Praise for Sugar Moon, the second full novel in the Sugar Sun series:

Named one of the “10 Best Historical Romances with Sports“ by Frolic!

“So this book I was saving for the long weekend? Readers, I just finished it. WHY DID I READ IT SO FAST?…Pretty sure Allegra will be my favorite heroine this year.” (★★★★★ review by Kat of BookThingo on Twitter and Goodreads)

“Fantastic!…a comprehensive fictional characterization…” (Rolando O. Borrinaga, Ph.D., leading expert in the history of the Balangiga Incident)

“…this richly layered romance is filled with vivid details of a location not often found in historical romance…” (Bestselling author Joanna Shupe)

“I cared intensely for Allegra (Allie), a young woman who knows what she wants but not how to get it, and Ben, who doesn’t believe he deserves to have anything at all….Ben, a curmudgeon of an opium addict who I instantly disliked in Sugar Sun, is transformed through some sort of writerly witchcraft into a sympathetic character I couldn’t help but root for.” (★★★★★ review by Alexa Rowan on Goodreads)

“Highly recommended.” (Historical Novel Society review)

“These characters were so vibrant!…The portrayal of women—and Allegra in particular—uplifts and inspires…Sugar Moon sparkles with wit and romance…” (Michaelene M.’s review in Historical Romance Magazine)

“Smart, engaging, and unspeakably naughty.” (★★★★★ review on Amazon)

Ben and Allegra’s story was “on a completely different level.” (Joy Villar’s review on Twitter)

Read Sugar Moon for free on Amazon’s Kindle Unlimited.

Praise for Tempting Hymn, a novella in the Sugar Sun series:

Praise for Tempting Hymn, a novella in the Sugar Sun series:

A- and Desert Isle Keeper from All About Romance: “If you like underrepresented settings, social class conflict, intercultural romance, working class characters, or just damn good historicals, the Sugar Sun series is one to get into. I’m certainly developing a sweet tooth!”

“Reading this book feels like a spoon gliding through a custard dessert.” (Phebe on Goodreads)

“Tempting Hymn manages to give adequate breathing room to the harsh historical realities of American colonial rule in the Philippines, while delivering a romance that is sweet, realistic and – above all – emotional….Hallock doesn’t pull any punches in Tempting Hymn, with either the romance or the historical detail. She does her setting and her characters justice, delivering a story that is raw and unflinching, but never too dark, because it has an engaging and touching romance at its core. [And] all the sex scenes here are insanely hot, just like in Under a Sugar Sun.” (Dani St. Clair, Romancing the Social Sciences)

“This novella does a hell of a lot of work between the lines. It’s actually breathtaking.” (Kat at BookThingo, posted on Twitter)

“The pairing here is American man/Filipino woman and that is a tricky, sensitive trope…but it’s handled with deft and care. And dignity.” (Mina V. Esguerra, author of Iris After the Incident, reviewed on Facebook)

“…the first love scene between Jonas and Rosa is a master class.” (Bianca Mori, author of the Takedown trilogy, reviewed on Goodreads)

Read Tempting Hymn for free on Amazon’s Kindle Unlimited.

Praise for Under the Sugar Sun, the first novel in the Sugar Sun series:

Praise for Under the Sugar Sun, the first novel in the Sugar Sun series:

“If you’re looking for a meaty historical romance that will transport you somewhere you’ve never been, Jennifer Hallock’s books…are must-reads.” (Courtney Milan, NYT bestselling author of The Duchess War.)

“Intensely absorbing…the charged political climate of the day is drawn with refreshing nuance.” (Laura Fahey review for Historical Novel Society)

“Two pages in and I was utterly hooked. I sensed the voice of a confident writer and spied the shorelines of a diligently-researched world. I finished it this weekend, hungry for more.” (Bea Pantoja, blogger)

“It will take me a few days to recover from reading Jennifer Hallock’s beautifully written novel. It was vivid, funny, unflinching, poignant, and sexy…. I didn’t want to say goodbye to Georgie and Javier.” (Suzette de Borja, author of The Princess Finds Her Match, reviewed on Facebook)

“Oh my god this book!…And I’m usually not into the high-stakes romance because my heart doesn’t want to handle it, but this guy…” (Mina V. Esguerra, author of Kiss and Cry and the Chic Manila series).

