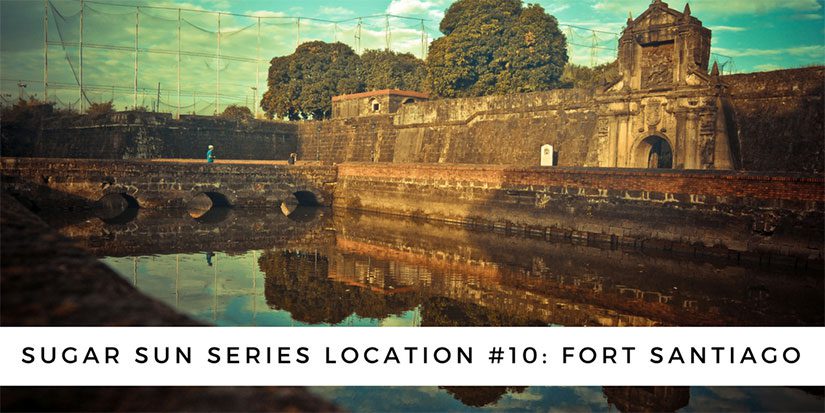

Georgina looked up at Fort Santiago, the stone embodiment of Spanish paranoia that capped the fortress city of old Manila. A bas-relief of Saint James the Moor-Slayer stood guard over the gate. Not the most observant Catholic, Georgie liked the thought of Iberian explorers braving the long, lonely journey across the Pacific only to find themselves back where they started: fighting Muslims. Judging by the number of churches they left behind, conversion had been a spiritual test they had met with gusto.

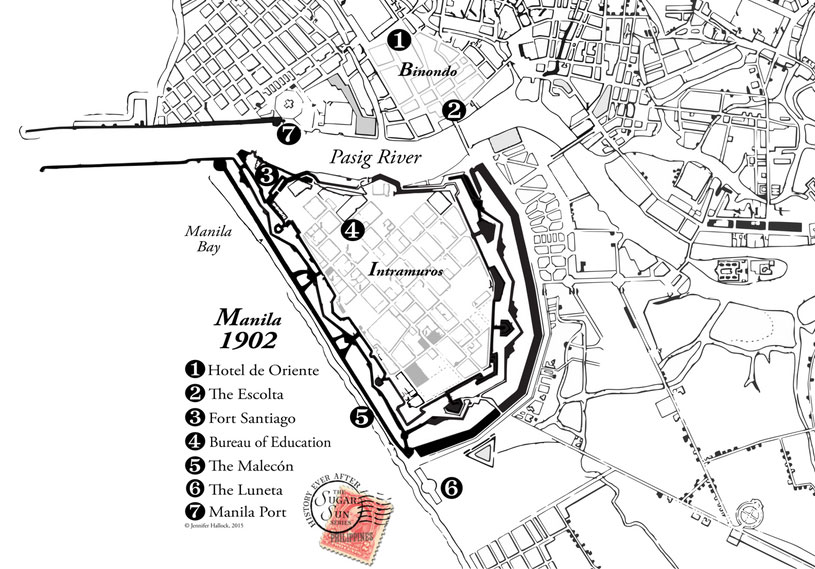

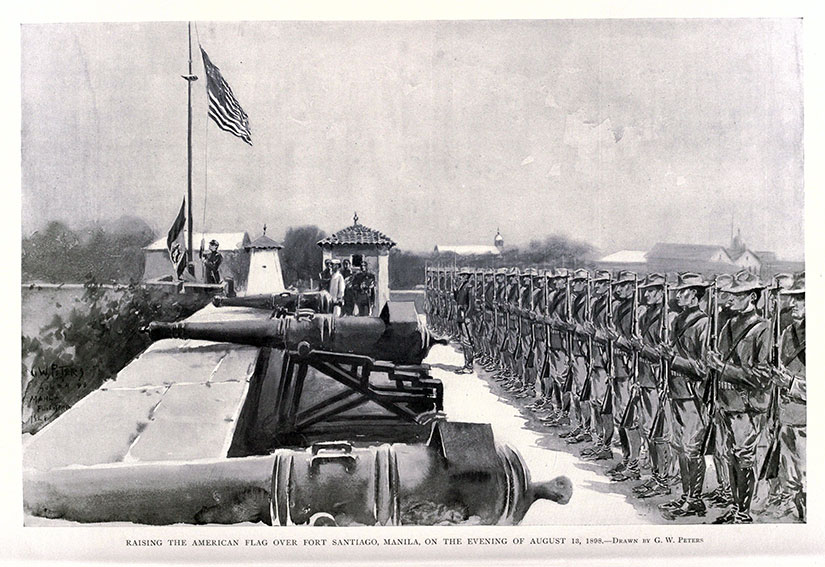

The defensive embankment of Fort Santiago (“Saint James”) has been around since shortly after the Spanish took Manila from its indigenous Muslim rajahs in 1571—hence, the tone-deaf dedication to Saint James the Moorslayer. (The Spanish converted or chased out most Muslims in the archipelago, but not all. Still today, 5% of Filipinos are Muslim, mostly in southern Mindanao and the surrounding islands.)

