Happy Fourth of July, Republic Day, Philippine-American Friendship Day, and 21st Hallock wedding anniversary! (Yes, Mr. H and I married on American Independence Day because we enjoy irony.)

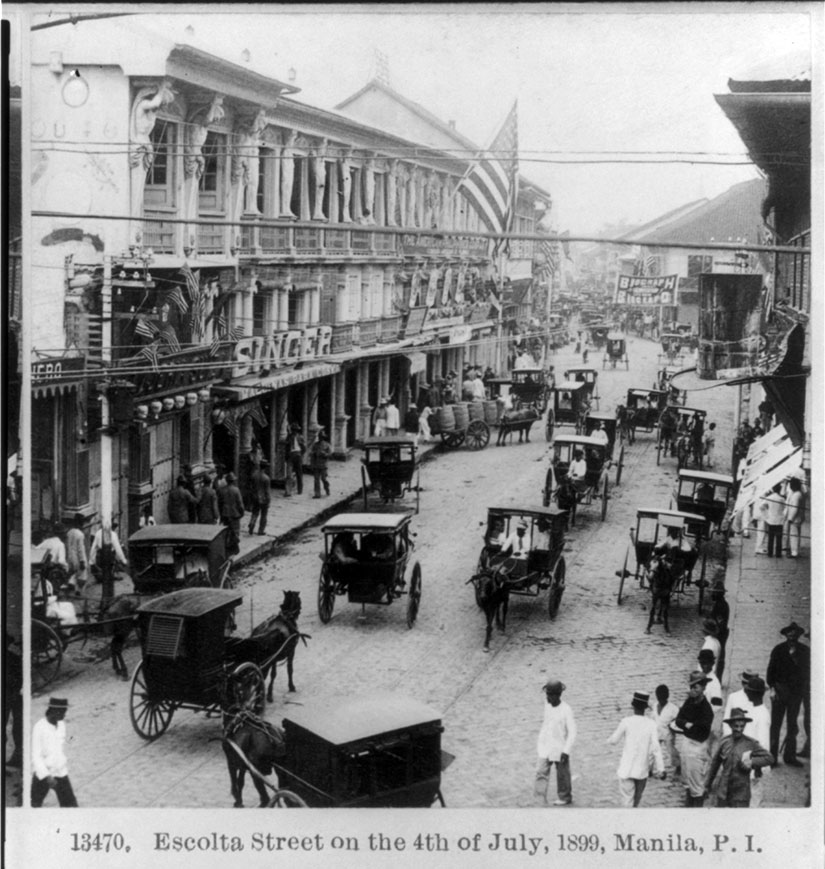

The American administration in the Philippines could be quite cheeky too: they liked using the Fourth of July as a marker date in their administration, despite the fact that seizing the islands turned the US into the very redcoats we declared unfit oppressors via the Declaration of Independence on July 4, 1774. (Independence was actually declared on the 2nd of July, but never mind.)

