We’ve all been there. Or have we?

In the last twenty years or so, “Cringe humor,” with its “painful laughs,” has become a popular genre of television. Think The Office, especially the British version. We watch our favorite and least favorite characters embarrass themselves for our amusement. Wait—“amusement”? Some of these shows used real people and their real names. Time Magazine said of the Da Ali G Show: “The way Baron Cohen incorporated real people into his cringe-comedy was mean and unfair, but if it hadn’t been, it wouldn’t have been so revealing—or so funny.” I imagine for those people captured on camera, though, it was not just social awkwardness they felt afterwards. It was humiliation.

Where’s the line? We all have our little embarrassing moments we would like to forget. Many of us were socially awkward at one time or another. Maybe even outcasts. Growing up is hard. But what happens when our greatest humiliation comes in young adulthood, the time of life when we are supposed to be getting our act together? How do we go on? How do we find love? This is the reason why I was originally hesitant to read what you might call “cringe romance”: romance where one or both main characters must overcome a very public shame. But these stories need to be told. I am going to review one. And I ended up writing one, too.

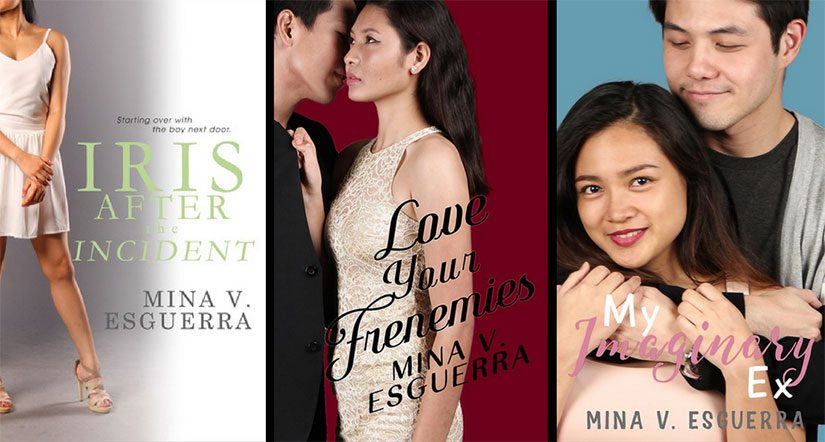

Mina V. Esguerra’s Iris After the Incident

Writing about humiliation and redemption is hard. It is a rare subject in romance because even if readers want their heroines to be “identifiable,” who wants to feel the humiliation of the main character so acutely? (Unless it is “humiliation kink,” which, yes, is a thing, and no one writes it better than Tamsen Parker in True North.)

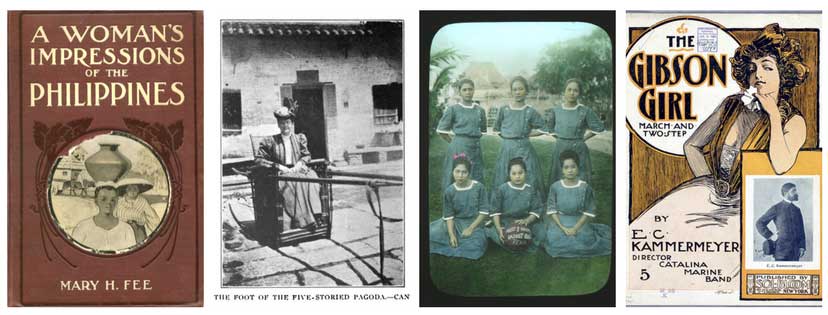

I finally picked up the latest in the Chic Manila series after listening to Mina V. Esguerra talk about it on the Book Thingo’s podcast. Esguerra is the leader and pioneer of the #romanceclass group of Filipino writers who innovate and entertain at the same time. I have read others in her Chic Manila series and have loved them. Because kilig (feels). I love that Esguerra is not afraid to make heroines out of her previous antagonists—like Kimmy Domingo, the anti-heroine of Love Your Frenemies. And, yay, Kimmy is in this book, too!

But Iris is not just rough around the edges, like Kimmy. She is not a difficult person. She is quite nice, actually. She has a good job helping young women get scholarships for math and science degrees. She works hard and seeks little credit for it.

