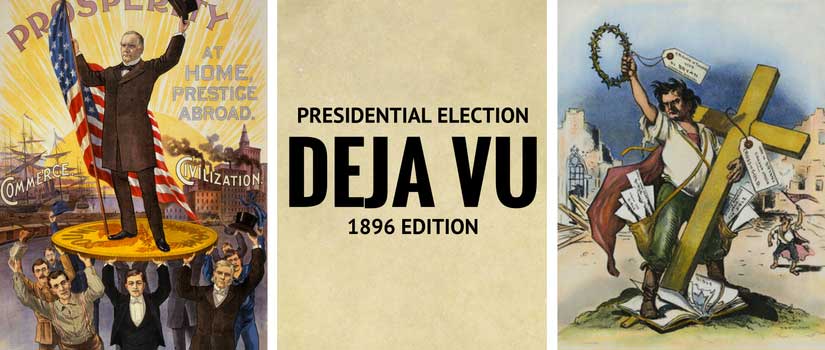

It’s like déjà vu—from 120 years ago. In this last week before the 2016 election, let’s take a look back to 1896. This way, as you listen to sound bites about jobs, banks, industrialism, and trade in the next few days, you’ll know that we’ve been here before.

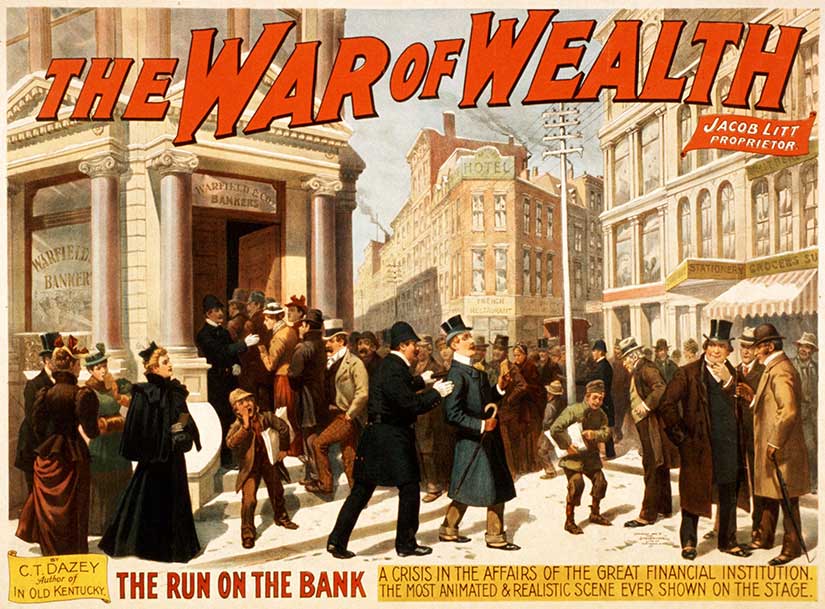

Back then we did not call economic downturns “recessions” or “depressions”; we called them “panics,” which has a refreshing honesty to it. The Panic of 1893 was a “war of wealth,” a pivotal event in a period known as the Gilded Age, a term coined by Mark Twain. Like today, the late nineteenth century was a time of growing divide between rich and poor—contrast the tenements of South Boston to the “cottages” of Newport. It was a global trend. Some economists have pointed out that we are in a new Gilded Age now, as modern wealth disparity approaches nineteenth-century levels.