“It’s a perfect read for those who love their romance with a little more plot, and for history buffs who want to see a different perspective on the Philippines.” (Carla de Guzman, Spot.ph on “10 Books That Will Take You Around the Philippines”)

“…Under the Sugar Sun was also just a great romance, the kind that makes you feel squiffy in the stomach when you remember it at odd moments during the day…grand in scope in the same way old-school romances were, but with a very modern presentation of race, class and gender.” (★★★★1/2 review by Dani St. Clair of Romancing the Social Sciences)

Read Under the Sugar Sun for free on Amazon’s Kindle Unlimited.

Praise for Hotel Oriente, the prequella novella to the Sugar Sun series:

“The strength of this book, aside from the lyricism with which it describes Manila in what was arguably its heyday, is the intimacy between Della and Moss.” (Five-star review from Kat at Book Thingo)

“. . . a quick but delightful read. I loved that the plot played on a real profiteering scandal that occurred at the Hotel de Oriente, but I was equally intrigued by Hallock’s heroine.” (Erin at Historical Fiction Reader)

“I loved this book. It’s got an easy, fluid style that’s both readable and vivid.” (Author Erin Satie)

“…a stellar novella…[with] political intrigue, a sexy hard-working hero, and fascinating details about early 20th century Philippines. Her stories are beautifully-written and painstakingly-researched.” (Penny Watson, author of A Taste of Heaven, reviewed on Goodreads)

Find Hotel Oriente at Amazon as a standalone novella, or grab it as part of the Romancing the Past anthology wherever you purchase your ebooks, starting September 15, 2021.

The Sugar Sun series an epic family saga of love and war at the beginning of the twentieth century. Books are listed below in reverse-publication order, starting with the latest releases first. This series does not need to be read in order, however, and all are interconnected-yet-standalone happily-ever-afters.