But she is broken all the same. She has been utterly humiliated on a worldwide scale. Worst of all, the family who shuns her for shaming them were complicit in making her shame public. It is a real Charlie Foxtrot, as the book blurb says:

Whether she likes it or not, Iris’s life has been divided into two: Before the Incident, and After the Incident. Something very private was made very public, and since then life has been about recovering from being shamed, discovering her true friends, and struggling to find a new normal.

The “something very private” is revealed less than ten percent into the story, but if you do not want to know what it is, stop reading here.

No, really. If you don’t want to know, you need to stop reading now.

Okay. You want to know. Yes, it’s a sex tape. But that sounds more sordid than it really was. Let Iris tell it:

I had sex with my boyfriend.

And we took a video.

And it accidentally got out on the internet.

People saw it.

When Iris says “accidentally,” she really does mean it. It should not have happened. But it did.

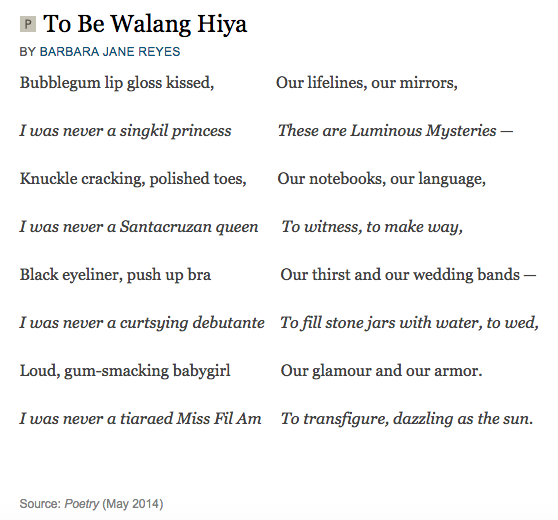

And in the beginning, it was still an anonymous sex tape. Life could go on—until a certain member of Iris’s family tried to “clear the air” and blew the lid right off the scandal. Iris’s humiliation is especially acute in the context of Philippine society. To be “walang hiya”—shameless or unconscionable— is one of the worst insults in the Tagalog language. Because Iris’s scandal becomes the whole family’s scandal, the family blames Iris for their collective misfortune.

The full scope of Iris’s mortification may be hard for non-Filipino readers to understand. In the New Zealand television show Outrageous Fortune, a young woman named Pascalle sets up and leaks her own sex tape in order to encourage notoriety. In the United States of Real Life, Kim Kardashian, Paris Hilton, and Rob Lowe made (or remade) careers out of this kind of “fame.” But for Iris Len-Larioca, the heroine of Esguerra’s novel, her sex tape is The End of Days. And she does what you might expect: she hides.

No, she really hides. She moves out of her family home into a small one-bedroom apartment, works a graveyard shift to avoid people in the office, and takes a demotion so she can cower behind a computer instead of wooing clients in person. For a while, she makes her own baking soda toothpaste to avoid the local convenience store.

Surprisingly, though, this broken woman still has a great sense of humor. She retells her own story as if she is writing a grant application—because her job is evaluating grant applications. Bitter sarcasm, self deprecation, and witty rejoinders abound. Iris’s voice is very Bridget-Jones-meets-Jessica-Jones. For example, in a particularly embarrassing scene on a cable car in Tagaytay, she shocks everyone with her honesty: “I’d opened the can of worms, anyway,” Iris thinks to herself. “Worms all over the place.”

Esguerra has made Iris real. And unique. While her voice can be funny, it is also determined, level, and self-aware:

Sometimes I wished that I could be that person that no one singled out, that no one used as an example or a cautionary tale.

Good luck.

We could only move forward.

And Iris tries to move forward. The real story is, in fact, a romance. She tries to move forward with a man just as broken as she is—and for similar reasons. Gio Mella’s sexual skeletons were plastered all over the internet, too. He is also hiding, but in a different way. While Iris wants to know everything said on the internet about her—she has even set up email alerts—Gio has no internet and no phone. The Philippines is the twelfth largest cell phone market in the world, so that essentially makes Gio a unicorn. The lack of phone provides both conflict and wonderful feels in the resolution of the book.

You should know, though, that this book is not plot heavy. No one is kidnapped. No commandos storm the compound. A little bit of scholarship and cosmetic business is conducted—great alternatives to the typical billionaire romance trope—but all of these minor adventures merely serve to put two recluses into closer and closer contact with the world. And we get to see how they fare.

And there is sex. Wonderful, hot sex.