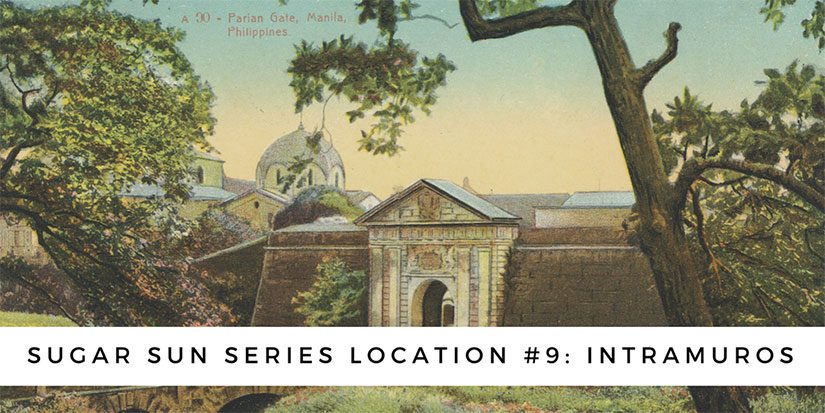

When a Dutch traveler painted Manila in 1665, you can already see the walled city of Intramuros, capped by Fort Santiago at the mouth of the Pasig River. This was where the Spanish Army was headquartered, and it will be the Americans’ choice, too. Almost 240 years later, my heroine Georgina Potter had no choice but to search for her missing soldier brother at Fort Santiago. (The relatively brief US stewardship may be the only time this citadel was not a fortress of Catholicism.)

Through the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, Manila grew into a thriving commercial and cosmopolitan center.

Every vessel that entered the city—from local casco to Manila galleon—had to sail past the intimidating cannons of Fort Santiago to reach the docks on the north side of the river.

Every vessel that entered the city—from local casco to Manila galleon—had to sail past the intimidating cannons of Fort Santiago to reach the docks on the north side of the river.

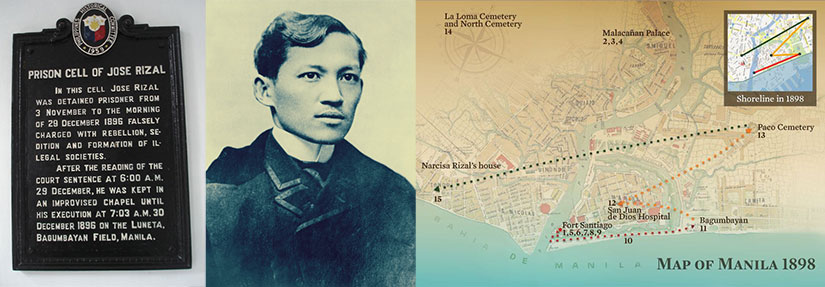

Importantly for Filipino history, Fort Santiago is also where national hero José Rizal spent his last days. In his spare time, this polyglot ophthalmologist authored the seminal work of Philippine fiction, Noli Me Tangere (Touch Me Not). The Noli blasts the corruption of the Spanish friars who ruled the countryside and reveals how young, intelligent Filipinos (like Rizal) were denied human and political rights. Since Rizal was executed for writing a work of fiction, the Spanish ironically proved his claims true.

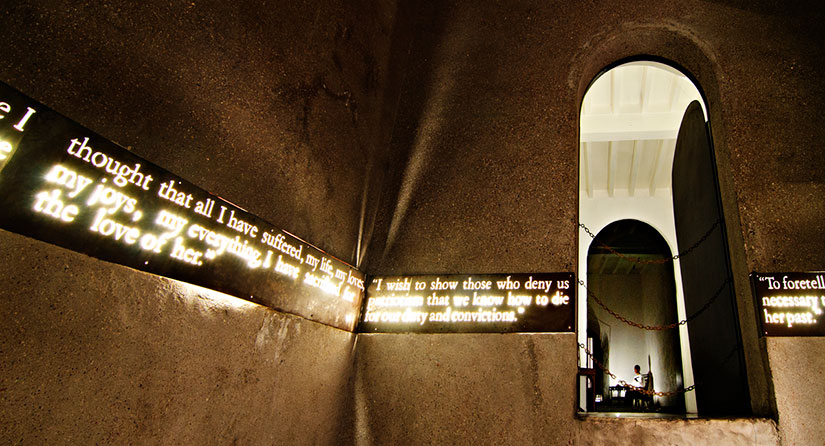

Rizal may have had revolutionary sentiments—how revolutionary is hotly debated—but his fate was ultimately sealed by priests, not politicians. Of course, these friars thought they were the government of the Philippines, so a challenge to them was a challenge to Spanish rule. Where did the friars put him? In their fortress of Saint James, of course. Rizal wrote these last words in his jailhouse poem, later named Mi Ultimo Adios:

My idolized Country, for whom I most gravely pine,

Dear Philippines, to my last goodbye, oh, harken

There I leave all: my parents, loves of mine,

I’ll go where there are no slaves, tyrants or hangmen

Where faith does not kill and where God alone does reign.

Scratch a stone in Manila and you’ll dig up all kinds of interesting history, right? By the way, the Creative Commons image below is by Fechi Fajardo. If you’re wondering what that net is, it’s a practice driving range for the Intramuros golf course! Oh, what would Rizal think?