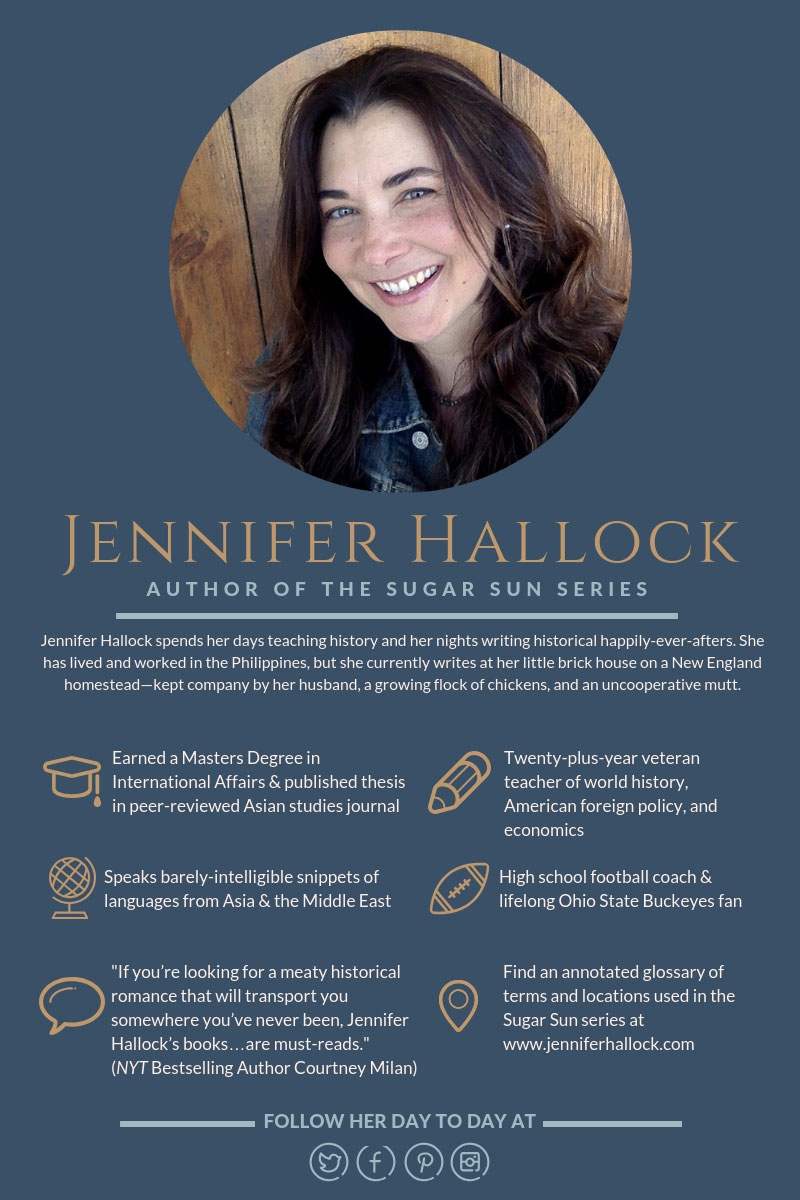

Author Bio:

Jennifer Hallock spends her days teaching history and her nights writing historical happily-ever-afters. She has lived and worked in the Philippines, but she currently writes at her little brick house on a New England homestead—kept company by her husband, a growing flock of chickens, and a mutt named Wile E.

Author Details:

Jennifer is available for speaking engagements, interviews, and appearances. She is also happy to speak to reading and writing groups via Zoom.