As Sue of Hollywood News Source wrote on Goodreads: “Iris After the Incident is the most feminist & empowering romance book I’ve ever read.” This book is sex-positive. Because the sex on Iris’s tape was consensual, sex itself is not ruined for Iris—just trust. Iris will have to learn to trust Gio, but she knows that she wants to have sex with him—and how. She and Gio have chemistry. Literally:

What I liked about him being on top was I got to watch him. Watched the tension in his arms, his shoulders, the way his hips, his torso, his entire body worked for his pleasure and mine. It was hot, and one of the best ways to cap an hour-long discussion on chemistry, in my humble opinion.

Obviously, there is a future for this couple. If I called it “happy for now,” that would be accurate, but it would minimize the strength of the relationship. “Happy for now” is “happily ever after” for people like Iris and Gio. “Ever after” is too much to think about. Now is the victory. They have now, and I know they will keep having now for many, many nows in the future.

My only quibble with the ending was that Tita Ara did not get vanquished in some spectacularly vivid fashion. I am not usually a mean-spirited person, but there it is.

Iris After the Incident takes on a devastating challenge, but it wins our hearts. It is both a cautionary tale—for my students who put private information on the internet all the time—and an encouragement to persevere.

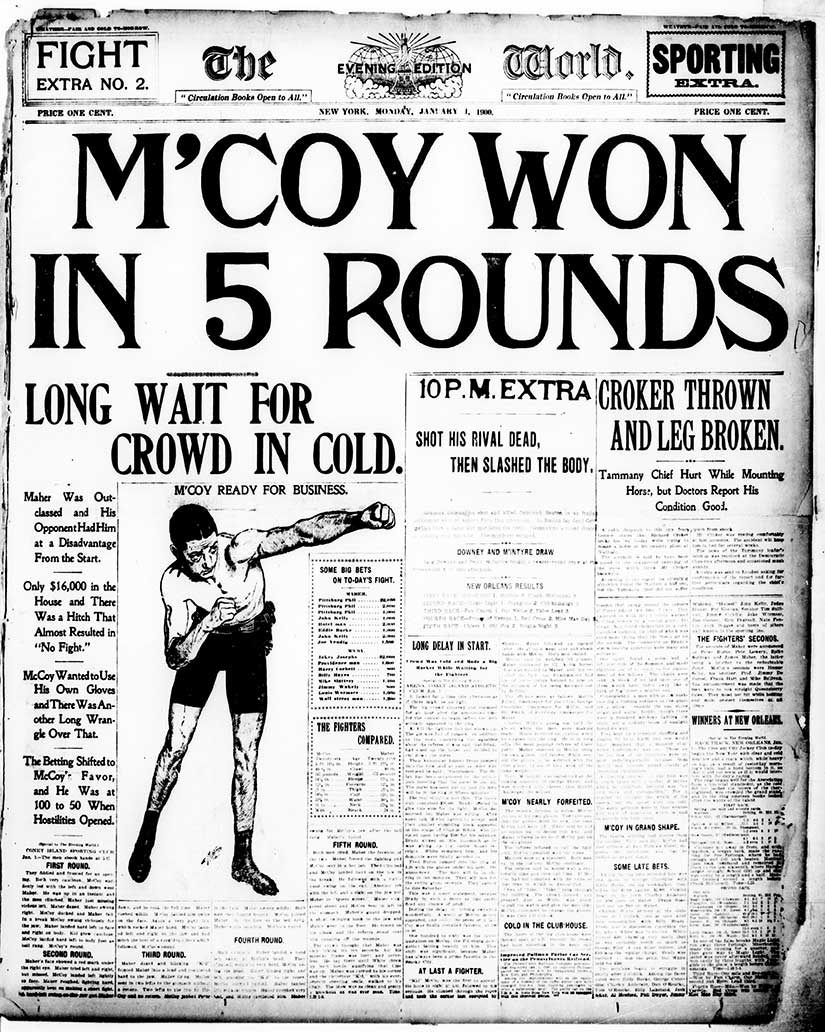

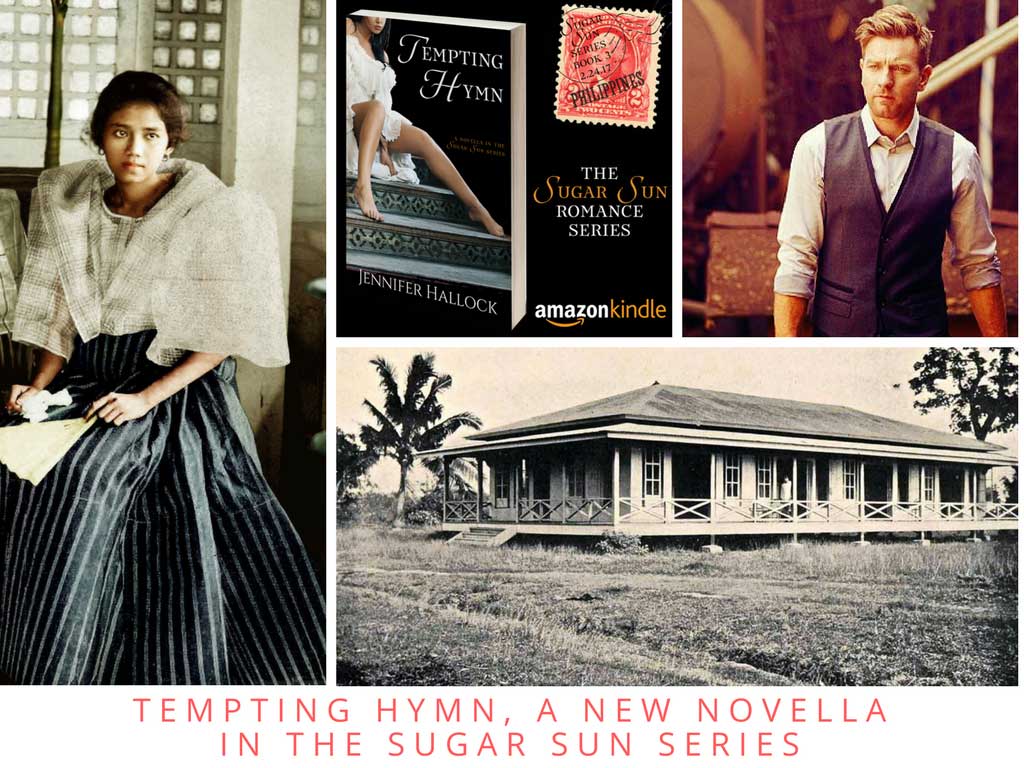

