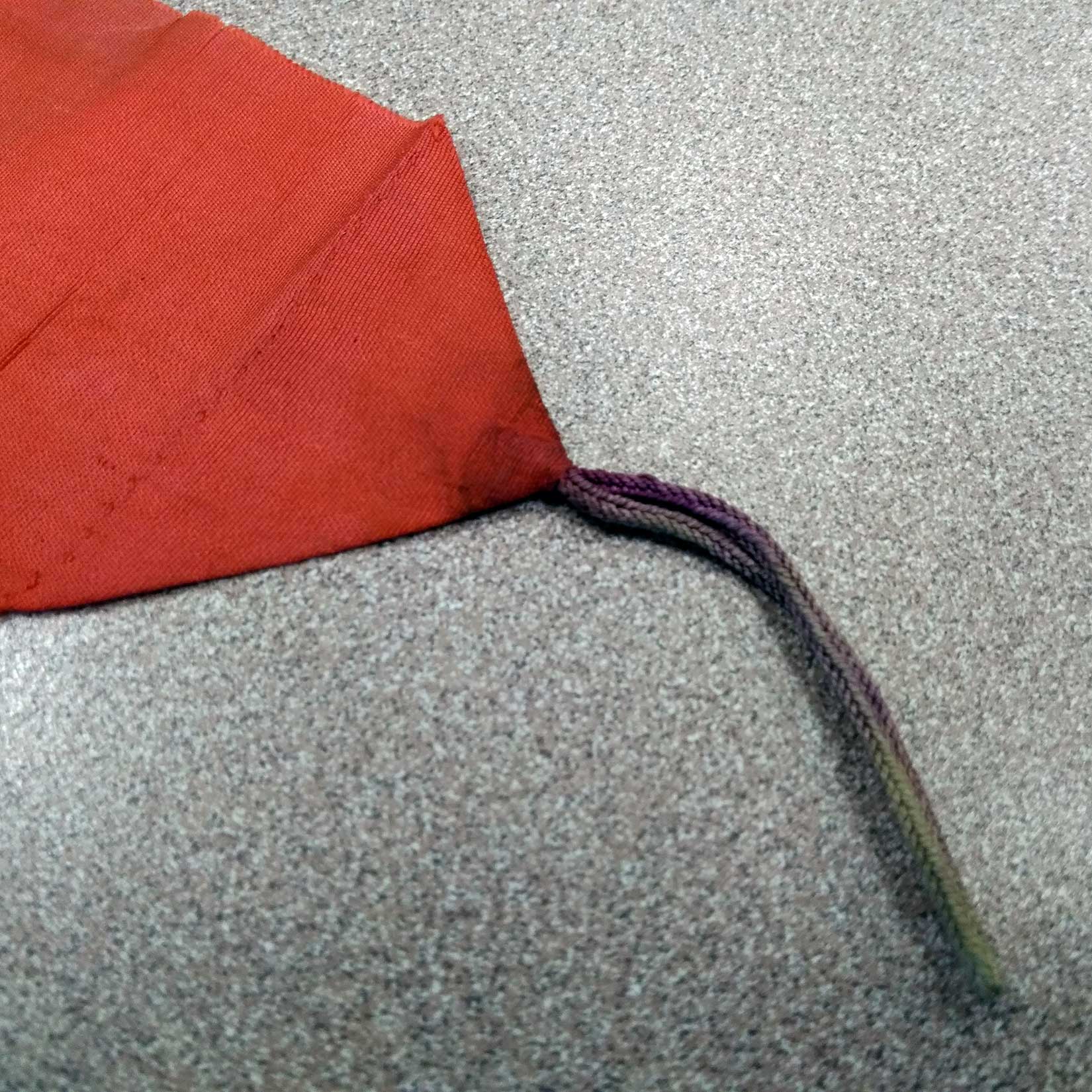

Guimbaolibot’s stole

The most important artifact left to the Derry students was the “ribon [sic] taken from the robe” of a priest who “betrayed a whole company of American soldiers.” The students would later find out that the priest, Father Donato Guimbaolibot, did not betray the Americans. In fact, Padre Guimbaolibot left town in order to remove his sanction from the events that would take place. He did not warn the Americans, true, but since the Americans were imprisoning all of the town’s men, about 150 people, in two tents built for sixteen, maybe the priest just wanted to get the heck out of there and find help.

Father Christopher Gaffrey, the Franciscan associate pastor at St. Thomas Aquinas, helped the students examine the ribbon—a stole, he informed them, which meant it was a sacred priestly vestment. When he looked at the loop, he noticed the original dye was likely a dark purple, the kind used for the sacrament of confession.