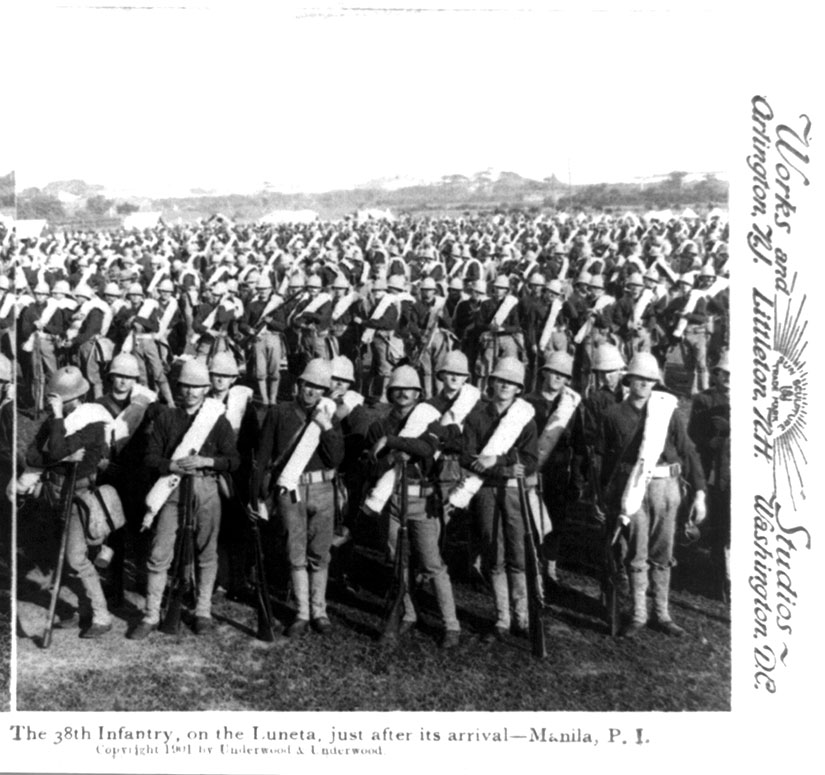

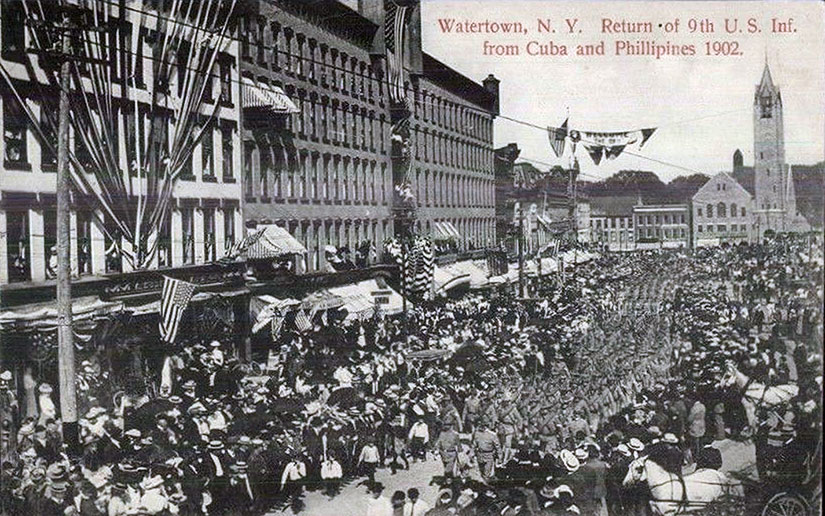

The Insular authorities used July 4, 1902, as a declared “mission accomplished” date, ending (supposedly) what was then called the Philippine Insurrection. Much like George W. Bush’s gaffe over a hundred years later, though, the mission was very far from accomplished. In fact, the Philippine-American War would not be over until 1913.

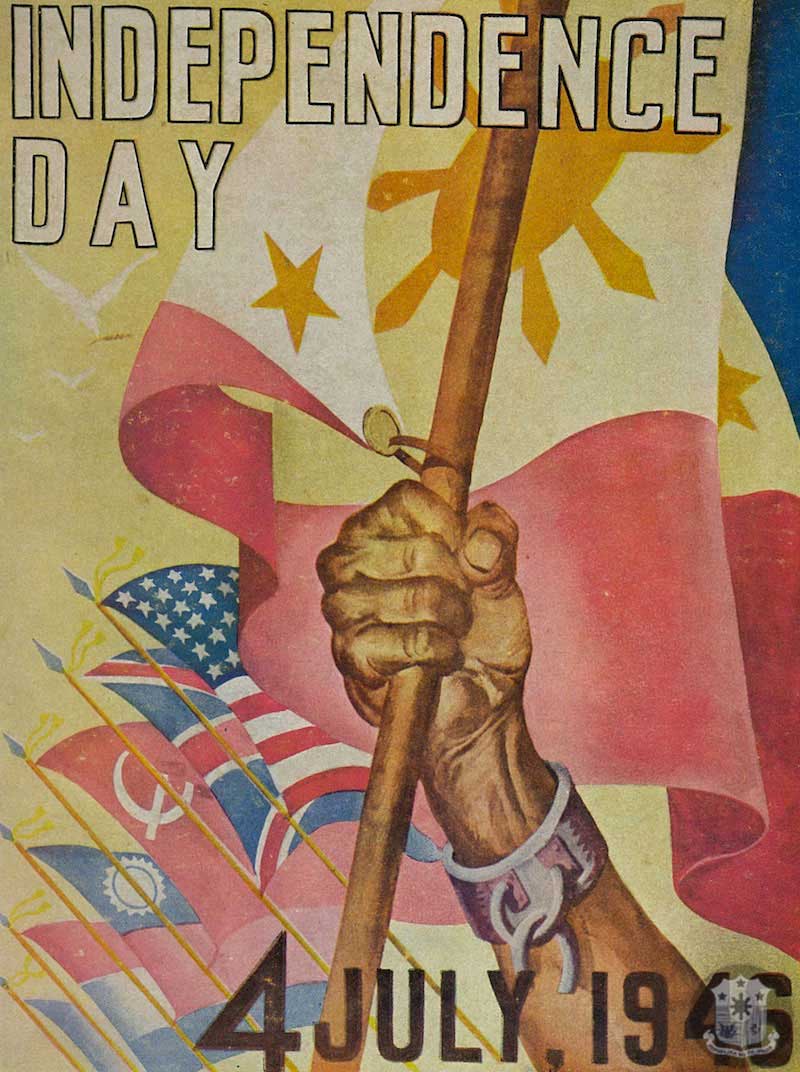

Cheekier still, when setting up the path to Philippine independence, the American authorities decided to terminate the Commonwealth on July 4, 1946—so that conveniently we and our former colony (but still beholden to the US under the Bell Trade Act of 1946 and Military Bases Agreement of 1947) would have the same independence day.

July 4th was celebrated as such until Philippine President Diosdado Macapagal changed the law in May 1962, recognizing June 12th as the true date of Philippine independence—honoring the day that President Emilio Aguinaldo established the First Philippine Republic in 1898. That was before the Americans even decided to keep the islands as spoils of the Spanish-American War. This makes sense, but it took them sixteen years to do it, which shows you how large the American footprint still was in early Cold War-era Philippines.

4 July 1946 was still relatively important, of course: it marked the birth of the Third Republic. (The Second Republic was under Japanese occupation, in case you were wondering.) Therefore, the Fourth of July was renamed Republic Day. But after President Ferdinand Marcos enacted martial law and then a new constitution in 1972, he decided to rename the day yet again to Philippine-American Friendship Day.

Commemoration post-Marcos has returned to Republic Day, but my friends and I still choose to celebrate Fil-Am Friendship Day (and the Hallock anniversary) with ice-cold San Miguel, guitars, and good food. To our friends and found-family in the Philippines, we miss you all and wish we were there to celebrate with you.

For more photographs and history behind this day, see the Official Gazette feature. The banner photograph at the very top of the post is Manuel Roxas and Douglas MacArthur shaking hands at Roxas’s inauguration, courtesy of the Philippine Photographs Digital Archive at the University of Michigan. (Whether this was Roxas’s inauguration as the third and last president of the American Commonwealth of the Philippines on May 26, 1946, or his inauguration as the first president of the Third Republic of the Philippines on July 4, 1946, I cannot say for sure—but based on the chairs, I think it is the latter.)

Happy day, everyone! Our marriage is now old enough to drink in the United States, so happy anniversary to Mr. H!