Tempting Hymn, novella 1.5 of the Sugar Sun series

The heroine in my upcoming book, Rosa Ramos, goes through struggles similar to Iris, but in a very Edwardian era sort of way. Her mistakes were not broadcast on the internet, of course, because it is 1904. But that also means Rosa cannot hide away in the anonymity of modern society. Everyone in Bais knows her story—and if you’ve read Under the Sugar Sun, then you do, too. Rosa was left not only with a soiled reputation, but also a child to support. Adding to her problems—and everyone’s problems, really—are the issues of class and race in the American colonial period.

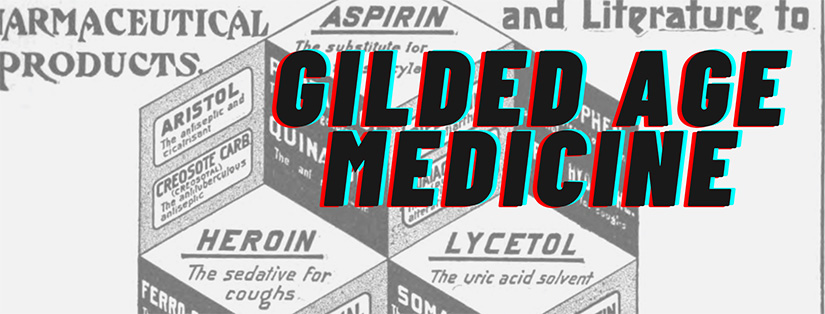

My hero, Jonas Vanderburg, is broken, too—but in a very different way than Gio, Iris, or Rosa. This Midwestern missionary’s entire family died in Manila during the cholera epidemic of 1902—an unexpected sacrifice that Jonas has no intention of surviving alone. But Rosa, his nurse, needs to heal him so that she can support her son and redeem her professional reputation. Neither of them want a marriage of convenience, but you can’t always get what you want.

I look forward to sharing this story with you next month. Stay tuned for news. And, until then, read Iris After the Incident, the whole Chic Manila series, and the rest of the #romanceclass collection. I will leave you with a poem:

Featured image is a trilogy of sorts: Iris After the Incident builds upon characters introduced in Love Your Frenemies, which in turn redeems a character you love to hate in My Imaginary Ex (pictured here in a three-book set).