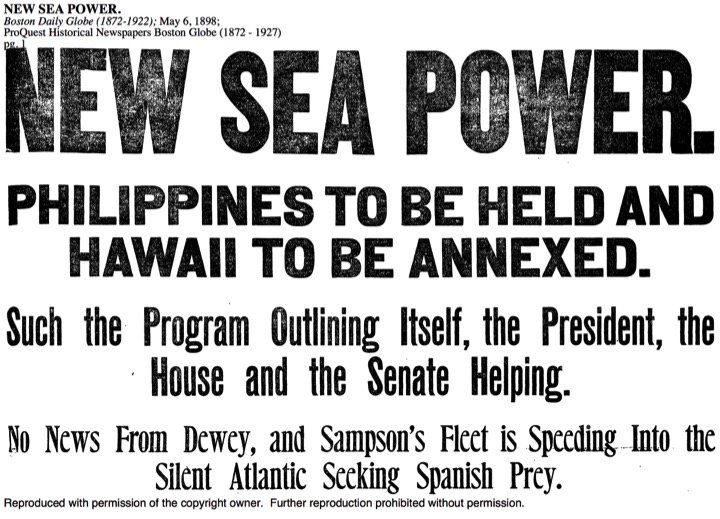

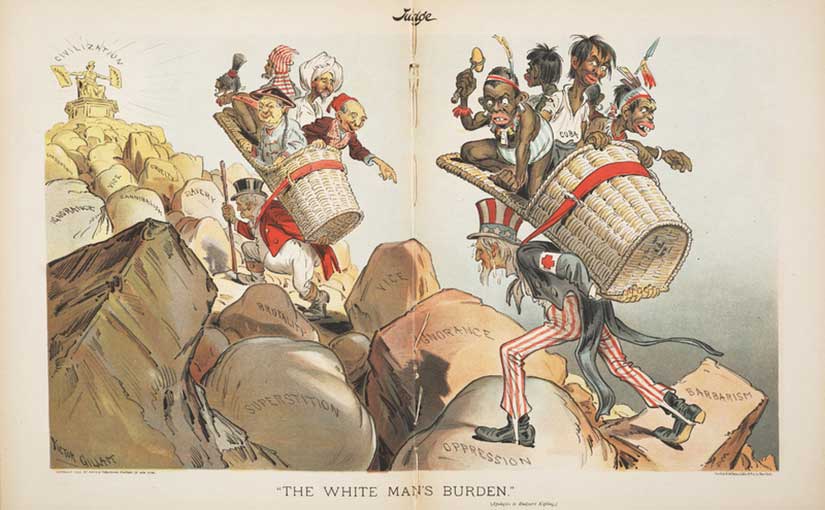

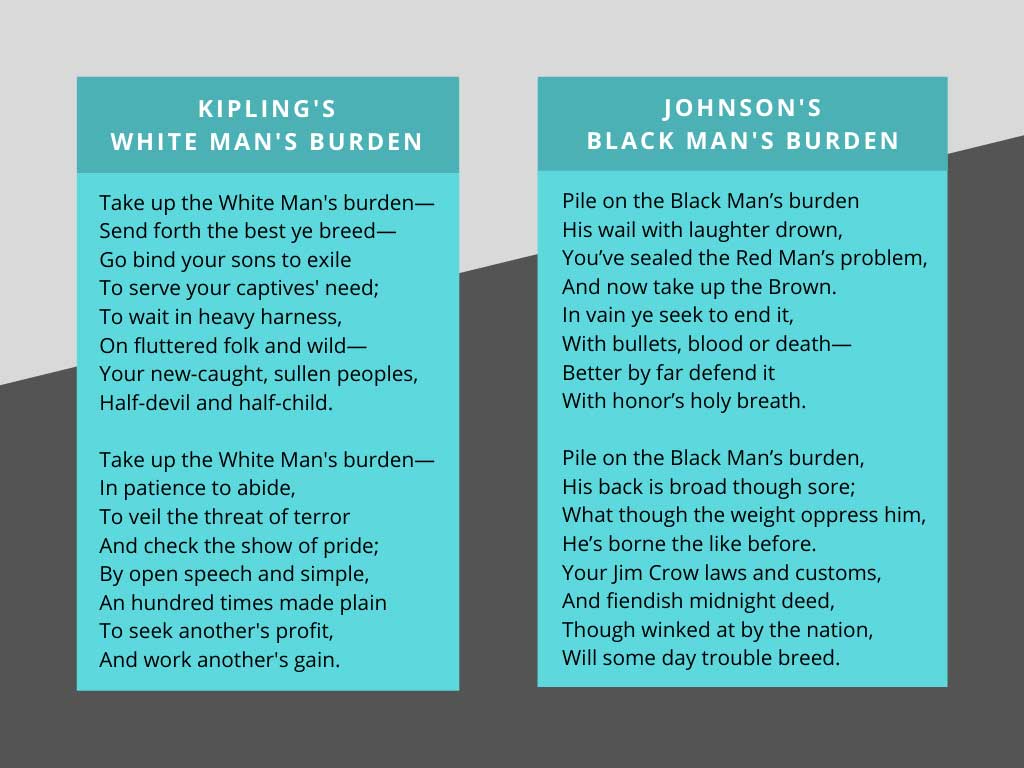

She presents on the history of America in the Philippines: How is a war you have never heard of more important than ever today?

She also presents to writers’ groups on:

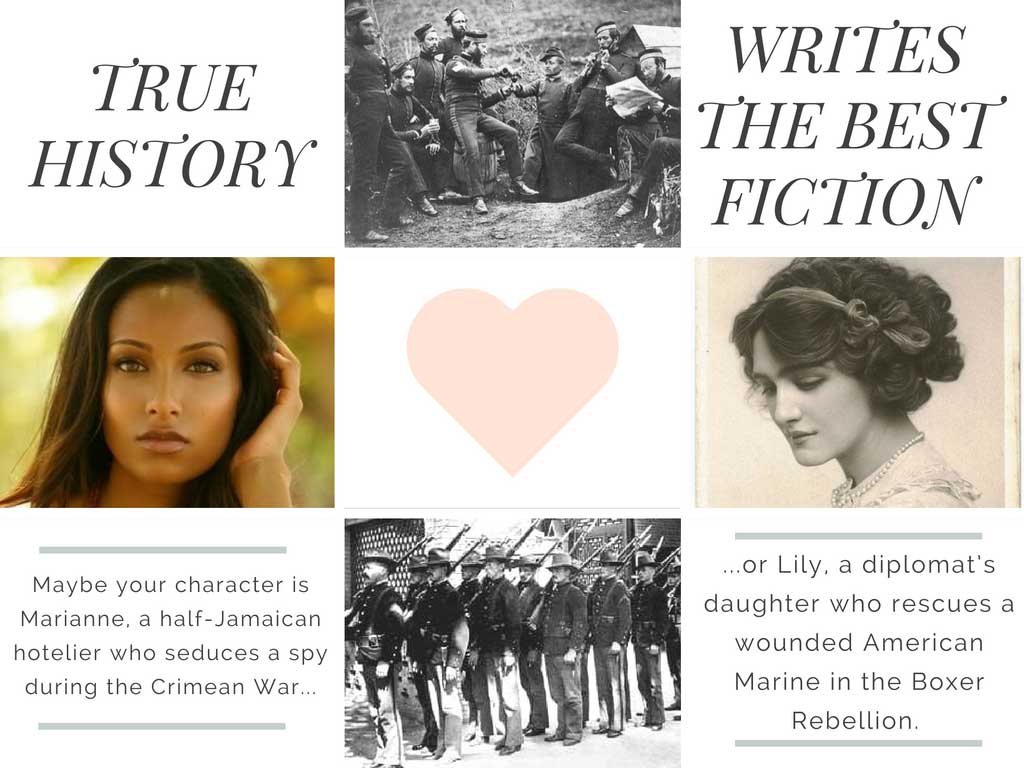

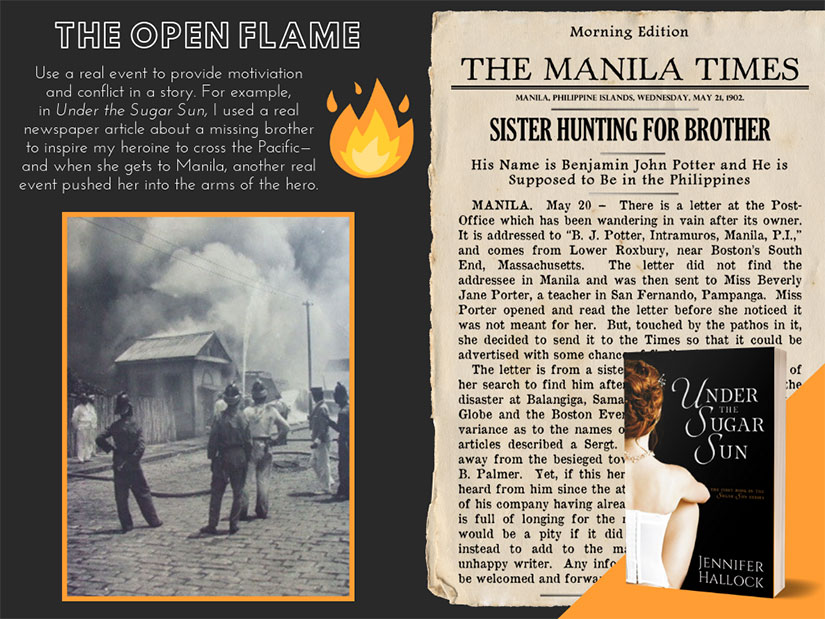

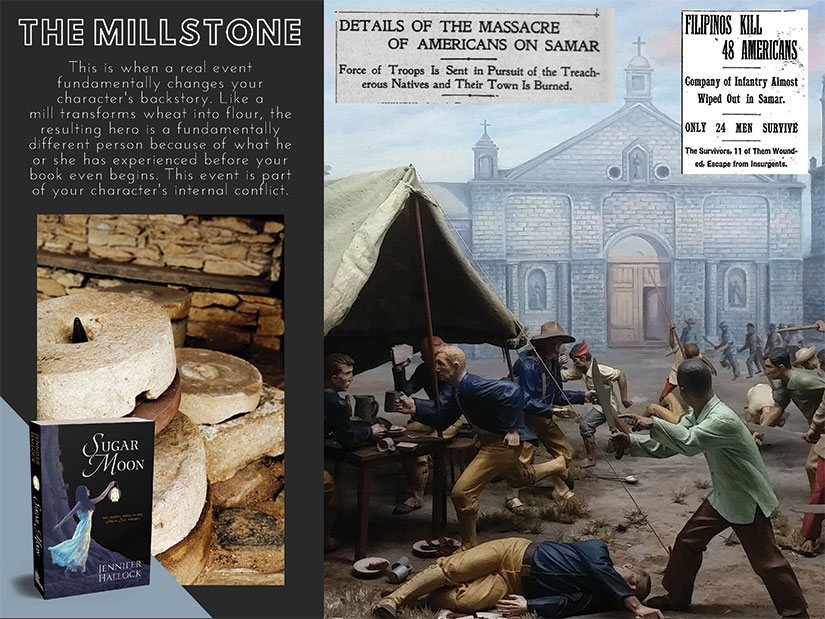

- how to research effectively: The History Games: Using Real Events to Write the Best Fiction in Any Genre

- how to write intimate scenes: Good Sex in Historical Fiction: A Cozy Chat with a Romance Author

