Sugar was such a greedy crop, drinking the lifeblood of the soil like the aswang demons that peasants feared.

With the popularity of the Twilight series—or, let’s get old school with Anne Rice’s Vampire Chronicles—I am surprised that more writers have not widened their paranormal worlds to include the folk traditions of the Philippines. Though legends vary, the Aswang Project website has come up with three common characteristics of aswangs in them all:

- The aswang’s diet consists mainly of human liver and blood;

- It has an unholy preference for unborn children; and

- It is also known to prey upon children and sick people.

Um, did you notice number two? Aswangs have been blamed for miscarriages and stillborn babies all over the islands. Scholars say that Spanish Catholics spread the aswang legends to vilify the female midwives and folk healers, called babaylans, especially those in the interior of the southern islands. As this website describes:

When they know of a pregnancy . . . they would land on the roof of the pregnant woman’s home, and, trying to remain undiscovered, dig a hole to get inside. Once close, they use their razor-sharp teeth and their tongue that can stretch out as a thin wire to drink the blood and eat the fetus through the mother’s belly button . . .

Even worse, there is a related creature called a manananggal, who is a beautiful woman by day, but at night she detaches the upper half of her torso, sprouts bat-like wings, and flies around with her guts hanging out, looking for victims.

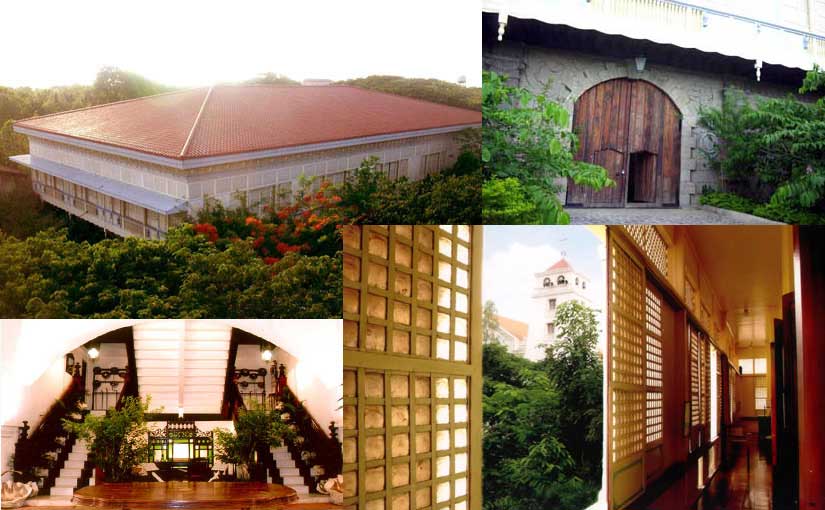

The aswang legends are particularly popular in the Western Visayas region, near where the Sugar Sun series is set. In fact, when Silliman University in Dumaguete opened their first dormitory in 1903, people thought it was haunted with these very creatures.

You may be wondering, how are aswangs created in the first place? What is their origin story? Getting bitten, like by a European-style vampire, is not going to do it. (You would just be dead, I think.) In the Filipino version, the dying aswang vomits up a small black chick—as illustrated below—which the aswang-to-be must swallow. Waiter, check please.

In European folktales, like those of the Brothers Grimm, the big bad wolf is eventually punished for eating children. But the victims of aswangs get no such justice. (Maybe because carrying a child to term and then actually delivering it has been the most dangerous thing a woman could do for most of history?) This is very dark stuff. I don’t write novels this dark, but someone should. I cannot imagine an aswang hero, but maybe that’s my lack of imagination.

Featured image from sweet00th on DeviantArt.