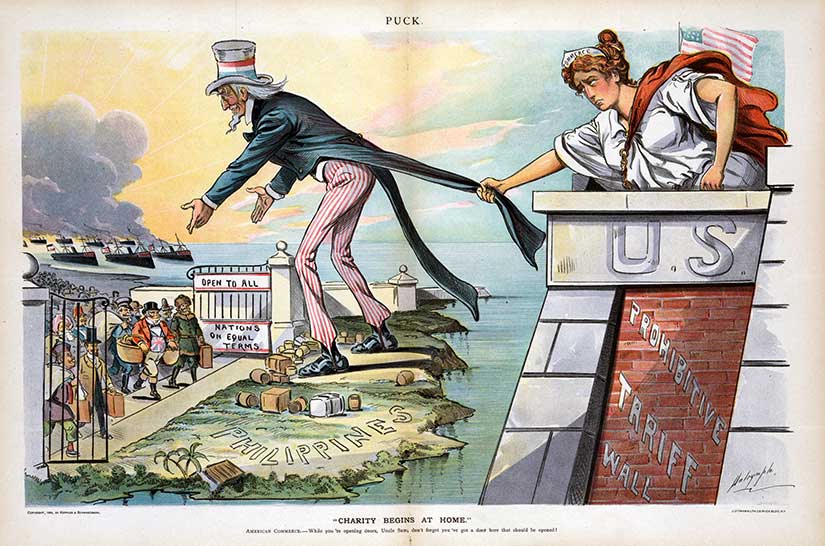

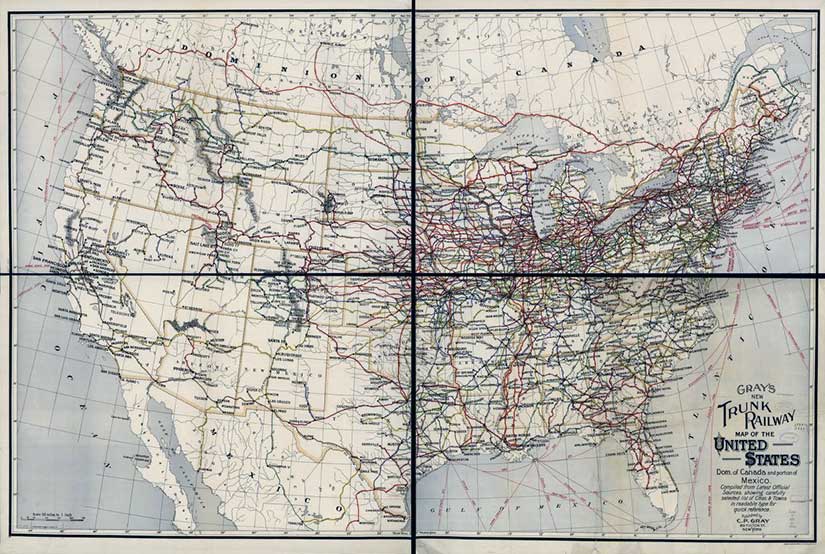

And like now, the Panic of 1893 was tied up in the new interconnectedness of the American economy—only they were talking about railroads and the telegraph, not Uber and the Internet. But, as is the case today, people were not sure what this would mean for the “old economy.” In the 1890s agriculture suffered, much like industry has in the last thirty years.

![A comparison of 1893 and 1983 structural change, with farms dying to pave the way for industrialism in 1890s [The Worthington Advance], and then those same factories dying in the 1980s [Ben Wojdyla].](http://www.jenniferhallock.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/10/825x619xStructural-Change.jpg.pagespeed.ic.E1HHlJYTYQ.jpg)

Banks, if they were lucky enough to survive the 1893 Panic, foreclosed on farms in the South, Midwest, and West. Our recent mortgage-crisis-fueled recession was countered by the Federal Reserve lowering interest rates to essentially zero, which they did by flooding our system with money. “Expansionary monetary policy” is pretty standard fare in economic textbooks these days, but this theory did not exist in 1893. And, by the way, neither did the Federal Reserve. But that did not make money supply any less of an issue. In fact, it made it more of one. Coinage was the election issue of the day in 1896 and 1900. You voted for a president based upon what you wanted to happen to the money supply. It was such an important topic of conversation that it even found a place in children’s literature.

![1900 poster advertising L. Frank Baum's Wonderful Wizard of Oz, courtesy of [Wikimedia Commons].](http://www.jenniferhallock.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/10/590x399xWonderful_Wizard_of_Oz.jpg.pagespeed.ic.0O81WNhr8y.jpg)

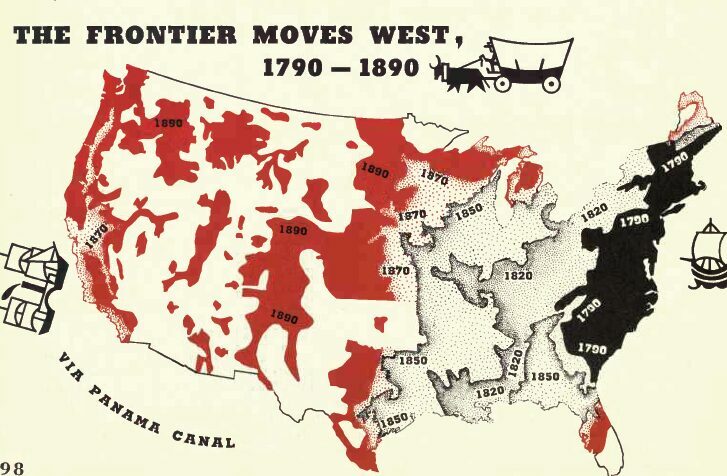

“Follow the yellow brick road!” In the original text version of The Wonderful Wizard of Oz, Dorothy’s slippers are silver. Silver eases Dorothy’s way along the “road of yellow bricks,” a metaphor for the gold standard. In other words, author L. Frank Baum showed that both precious metals, silver and gold, should be used for coinage in the United States, not just gold. This would expand the money supply, lower interest rates, and cause inflation—all policies that would help indebted farmers who were being crucified on a “cross of gold,” in the words of William Jennings Bryan, the Democratic candidate for president in both elections. Eastern industry opposed bimetallism because both owners and low-wage laborers stood to lose from inflation. This conflict—the rural heartland versus the East Coast elite—is a refrain you’ve heard before. In fact, the electoral maps of 1896 and 1900 predict the red-state-blue-state divide of today. In between then and now, the electoral maps bounced all around between Democrats and Republicans, but we have come full circle to the same structural change of the early 1900s.