- how to use Canva: Can-Do Canva for Writers

- about historical romance chronotopes: History Ever After: Fabricated Historical Chronotopes in Romance Genre Fiction

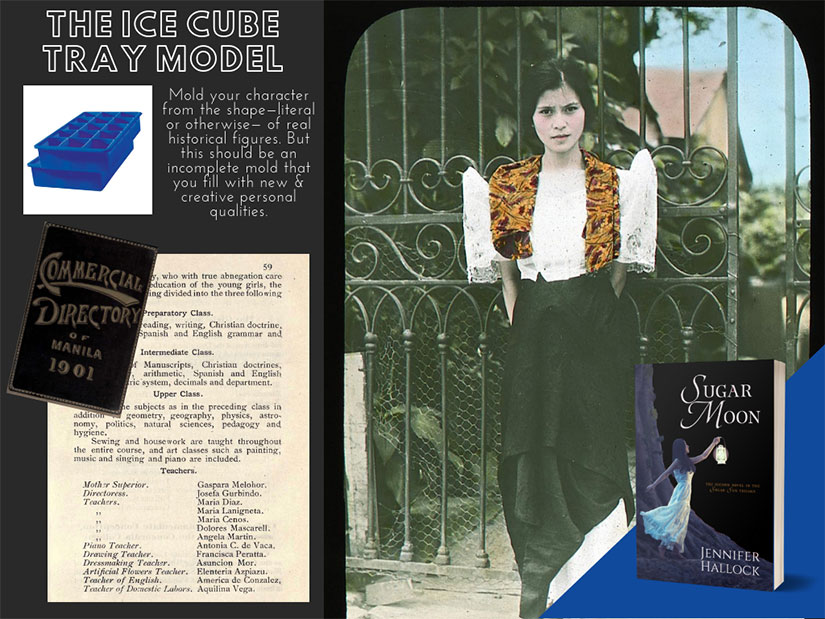

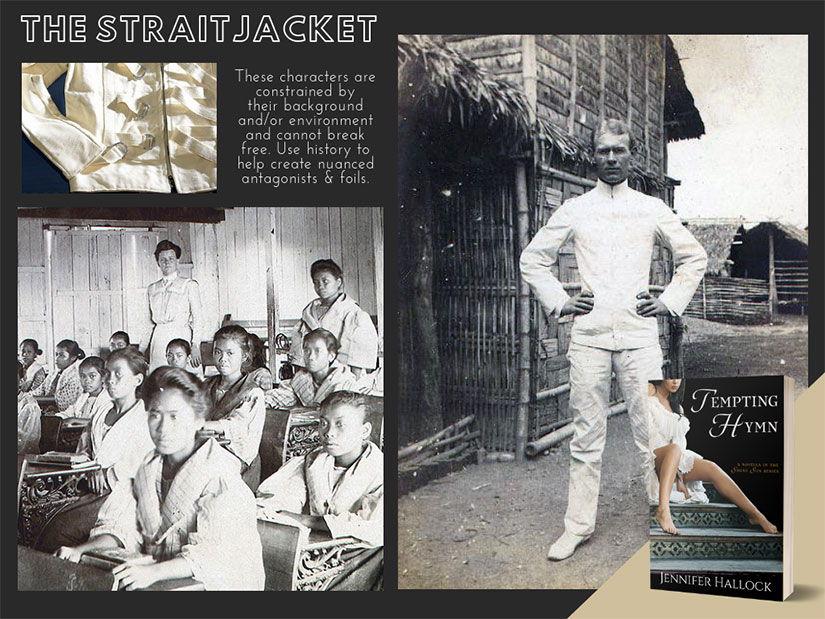

- how to use character and setting tools: The Writer’s Toobox: Character & Setting Tools

Contact Info:

Jennifer Hallock — jen at jenniferhallock dot com

Mailing List — info at jenniferhallock dot com or http://bit.ly/sugarnewsletter

Twitter — @jen_hallock

Facebook — jenniferhallockbooks

Instagram — jen_hallock

Amazon author page — http://bit.ly/jenniferhallock

Photos:

Photos:

Author photo: download here

Sugar Moon cover: download here

Tempting Hymn cover: download here

Under the Sugar Sun cover: download here