The students wanted to know more, and they got in touch with author and historian Bob Couttie, author of Hang the Dogs: The True Tragic Story of the Balangiga Massacre. Bob’s book was one of the key sources that I used for Sugar Moon. Bob helped them understand what had really happened—especially to the maligned priest who later was captured, tortured, and traumatized. Charles King likely played a part in Guimbaolibot’s ordeal because it was he who brought the sash home as a war souvenir.

Bob asked the students what they planned to do with the stole. The students answered as one: “Send it back where it belongs.” Matching the recent return of the bells, a public gesture, this is an amazing private gesture. Young they may be, but these students knew the right thing to do, without adult guidance. Their teachers support them, but they did not suggest this course.

Small World syndrome

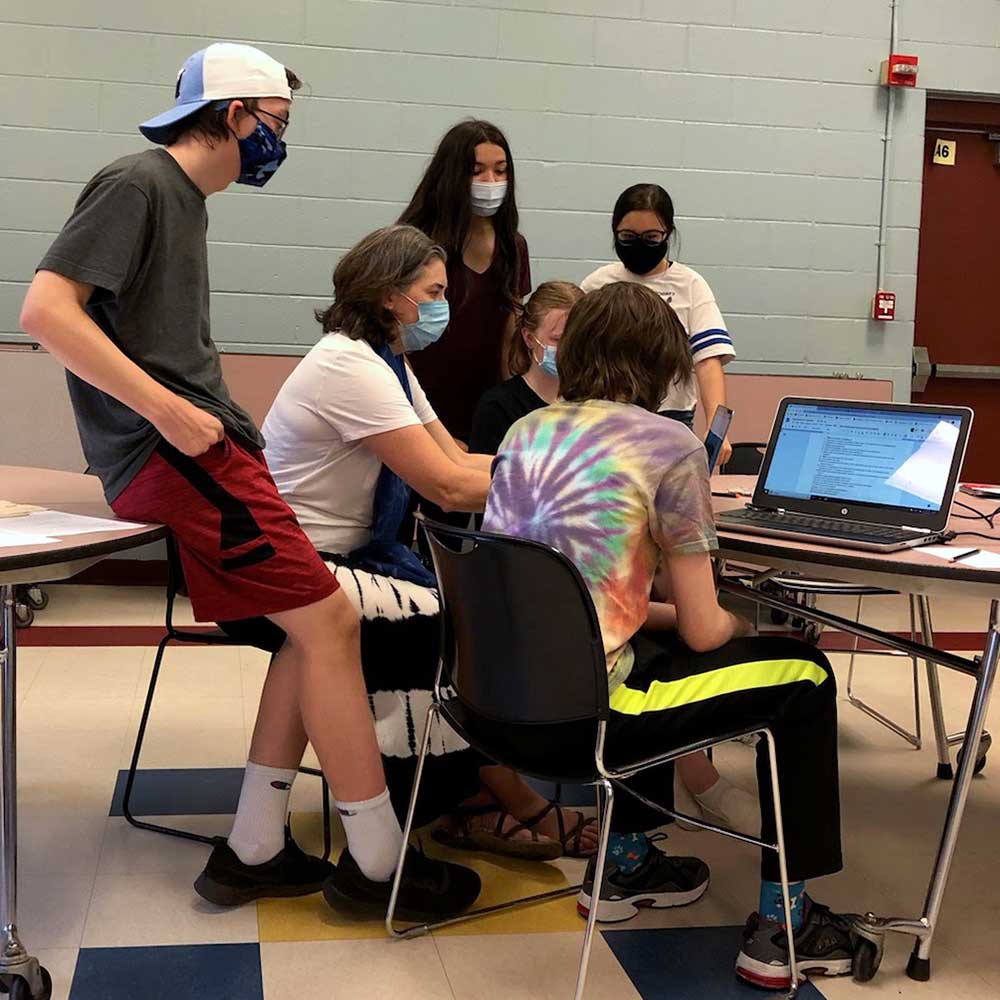

I knew none of what was happening just forty minutes down the road from my home. When I read the article, I could not believe what I had missed. But this week I was able to meet the students myself, see the artifacts, and answer more of their questions. I even told them the bus trip story. They do not need me, but I was at least able to help them identify a few towns and tell them a bit more about the wider context of this battle and what happened afterward. They asked wonderful questions about religious conflicts in the islands, about the diseases that worsened the civilian toll of the war, as well as current US-Philippine relations. Their curiosity was a credit to them, as if the whole enterprise has not already been.