![At bottom, a comparison of electoral maps from 1896 [Wikimedia Commons] and 2000-2012 [Wikipedia]. At top, the campaign trail of William Jennings Bryan [The First Battle].](http://www.jenniferhallock.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/10/825x618xElectoral-Maps.jpg.pagespeed.ic.pjmmdj5ih1.jpg)

Maybe the most important innovation Bryan brought to his candidacy, though, was his campaign itself. Bryan emerged out of the ashes of a Democratic Party he torched himself with populist and inflammatory rhetoric. He carried his message in person on a campaign tour through the Middle Atlantic and Midwestern states that lasted until two days before the election. Behaving in a way that most politicians and establishment figures considered “undignified,” Bryan went to the voters instead of waiting for them to come to his front porch—literally—and wait for a chance glimpse of him, which was Republican William McKinley’s strategy. (Some would say it was also Hillary Clinton’s strategy, given her comparatively restrained public speaking schedule in recent months).

![On left, Bryan speaks to a crowd in Wellsville, Ohio, courtesy of his own memoir [The First Battle]. On right, McKinley on his front porch only 50 miles away in Canton, Ohio [Remarkable Ohio].](http://www.jenniferhallock.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/10/825x308xMcKinley-Bryan.jpg.pagespeed.ic.2Yxurcdd9A.jpg)

By Bryan’s own account, he traveled nearly 18,000 miles and made nearly 600 speeches—about 20-30 a day, with Sundays off—and spoke to around 5,000,000 Americans, more than a third of the number who would cast a vote come November. Bryan wrote:

Friday was one of the long days. In order that the reader may know how much work can be crowded into one campaign day, I will mention the places at which speeches were made between breakfast and bedtime: Muskegon, Holland, Fennville, Bangor, Hartford, Watervliet, Benton Harbor, Niles, Dowagiac, Decatur, Lawrence, Kalamazoo, Battle Creek, Marshall, Albion, Jackson (two speeches), Leslie, Mason, and Lansing (six speeches); total for the day, 25. It was near midnight when the last one was finished.

Partly because of the silverite policy, which not all Democrats had supported, and partly because of this populist campaign style, a rival National Democratic Party (Gold Democrats) was founded, with its own nominating convention in Indianapolis. They put forward a former Union general and a former Confederate general on their ticket, but by the end of the campaign these men actually began to turn votes toward their Republican rival. At his last stop in Warrensbury, Missouri, presidential nominee John Palmer said: “I promise you, my fellow Democrats, I will not consider it any very great fault if you decide next Tuesday to cast your ballot for William McKinley.” (To some, this might feel like a certain third-party ticket of two former Republican governors—also from opposite sides of the country—who recently said that among the two-party candidates, they hoped people did not vote for Trump. Some saw this as a pseudo-endowment of Hillary Clinton, though the Libertarian Party quickly denied it.)

![An 1896 Judge cartoon shows William Jennings Bryan and his Populism as a snake swallowing up the mule representing his own Democratic party. Courtesy of [Wikimedia Commons].](http://www.jenniferhallock.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/10/825x585xBryan-devours-Democratic-Party.jpg.pagespeed.ic.uoNDJOOvIP.jpg)

There is more that ties 1986 to 2016, including the similarities seen between William Jennings Bryan and Donald Trump. Bryan spoke in a rhetorical style that elitist politicians snubbed but some people loved. In March, Daniel Klinghard wrote:

…like Bryan, [Trump] does have a long history of drawing audiences in the private sphere, an ear for the common tongue and an ability to paint complex problems in blindingly simple terms. Like Bryan, Trump is happy to play to paranoid impulses and vague conspiracies….Like Trump, Bryan appealed to what he deemed to be common sense and warned his listeners that anyone preaching moderation only intended to keep the common man in the dark.

Buckle up, folks. It’s going to be a wild few days.

Featured images: Republican William McKinley (left, from his own campaign poster) and Democrat William Jennings Bryan (right, in a critical Judge magazine cover). Both images found at Wikimedia Commons.